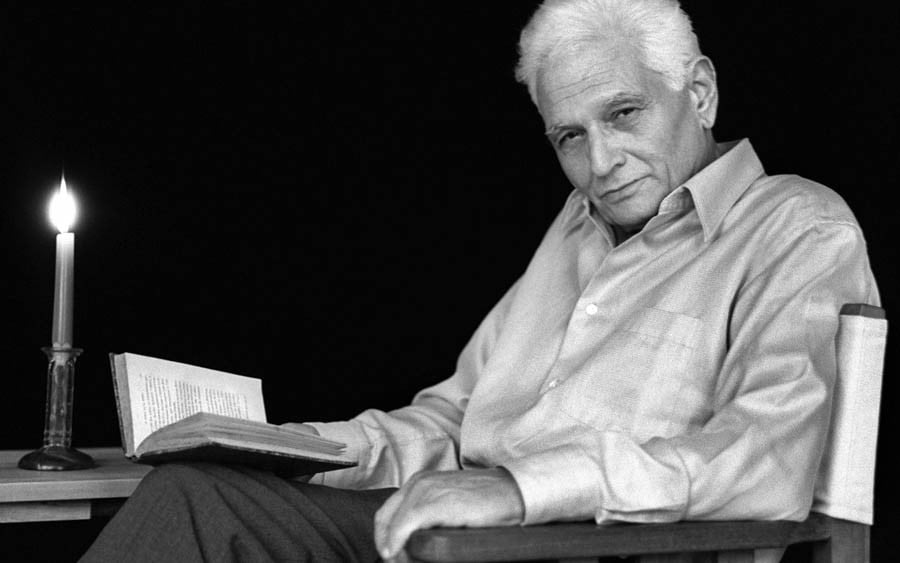

Remembering Jacques Derrida whose ideas were nothing short of a philosophical coup because he challenged and dismantled the metaphysics of Western philosophy since Plato

In France, it was not easy to dislodge Jean Paul Sartre from the iconic position he had acquired in the first half of the 20th century. He was doing the job of intellectual engagé admirably well by operating both on the political and public fronts along with being an avant-garde of his own kind. Riding high on his existentialist angst, he had become so unavoidable an influence that his ideas enriched minds of writers like Ernest Hemingway.

But when Jacques Derrida read his paper, ‘Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of Human Sciences’, at Johns Hopkins University in 1966, he became the new enfant terrible in the Euro-American academies. His ideas were nothing short of a philosophical coup because in one swoop he had challenged and dismantled the metaphysics of Western philosophy since Plato. Pushed aside by his subversive argument, Sartre instantly became anachronistic, though not defunct. The world had entered the times of deconstruction -- Derrida’s destabilising mode of reading the texts.

"On re-/dis-membering Derrida" could be a befitting title for a condolence reference on his death anniversary that fell last week on October 8. As the Beagle Snoopy from the Peanut cartoons once said, when he woke up right under a huge overhanging icicle that had formed overnight on the roof of his doghouse: "I am too me to die," Derrida was too him to die.

One is reminded of his powerful argument in The Death Penalty volumes (collections of his seminars) on how Western philosophy has worked in collusion with the idea that a sovereign state has the right to take a human life and, thus, subscribed to the desire to put an end to the "radical uncertainty of when we will die". This was almost a culmination point of how he countered the position that language is an obedient servant to reason. He fundamentally attacked the way we are ‘present’ to ourselves through language.

Born into an assimilated Jewish family in Algiers, he could never forget the idyllic villa of his childhood days, despite being surrounded by an atmosphere of verbal and physical violence. In 1941 and 1943, he had to drop out of Lycee de Ben Aknoun and Lycee Emile-Maupas because of the hostile anti-Semitic atmosphere. Perhaps he got an awareness of this privileging of centre over margin from his boyhood experiences. No wonder he suggested to prioritise the repressed meaning over the privileged as a fundamental strategy of deconstructive reading and, thus, questioned the centrality of the central in language. He demonstrated his reading method politically by making a personal appearance in Ken MacMillan’s 1982 film Ghost Dance as a sign of his anti-Apartheid stance.

It was interesting when Terry Eagleton said that certain ‘stuffed shirts’ of the University of Cambridge had voted Derrida down for an honorary degree. That is because they had been nourished on essentialist liberal humanist ideas that language could be trusted. But if they could follow Derrida’s Deconstruction, they might well have guessed that his views carried their own potential opposites. And the same was proved when university dons reversed their decision vindicating Derrida’s views that if they thought he was an ‘anarchist’ or a ‘nihilist’, they actually meant otherwise.

Who can ignore the Cretan Paradox and its Albany Solution while reading Derrida. If a Cretan says that all Cretans lie, who would believe that? If he is right, he is lying; if not, he is not a Cretan. Therefore, we need an external authority, someone from Albany or New York, to give an objective and reliable verdict on the Cretans. The crux of deconstructionist philosophy is that language is like a Cretan talking about other Cretans, his own kinsmen. It has no outside perspective. As long as we speak about language and its meanings, we shall be using language, and shall always be the insiders.

In Derridean world, those who think that language is reliable and has unmovable meanings and prejudices, contaminate it with an extraneous perspective. They may variously be labelled as orthodox, foundationalist, or puritanical people whose lives are tied down with strong centres. The socio-religious and anthropological side of Derrida’s views cannot be overlooked because the menace of deconstruction not only created an unlikely interpretive space, but also brought forth the possibility of an ideological vacuum.

Little wonder Derrida is the blue-eyed boy of postmodernists who are all for relativism of truth and fragmentation of reality. Movies like Blade Runner, Blue Velvet and Wings of Desire testify to this nexus between Derrida and postmodernism.

All radicals, rebels, leaders, philosophers, and writers who go against the grain find an implicit recommendation in Derrida’s views. That is why feminists, Marxists, psychoanalysts, and African-American critics have adapted Derrida’s views to advantage. When Lacan revisited Freudian theory and famously wrote that "unconscious is structured like language," it was but an affirmation of Derrida’s essay "Freud and the Scene of Writing" in which he proved that Freud had started thinking of human psyche as a kind of writing -- a script -- a space of writing.

The breadth of Derrida’s concerns is formidable. He expressed views on as diverse fields as philosophy, sexual differences, feminine identity, nationalism, AIDS, media, language, translation and, of course, politics. Thanks to Gayatri Spivak’s inspiring translation of Derrida’s Of Grammatology into English in which he initially builds his point that we must make use of a language that simultaneously uses us -- that speaks through us.

Waltzing down the slippery language ramp, Derrida staged his antics to distraction and became an inexhaustible paradox of our times. He is both sweeping and self-defeating and has earned friends and enemies in almost equal number. Those who take it upon themselves to trash him with language unwittingly do him a favour; those who love him for his radicalism and linguistic iconoclasm wrong him unknowingly -- the reason being that both use language which is not constitutive.

Now, as I write this belated obituary, I am afraid that language is not a reliable medium for condolence. The invisible binary opposites of my feelings keep me from thinking that Derrida has died. His unusual and intricate method of textual analysis would have us believe that as long as he lived, it was actually an effort to die; now, in his death, he is kind of born. All writings to remember Derrida are efforts to forget him.

Jacques Derrida passed away on October 8, 2004