An exhibition at Alhamra Art Gallery Lahore shows works across mediums of ten artists

Ijtima, the name of the exhibition which opened on September 6, alludes to religion being a term usually associated with religious gatherings. The curator, Sundas Azfar, describes the reason for choosing the title Ijtima, an Arabic word, "derived from the word Jama; the opposite of Wahid (means, Singular in English)". She says, the "exhibition ‘Ijtima’, shows works across mediums of ten artists"; and explains the selection of participants: "The presence of one male artist in an otherwise female artist show opens new possibilities of classification and grouping in a social and political domain."

The exhibition that ended on September 9 was all about identities -- religious, national and gender status. The last one includes sexual preference/history, not easily accepted in a conventional society.

Like any good show -- or a normal human being who is not what he/she claims to be -- the exhibition was more than what it stated. Thus one found personal concerns, popular practices, identity issues and formal pursuits all collected under one roof.

One could see subjugated, ridiculed and abused women in the works of some artists. In Huma Mulji’s prints, one comes across a perfect couple; only it is neither perfect nor a couple. Male and female monkeys are photographed as humans with the female dressed as bride and the male monkey standing like a groom for a wedding picture. Referring to gender division or disparity in human society on the one hand, these convey how the humans have tyrannised and terrorised their fellow living beings, on the other.

So, humans who project themselves into their pets or captive animals, in a sense, grant them a substitute role of a human, without the creatures being conscious of this. The identity of a man in contrast to an ape is an important matter because, during colonial times, men from Africa were not treated much differently than what we see in Mulji’s print of monkeys. They were presented as defective versions of a grand human project. Thus, some of them were kept in cages.

Mulji picks that aspect of our popular culture in which a species is trained for a task which is not bestowed to it by nature. Yet mankind tends to enjoy seeing its replicas in other forms. So a male monkey next to a female monkey suggests some clues about domestic settings but in an ironical sense. A viewer is amused by the monkeys playing as substitutes of human relationship -- something which occurs in language too; but Mulji manages to locate, arrange and then photograph these animals which transforms, rather symbolises, human existence in a complex society.

Complexity found another clue in the work of Hurmat ul Ain. Contrary to the meaning of her name, hurmat (honour/sacredness), her work challenges the whole concept -- construct of piety. In a series of photographic prints, a growing up girl is sitting in the lap of an adult man: a relative, acquaintance, a guest or a completely unknown person. The man in the background does not have a face; thus apart from not possessing an identity; he becomes a symbol for all those who indulge in these activities. Ain’s work is not about direct confrontation, but a mere suggestion to a condition in our culture.

A similar kind of suggestion -- or is it proclamation -- was observed in the prints of Abdul Moeez, an artist who deals with the ‘uncomfortable’ issue of same-sex relationships. Yet he succeeds in communicating a difficult content through a subtle scheme. Two men under a veil not only depict an uneasy pose; they also indicate a conditioned mind which is still not prepared to accept how nature has coded different human beings. Though the subject isn’t new or unexpected in the art world, the important aspect of his work is its pictorial quality.

The exhibition was a passage between possibility and impossibility. It is unimaginable to consider a gay couple as legally recognised but it is possible to kill a fellow Muslim belonging to another sect. Lattifa Attai comes from the Hazara community that is subjected to target killing due to their facial features. It must be rare in the world that you bear mark of your religious identity on your face and thus become a quickly identifiable enemy. Attai, understandably, wishes to get rid of her face. So, she camouflages portraits of many who come from the same community with weaves of traditional tapestries (associated with women of Hazara). Each of these works are in the form of photographs for identity cards and passports, documents which are made to reveal your identity; here, they serve an opposite function.

A different kind of identity is explored in the prints of Sakina Akbar in which a little girl is standing next to a large-scale tv remote control. Now that part of the gadget, apart from its phallic connotation, represents the power of a male head of the household who holds the control and decides which channel to watch and for how long. One wonders, if the gadget is about choosing channels or oppressing other family members.

Sarah Mumtaz in her charged lines creates another kind of family that is neither familiar nor friendly. Transformed into the idiom of birds and insects, her work, whether in thread or pencil, suggests the way an artist’s language has the power and potential to excavate meanings underneath the obvious.

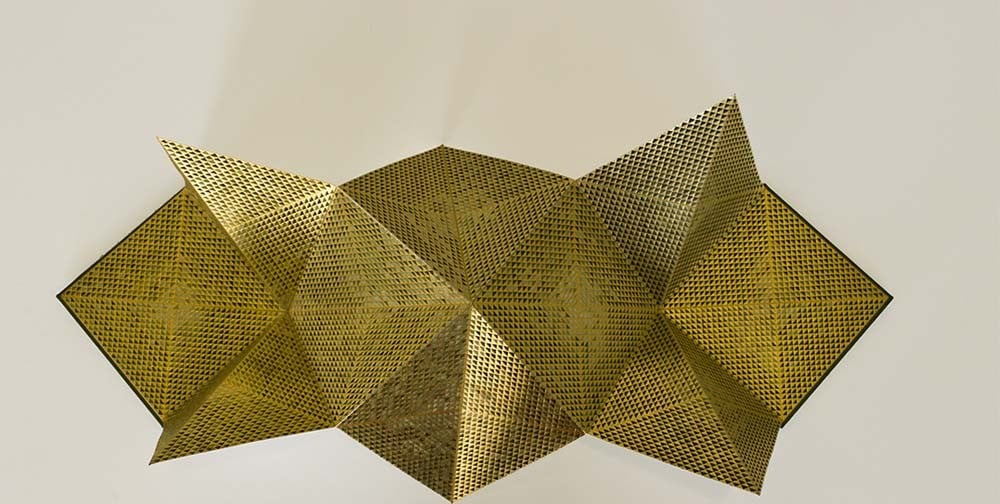

In this collection (ijtima) of art practices, the most convincing art work of our times was by Meher Javed. Shunning the allure/duty of expressing in ‘easily’ identifiable language, the artist constructs a piece with many folds and openings -- all covered with intricate geometry. Small works but the way Javed executes these pieces by concentrating on paint, texture, tone, division of spaces and physical format, these objects, without any political content, are about a visual discourse. Apart from obvious formal and playfulness, it includes and alludes to cultural constructs. In that sense, the work of Javed defies, defeats, and destroys that one-dimensional thinking that one needs to choose a certain imagery in order to convey content about religion, ethics and politics.

Javed’s work is not about one culture or region. It is about art and its impact on senses, beyond borders and periods. Her formal approach reminds one of Roland Barthes: "The author is a man who radically absorbs the world’s why in a how to write."