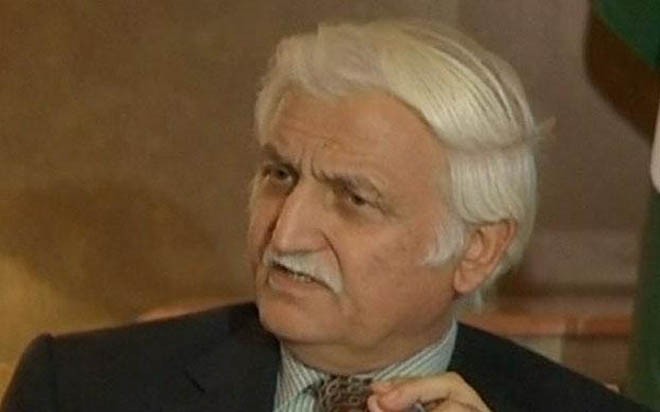

Interview: Farhatullah Babar

Farhatullah Babar, Senator and spokesperson of Pakistan People’s Party chairman and co-chairman, is a prominent human rights activist. In his political career and as member of the Senate, he has been very vocal on human rights violations; laws and policies pertaining to human rights matters. He has always been raising voice on the issue of enforced disappearances in Pakistan. The News on Sunday spoke to him on this important subject, its history, seriousness and challenges. Excerpts follow:

The News on Sunday: The issue of "missing persons" in Pakistan is getting serious by the day. Can you give us a historical overview?

Farhatullah Babar: People disappearing in thin air mysteriously and without a trace was not known widely in Pakistan until General Pervez Musharraf revealed in his memoir, In the Line of Fire that hundreds of militants were caught by Pakistan and secretly handed over to the CIA without trial, without public disclosure. "We have earned bounties totalling millions of dollars," he boasted. This startling disclosure was, however, not made in the subsequent Urdu version, due perhaps to the public storm it had created.

It seems to me that since Musharraf was not held accountable, it encouraged disappearances with impunity by those who thought the legal processes were too tedious to effectively deal with militants. As there was no accountability of Musharraf -- because he was from the military and a sacred cow -- it encouraged the practice to gradually turn into a norm. Apart from militants, political dissidents, human rights activists and those who opposed the state narrative on security policies also started to disappear mysteriously.

TNS: What is the extent of disappearances now with the passage of time?

FB: It is getting too widespread both in terms of geographical areas and reasons for disappearances. Militants alone are not the victims and many other categories have joined the list. This is evident from the figures of the Commission on Enforced Disappearances itself. One may not agree with the figures claimed by Mama Qadeer or by the highly respectable and independent HRCP or by the Defence of Human Rights led by Amina Janjua. But how can one refute the official figures in courts and in the Commission -- which all point towards a steady rise. Secondly, and more alarmingly, not a single perpetrator of the crime has been identified, let alone punished, till date. In some cases, the courts pointed out who the perpetrators were but no one has been brought to book.

TNS: And what makes it so serious in your view?

FB: The phenomenon of missing persons is a case of missing rule of law. Absence of rule of law leads to alienation of the citizen from the state, creates space for the extremists, and destabilises society. Already, the space has been captured by the charity wings of militant organisations. To illustrate, the Senate Committee on Human Rights was recently informed that 51 mutilated bodies were found dumped in Balochistan during the last two years. No relative of the victims lodged any police report. It shows the growing chasm between state and citizen; a manifestation of grave distrust, indeed a lull before the storm.

Horrifying, isn’t it? But is anyone listening? When the courts are not heeded, the parliament is ridiculed and the Commission on Enforced Disappearances short changed, we are sliding down a dangerously slippery road.

TNS: To what extent is it correct that enforced disappearances also take place because of the fragility of legal instruments to deal with hardened criminals?

FB: Absolutely wrong. This is an outlandish assertion. Nothing could be farther from the truth than this. There are anti-terror laws that are not only stringent but also circumvent the procedure. There used to be POPA (Protection of Pakistan Act), remember? There is this ‘Action in Aid of Civil Power’ legislated in 2011 with back-dated effect to enable the security agencies to bring into the open the missing without fear of prosecution. And there are military courts with constitutional legitimacy and back-dated validity. These courts are not constrained by the niceties of fair trial under the Constitution Article 10-A, of fair trial.

TNS: You are also member of Senate’s committee on human rights. Kindly tell us what has the Senate done on this important issue?

FB: It may seem too little to some but the Senate has been playing a very proactive role. Some time back, the Senate Committee on Human Rights examined the issue in depth. It made some half a dozen recommendations, including legislation, signing of international conventions and compensation to the victims. The report of the Committee was adopted by the entire Senate in 2013 but it was not acted upon. In December 2016, the Senate Committee of the Whole made some recommendations on speedy and inexpensive justice. It also proposed a way forward to address the missing persons’ issue.

This is significant forward movement but, unfortunately, it has not been taken forward to its logical conclusion to make the government heed the unanimous Senate recommendations. It would be interesting if any investigative journalist explored, why.

TNS: What more can the Senate do?

FB: Howsoever one may dislike the term "do more," the parliament can really do more. The parliament, not the Senate alone, can and must do much more. First, it should play a proactive role in criminalising enforced disappearances through legislation. It may be recalled that the Committee of the Whole of Senate had asked the government that if it found its recommendations impracticable, then it should revert to the House within 60 days stating reasons. The matter will then be referred to a bi-partisan Committee to decide, it had said.

By taking forward the issue from this point onwards, the parliament indeed will be able to do much more. It might open up a window of opportunity.

Read also: Facing the world

TNS: What do you think about the Judicial Commission on Enforced Disappearances?

FB: Well, it must be acknowledged that the Commission has achieved some modest successes. Its very existence gives a faint hope that the door for securing relief is open. It may be illusory and not real but it is there. Headed by a highly reputable judge, Justice Javed Iqbal, the Commission nonetheless suffers from structural defects as well as performance deficit. The structural defect is: it is not a Judicial Commission, neither is it Commission appointed by the Supreme Court. It is an Inquiry Commission under the executive branch of the Ministry of Interior.

The executive itself is accused of violating human rights and it is an anachronism that such a Commission should be under the executive. It is a body that cannot even make public its report and recommendations. As for performance, it is difficult to rate the Commission very highly. One does not hear much about how far it has carried out its function "to fix responsibility on individuals or organisations responsible for enforced disappearance". Nor does one hear about its performance to get "FIRs registered against those involved directly or indirectly in enforced disappearance".

One is particularly interested in the statements recorded by the Commission, if any, of the missing citizens later recovered that could provide crucial leads but there is not much by way of showing. Reportedly, over one hundred missing persons were kidnapped from within the jurisdiction of the capital territory of Islamabad. Amazingly, there is no word about whether any one official of any security agency was named, let alone questioned. So, these are some of the issues.

TNS: What action, legislative or administrative, is most important to address the issue? For example, which one of the three -- strengthen the commission or legislation to criminalise enforced disappearances or legislation to bring state agencies under the parliament -- is most important?

FB: Legislative measures in all these areas are important. They are interconnected also; legislation in any one will also strengthen the other two. But legislation is one thing and the powerful civil-military bureaucracy implementing it quite another. In March 2013, the parliament made a law forbidding resurrection of banned militant outfits under other names. But militant organisations strut around as charity organisations with the connivance of state agencies.

To peep into the "black hole," we need freedom to speak up. Legislation to protect freedom of expression as guaranteed under Article 19 of the Constitution is crucial. Those freed from captivity are too scared to speak up; they need protection. Giving those protection may help in identifying the culprits and the places of detention. Human rights activists, investigative journalists and bloggers agitating enforced disappearances and others have themselves disappeared without a trace. The case of a lady journalist, Zeenat Shazadi, investigating missing persons who disappeared from Lahore two years ago and the kidnapping recently of bloggers come to mind.

The media is free to lambast politicians, parliament and political parties; but when it comes to such issues, its silence is deafening. It exercises self-restraint. Even when media had footage, it kept on saying that Mullah Mansoor Akhtar had been killed in Zabul because it was thought to be the state’s narrative and, hence, [there was] self-censorship. It was only after the Taliban and president Obama spoke, the media also announced that Mullah Mansoor had indeed been droned inside Balochistan.

So, I would say that legislation to ensure freedom of expression, signing of the international convention [on enforced disappearances] and implementing the recommendations of the UN working group that visited Pakistan in 2012 are most important.

TNS: What concrete steps you think need to be taken to address the issue?

FB: Criminalise enforced disappearances through legislation as Sri Lanka has done. Give the National Commission on Human Rights (NCHR) the autonomy mandated under the law. Instead of being under the executive, the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances should be made into a Judicial Commission. Sign the Convention on Enforced Disappearances, listing also the reservations if any. Set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) as envisaged in the Charter of Democracy (CoD). The TRC is based on the dictum "forgive, but do not forget" and the principle of partial indemnity for full disclosure of truth. Remember, South Africa achieved national cohesion and integrity by overcoming the bitterness of the past. The TRC should include rehabilitation of families of victims of enforced disappearances and acknowledge and honour those victims who were later proved to be innocent.

Furthermore, bring the state agencies under the ambit of legislation. It is not easy though. Several years ago, a question was asked in the Senate "whether there is any law on the statue, and if so to state the law under which the ISI is authorised to conduct raids and detain and interrogate suspects". The startling reply was "this question is of secret and sensitive nature. It asks for information on a matter prejudicial to the integrity and security of the country". So, it is not easy but it is critical to protect the agencies from undue criticism.

Finally, enforced disappearances cannot be separated from the curbs of freedom of expression. The growing misuse of cyber-crime law against social media activists in the name of national security is worrying.

TNS: Can you list some major reasons in order of priority that have led to this situation?

FB: Yes, these are; the aversion of the state agencies to submit themselves to accountability, transparency and parliamentary oversight; pliant and scared politicians too ready to buckle [under pressure] and make compromises; a parliament hesitant to take the bull by the horns and finally a disinterested media that is driven by ratings rather than substantial debate on critical national issue.