In his solo exhibition ‘Laminated Souls’ at O Art Space, Lahore, Imran Hunzai expresses himself in a language that is accessible

A majority of the artists rely on faith in the long and lasting power of visual art that is beyond the limits of newness. Actually, as we examine ourselves we realise we are not unique individuals; we are often a strange refurbished blend of personalities of the past who have left their facial features, genes, habits and even names in the form of new-borns. New-borns may be quite unaware of their distant ancestors; but we all know we are a composition of elements from diverse sources and geographies.

Geography is crucial. Anyone who comes from Hunza, Gilgit or Chitral is not interested to be seen under that ‘locale lens’ because he, like any other inhabitant of Pakistan, expresses in a language that is common, accessible, and appreciated in Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad. Only if you are a ‘concerned citizen’ (or a committed CIA agent) are you going to waste your time unearthing visual constructions that relate to those who live in areas far from the mainstream of political discourse, information and creative expression -- and art. Mainly because when it comes to the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) or tribal areas, one is always trying to think as to what kind of narrative is being projected from there.

In the work of Imran Hunzai, one finds a familiar narrative. One of the eight works on display at his solo exhibition ‘Laminated Souls’ (August 18-31, 2017 at O Art Space, Lahore) depicts the state of Pakistan, particularly its northern region, inflicted with violence. Here manufacturing, possessing, displaying and using weapons were not considered odd acts; instead these were part of the normal course of life. Long before the CIA-sponsored jihad in Afghanistan, weapons were openly displayed in shops and in the public spheres. But, after the international intervention in Afghanistan, our country and KP suffered from the massive spread of arms in our society.

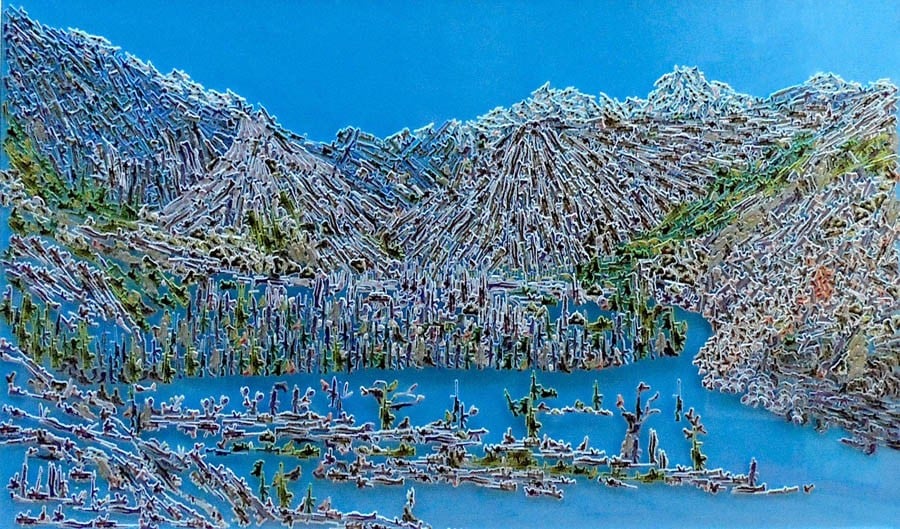

Hunzai has portrayed that situation in a subtle yet strong manner. You see a hilly landscape created on a blue surface (the colour is used for indicating sky and water), with mountains and terrain, which convey the real content. Both are constructed with small stickers, the type you buy at any stationary shop that sells kids’ stuff. But these stickers are of guns of varying models. By making this collage, Hunzai has commented upon and communicated the condition of a region that is associated with violence, as well as being the target of terrorist attacks.

One can locate the source of inspiration in this vocabulary and connect it to the earlier digital prints of Rashid Rana, but Imran Hunzai’s decision to use these slightly raised stickers introduced a three-dimensionality on to the flat surfaces (the artist was trained as a sculptor at NCA).

Another art work called Untitled 1 from the show astonished the viewers for its simplicity of solution and complexity of craft. A similar approach is seen in Untitled 4 in which a tree is composed of guns but, along with weapons, stickers of butterflies, flowers and small birds are added. It is perhaps an attempt to create a contrast or a scenario that encompasses the totality of our existence -- how a culture contains multiple, varying, and warring segments.

However, the inclusion of flowers, butterflies and birds convey more than merely political or social content. These indicate the artist’s preference for a vocabulary -- rather a method or style -- which lead him to fabricate other pieces. In these works, you glimpse a cockerel, a child’s face, another hilly landscape, and a car. He has employed stickers of different sorts -- smiley red lips, emojis, cartoon characters, tiny toys, hearts, animals, and different shapes -- to fill the outlines and forms of his images. In addition to these low relief works, he has displayed two digital prints on canvas with a kid’s face and part of a portrait in high contrast. The former is fabricated with various cartoon characters while the latter is composed of small labels.

Compared to the view of mountains and lake made up of rifles, none others justify the usage of parts to complete the whole. As the works reminds of Rashid Rana, these also make one realise that Rana’s work is not about composing small parts to create a larger picture but small parts conceptually relate to the bigger image. For instance, ordinary people from Lahore who form the icons of Indian film industry. Or billboards which are joined to make the portrait of Mughal Emperor. Or picture of a slaughter-house put together to create a Persian carpet. Or the views of a city that are connected to look like a rural landscape. Most of his recent work reflects the situation of a state/society suffering from the acts of violence, intolerance and terror.

In contrast to Rana’s aesthetics, Hunzai’s work appears more like a stylistic device, without the conceptual strength of Rana.