Karachi is, for the third year running, the world’s sixth-least liveable city according to the Global Liveability Report. But how objective is this report anyway

Muhammad Yunus -- whose name is permanently tattoed on his right forearm, as a relic of a teenage adventure -- laments about the taste of lassi in Karachi and is convinced that the eggs we consume here come from turtles, not chickens: "There simply aren’t enough hens."

A Pakhtun from Jhang, with ancestral roots in Ludhiana, Yunus in his late 50s, says he moved to the city in the 1980s and has largely lived here since. Karachi is where he came after running away from home in the throes of adolescent rebellion. It is also where he found rozi (livelihood), albeit not enough for Yunus to move his entire family to the city. He can’t just bring his wife to Karachi from Jhang either because how would she stay alone at home while he went out to work?

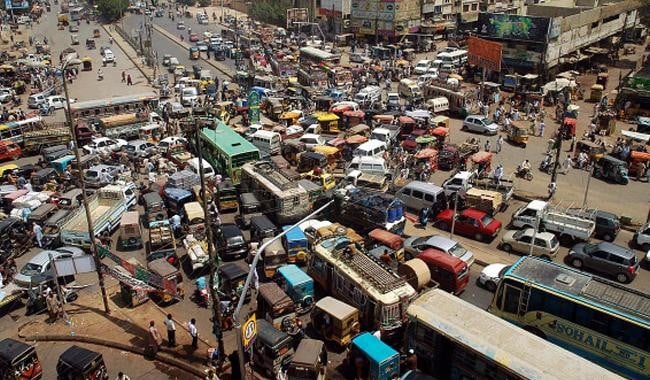

The metrics for good living can be somewhat subjective -- the lassi is rubbish, the eggs dubious -- but, as far as objective analyses go, Karachi is, for the third year running, the world’s sixth-least liveable city according to the Global Liveability Report published each year by The Economist Intelligence Unit. The city’s position on the lower rungs of the list (and many other lists -- see, for instance, Most Polluted Cities) invites the usual handwringing, although it is often forgotten that this particular report is neither a popularity contest, nor a report card. It is a primarily tool for the human resource departments of global companies to adjust salaries according to location. (For those among the globally mobile who deign to live here in Karachi, the EIU recommends a hardship allowance of 20 per cent.)

Indeed, given how much flak Karachi receives, what is more surprising than the low ranking is that it was included in the pool of cities in the first place, the criteria for which is urban and business centres that "people might want to live in or visit."

"The quality of living here is pretty deplorable, be it access to mobility, access to water -- power perhaps is not so bad -- and this is true across most classes, south of the upper middle class," says Gulraiz Khan, an urbanist and a designer based at Karachi’s Habib University. "What has improved is the perception of security, unless of course, you’re not on the state’s best behaviour list."

It is worth noting that, according to reported figures, there were 564 murders in Karachi in 2016 compared to Lahore’s 440. This means that if your baseline for liveability is the likelihood of not getting murdered, then accounting for population, you may statistically be better off in Karachi than in Lahore.

In any case, says Khan, the methodology of the index is worth probing. According to the report, each city receives a rating for over 30 qualitative factors across five broad categories -- stability, healthcare, culture and environment, education, and infrastructure -- with qualitative ratings based on the judgement of "in-house expert country analysts and a field correspondent based in each city". This is what makes it a somewhat subjective exercise after all.

Karachi received its lowest score, predictably, in the stability category -- at par with Tripoli, just above Damascus. Its lowest relative score among the bottom ten, however, is in the culture and environment category, two points below Tripoli.

Khan also points out that an aspect of liveability is "the city’s ability to absorb immigrants"--and in order for it to do so, as Karachi often does, it has to exist in a grey zone of sorts. "If you want a city to be liveable for a large number of people, you have to expect that it’ll be grimy."

Yunus works as a watchman for Jehangir Park, a historic six-acre public space in the heart of Saddar you can see Empress Market at one end, St Andrews Church across the street at the other. Donated to the city by a Parsi philanthropist at the end of the nineteenth century, it served as an important site for political activity in the decades that followed (Liaqat Ali Khan’s mukka speech is said to have taken place there). When Yunus first moved to the city, he used to visit the park: "It was a beautiful place," he says.

Over the years, however, the foliage faded, the little reading room fell into disrepair, and young boys stopped playing cricket in the grass; the government considered converting it into a parking plaza, in a bid to get rid of the addicts who had started congregating there, but the courts halted the plan. It has been rehabilitated as a park now, largely along the lines of its old design -- with the inexplicable addition, however, of mechanical dinosaurs. Other initiatives are sprouting elsewhere in the city, interventions both public and private, which may help bind together what veteran urban planner Arif Hasan says are "four distinct cities".

We will have to wait until next year to see whether or not these efforts make a dent in our official liveability.