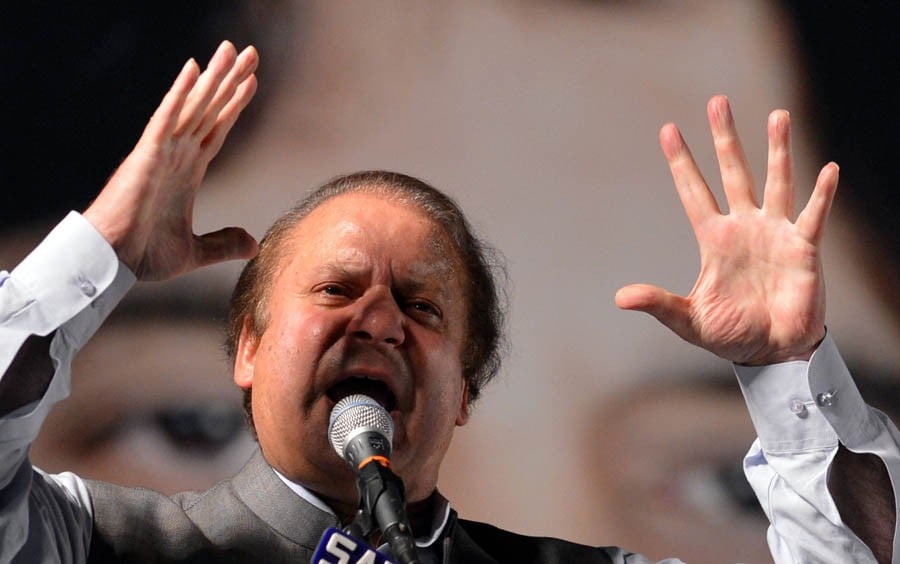

Nawaz’s failure to negotiate political space

The last week’s column ‘The almighty state and politicians’ generated a fierce debate among my colleagues.

The core contention of last week’s column was the structural enormity of the modern state system as it was conceived during the colonial era and the way it has persisted in post-colonial Pakistan. The role of the ‘Establishment’ (read bureaucracy in collusion with the army providing the tight-knit structural base of British imperialism) being the pivotal component in the governance of the state, the politicians had extremely limited space to maneuver.

The limited space in governance available to politicians was entirely up to the sweet will of the civil servants. In the particular case of British Punjab, the army too had a tangible role in the decision-making process at the state level. Thus, legislative, and administrative measures were solely initiated and processed by senior British officers with politicians being content in playing only the role of a second fiddle.

The main critique on the central thrust of my column forces me to dwell a bit more on the issue. The ostensible flaw that was pointed out in the argument pertained to the political space in the post-colonial dispensation, which I argued is almost non-existent. The establishment ought to be defined in the post-colonial context instead of deploying its Western connotation. One of my colleagues detected a fatalism of sorts for the politicians in the post-colonial state where everything was decided by civil servants and army top brass. If that is the case, then politicians are completely absolved of any responsibility as their potential is completely exhausted in their bid to survive against the overdeveloped state structure which obviously is a daunting task in itself.

Therefore, no onus of any sort can be placed on Nawaz Sharif for his failure to deliver on governance as he was caught in the midst of the overdeveloped state and the deep state.

The continuity of the colonial structure in the post-colonial setting could not yield the desired result without severing its connection from the former. The colonial state structure was primarily meant to serve one end -- that was extractive in its intent and not participatory. Such a (extractive) role of the colonial structure could be observed with little variation in the colonial era throughout the contemporary world. The democratic institutions that were introduced in the colonies were not allowed to evolve on the pattern that was employed in Europe, where the loci of power existed. The participatory pattern came in operation very late in the colonial era and could not effectively strike roots. More so, the participatory model was selective and co-optive in its very essence.

In the parlance of contemporary political science, this is called politics of patronage. The local politicians were the recipients of such patronage from the British. The extent of participation accorded to them was circumscribed within the colonial administrator’s will. Thus, it was a ‘controlled participatory model’.

However, according to my colleague Dr. Tahir Jamil, all this theoretical ‘fiddlestick’ actually proves the innocence of the ousted Prime Minister. Of course, he as well as his followers may not be in the know of the state structure and the mutations it underwent with time. That is despite his three stints as prime minister. How can we link the discourse of colonial governance with the disqualification of Nawaz Sharif?

One has to return to the debate of governance and the way it unfolds.

The post-colonial states inherited not only the colonial institutions but also the colonial mindset. The politics of patronage was obsequiously practised not only to secure power but also to sustain it. In the case of Pakistan, the politicians have been found wanting to think beyond a co-optive instrument, which is the legacy of the colonial rule.

From the very outset, the oligarchic system comprising bureaucrats and Army officers took charge of the governance, leaving just a tangential space for the politicians. The way Khawaja Nazimuddin was deposed illustrates the point. When politicians flexed their muscles in 1954, the Constituent Assembly was sent packing. Thus, the politicians were left with no choice but to be content with remaining the second tier of governing structure. Policy-making was squarely carried out by the bureaucracy and what seemed conspicuously lacking was the total disconnect of such policies with the aspirations of the masses.

Things really changed with the arrival of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto as a people’s representative in the 1970s. His was the only era when politicians were comfortably secure at the core of the governance structures. The ‘operation fair play’ orchestrated by Zia ul Haq saw Bhutto off and the politicians were again relegated to marginality.

When elections were held in 1985 and Muhammad Khan Junejo assumed the premiership, it was made quite explicit that the establishment was sharing power with the politicians and not transferring it to them. Elected politicians were not allowed to take any decision on substantive areas like foreign policy and defence. It was in the same year that Nawaz Sharif leapfrogged to political prominence as Punjab’s chief minister. The tenuous relationship between the politicians and the establishment of 1985 persists to this day.

The question that is posed to us is: how can politicians enhance their role in the governing structure. My contention is that it requires the political insight of a true statesman to take charge of the situation. Nawaz Sharif utterly lacks this insight. With limited skill to negotiate with the establishment and hardly any capacity to politically strategise, Nawaz Sharif is hard pressed to carve out a space for the politicians in the state apparatus.

The best way in such circumstances could be, as Professor of Political Science at New York University Bruce Bueno de Mesquita puts it, to deploy a ‘Public Good’ model. This model entails expending resources on projects for the welfare of the maximum number of people. By concentrating on education, the mindset can be changed and by investing in healthcare, greater goodwill among the public can be generated. In its stead, the party in power has squandered resources on projects that we could have done without.

In all those years, our politicians have conceded further space to non-political actors by allowing them to invest in public good, making things even more difficult for their successor(s).

So, to answer the reservations of my critics, the onus for failed governance rests with politician Nawaz Sharif’s inability to sagaciously negotiate space with the establishment. This does not make the state structure more culpable and Nawaz Sharif less to blame for the situation unfolding in front of us.