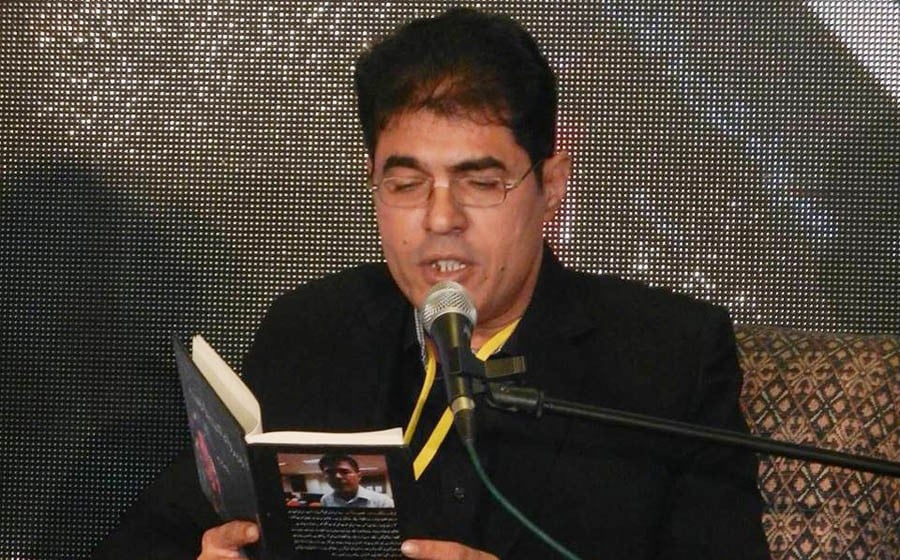

Rafaqat Hayat talks about his novel and trends in Urdu literature

When Rafaqat Hayat’s novel Mir Wah ki Raateen first appeared in a magazine, it created ripples in the literary circle for its bold subject, sensitive portrayal of the character, innovative language and realistic depiction of life in a small, dusty town. The novel was later published separately in a book and since then it has won the admiration of critics and readers alike. Here, The News on Sunday talks to Rafaqat Hayat about his novel, trends in Urdu literature and his future works. Excerpts follow:

The News on Sunday (TNS): Your novel Mir Wah ki Raateen explores themes considered taboo in our society. Do you think our society is becoming more open in accepting these themes?

Rafaqat Hayat (RH): My novel is not a tool to measure the openness of the society. It is a fact that our society is stuck in the quagmire of moral shallowness and creative mediocrity. In this situation, this small existential and psychological novel about sex and other taboo subjects cannot be widely accepted. But, we must acknowledge that these topics are now no longer considered indecent or shocking. A lot of fiction has been written on these topics. Manto and Ismat Chughtai wrote marvellous stories on these topics. I also want to mention the novel Garge-e-Shab written by Ikramullah about incest. The authorities of the time called him then about making an indirect reference to martial law. Sex is treated with seriousness in many genres of Urdu literature. But it requires creative maturity and literary honesty to write, as well as to read, on the topic.

TNS: How was the critics and readers’ response to your novel?

RH: There has been mixed reception to my novel. Some have praised it while others have censured it. When the novel was first published in quarterly magazine Aaj, I received many opinions --- some were surprising, others encouraging. Later it was published as a novel and as far as the literati are concerned, they praised it. Tanveer Anjum, the famous poet, commented that although the novel is anti-feminist, she felt sympathy with the male protagonist of the novel who undergoes the same existential agony as the female characters do. Similarly, Mohammed Hanif, the famous novelist, also praised it.

The criticism it received was on moral grounds, rather than literary. Some felt that the novel violates familial relationships which we highly revere in our society. Others felt that the novel tarnished the image of Sindh. I have listened to all kinds of criticism and am thankful to the critics.

TNS: Critics say that your female protagonists serve merely as vehicles that receive the male protagonist’s frustration. How would you respond to that?

RH: In our society women are objectified and seen as sex tools even in the protected precincts of their homes. This status of women reveals that our cultural and spiritual claims are shallow. In small towns and villages, women are compelled to live lives which are imposed on them by their men who treat them like chattel.

I don’t think women are objectified in my novel. Both my female characters are victims of social injustice because they are deprived of the right to live on their own. But they yearn for fulfilment of their suppressed desires. The protagonist of the novel has had a relationship with both female characters on their own free will. Both female characters use their secret freedom to fulfil their unfulfilled desires.

TNS: There is fusion of Sindhi and Urdu in your novel. Do you think that Urdu is now coming out of its urban image?

RH: Urdu has long been dispelling the impression of being the language of only cities. In Urdu literature, we can find numerous examples of the use of idiom of villages. In Urdu fiction, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Balwant Singh, Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi have mastered the art of using Punjabi words in their stories. Similarly, Manto and Krishan Chander employed various dialects of Mumbai to delineate diversified characters in their stories. In poetry, even in a delicate genre like the ghazal, Zafar Iqbal has used Punjabi thus liberating Urdu from the influence of old Dehlvi or Lakhanvi dialects.

Similarly, Hasan Manzar and Asif Farrukhi employed the fusion of Sindhi and Urdu in their fiction. One can find such examples in poetry as well. Hasan Manzar has beautifully depicted the rural life of Sindh in his novel Dhani Bux Kay Baitay. Muhammad Khalid Akhtar’s truthful depiction of early life of Karachi in his novel Chakiwara Mein Visaal and in his other stories is still worthwhile. But, in spite of all these examples, I believe that Urdu needs to develop its relationship with other languages so that this estrangement between Urdu and other languages may end. In my novel Mir Wah ki Raateen using a few pure Sindhi words was necessary to synchronise the setting, narrative of the story and the characters.

TNS: How have your earlier life experiences shaped your writings, especially your novel?

RH: My grandfather was from Chakwal in Punjab and he migrated to the Khairpur district of Sindh as an agriculturalist. My father also shifted here after his matriculation and spent some time in Thari Mir Wah in Khairpur District. Later he shifted to Mehrabpur, that’s where my three brothers and I were born.

I spent my childhood in various towns of interior Sindh including Nawabshah and Thatta where I received my early education. When I was studying in my first or second standard, I started reading small colourful story books, mostly fairy tales, which I bought from bookshops for four or eight aanas. As I grew up, I started reading detective and romantic literature published in digests. It was much later that I began reading serious literature.

In 1995, I got a job in the telephone department and went to Sukkur for training. It was during this phase that I started writing short stories, some of which were published in Mah-e-Nau and other literary magazines. While reading Chehkov and Marquez, I always felt the locale of their fiction was similar to the locale of interior Sindh. That encouraged me to start observing the interior of Sindh and write stories about the lives of the people of these areas. I used to send my stories to M. Salim-ur-Rahman, editor of Savera and an established writer, who advised me to write novels. In 1999, I wrote the first draft of Mir Wah ki Raateen, after reworking it into a second draft, I asked a few friends to read it and give me feedback. Some asked me to take out entire chunks, but I didn’t listen to the advice.

TNS: Tell us about writers who greatly inspired you?

RH: I can’t say anything about the affect literary figures had on my prose. This can better be told by my readers and critics. Nevertheless, I continue to be fascinated by many writers including Manto and Bedi.

TNS: Who are some new writers redefining Urdu fiction?

RH: It would be impossible for me to take the names of all those who write Urdu prose these days. Syed Muhammad Ashraf’s novel Akhari Sawarian, which is recently published is a wonderful novel. Khalid Javed’s novels Maut ki Kitab and Nemat Khana are also very important. A French writer Julien Columeau has written some marvellous novelettes and short stories in Urdu. Ali Akber Natiq has established himself in a very short time. Abrar Mujeeb, Iqbal Khursheed and Muhammad Abbas also write well. There are lots of expectations from Jameel Abbasi and Zaki Naqvi. Syed Kashif Raza has completed his novel which will be the next experiment in Urdu fiction.

TNS: Many writers of Urdu and other languages find literary spaces dominated by writers of English fiction? Do you think this is true?

RH: The readership of Pakistani writers of English is mostly based abroad. Most of these writers focus on the markets of Europe and other countries and the awards that are given there. These writers have a greater effect outside the country than inside. Even in our literature festivals, writers of English are given priority over writers of Urdu and other languages.

If the basic issue of publication and distribution of books written in Urdu and other languages is solved and the writers receive royalties, then the situation can be improved. We must overcome the monopoly of publishers, government organisations and literature festivals. We also need an increase in serious readership to solve the problem.

TNS: Some writers complain that electronic and social media is encroaching on the space once occupied by print media, especially books and literature. What is your take on it?

RH: I don’t agree that social or electronic media have caused any damage to literature or book reading. On the contrary, social media has fostered the increasing trend of book reading and book buying. Social media has become a platform to promote Urdu literature. Many poets publish their new creations on Facebook. However, what is being shown on electronic media is sure waste of time. It is better to read a book instead.

TNS: Your novel is also serialised in a web magazine. How do you see the growth of cyber space for those voices which didn’t find place in the traditional print magazine?

RH: Internet or social media cannot replace books, they can all work together. Mir Wah Ki Rateen was serialised on a web magazine called Laltain, it also appeared on three other websites. The purpose of publishing on websites was to reach more readers and this was achieved. There are some very good magazines on internet. Almost all important names of Urdu literature are published on these web magazines. I think it is an encouraging sign.

TNS: You also write serials for TV channels. How do you balance your creative urges and your professional needs?

RH: Yes, I write scripts for various TV channels and production houses. Writing fiction and writing for television are two entirely different things. While writing for television, one has to consider the demands of the market, producers and production houses. The writer’s freedom totally vanishes in such situation. While writing fiction, I feel myself riding on a horse whose reins are in my hands. As I am working for a TV channels nowadays, there is little time left for my creative writing. My speed of fiction writing has slowed down.

TNS: There are rumours that you are writing another novel. Can you tell us what this novel is about?

RH: After Mir Wah Ki Rateen there is a long novel set in Thatta and its adjoining areas. I have written its first draft, but I have yet to finalise it. Let us see when I’ll get time to complete it. Moreover, I have started another novel set in Sukkur and Badhah town in Larkana District. This novel comprises five or six parts. I am almost done with the first part. Again, let us see when I’ll be able to complete it.