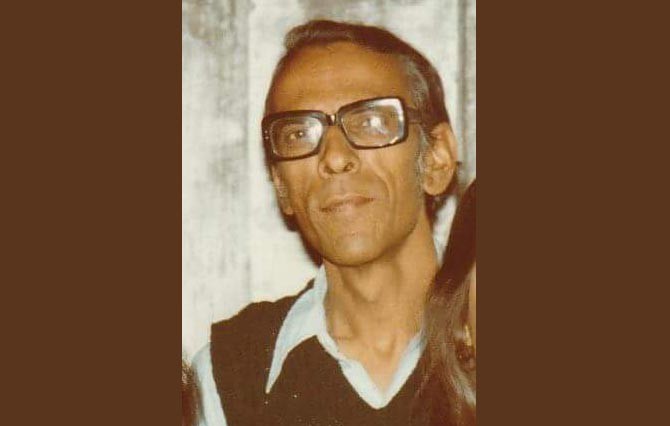

Naiyer Masud, the foremost short story writer of Urdu, is matchless in the underlying absurd, bizarre, paradoxical happenings that are suppressed in logical discourses about humanity. His death is a colossal loss to Urdu fiction

Naiyer Masud passed away on July 24 in Lucknow after remaining ill for a few years. It is true that Maot Say Kis Ko Rustagari Hae (Nobody can escape death), but the news came as dreadful tidings for Urdu readers. It has been rightly taken as the second colossal loss to Urdu fiction after Intizar Husain, though both had less in common except greatness.

Born in 1936 in Lucknow, Naiyer Masud was a scholar and short story writer. Though he taught Persian at the Lucknow University; did research on Dastan and Marsia and wrote critical and biographical accounts of Anis, Yagana and Ghalib, his outstanding fame hinges on his short fiction. There is one more intriguing contrast: almost all his scholarly works revolve, more or less, around reclaiming cultural and literary peculiarities of Oudh and Lucknow, but his four slim collections of stories set a shockingly new, almost inimitable, tradition in Urdu.

Seemia (The Occult), Itr-e-Kafoor (Essence of Camphor), Ta’oos Chaman ki Maina (The Myna of Peacock Garden) and Ganjafa (Card), his four books, contain only thirty four stories. Sang- e- Meel has published Majmooa Naiyer Masud, excluding his last collection, Ganjafa. Masud had also translated a few short pieces of Kafka and some Persian stories into Urdu.

Naiyer Masud read Kafka carefully; translated him skilfully but stayed away from following him. Only heroes are zealously followed. He didn’t take Kafka -- or any other writer, Eastern or Western -- as a hero. The truth is that Kafka and Masud’s fiction ardently put the very existence of hero and its symbolic dispensations, including grand ideas or glorious past traditions, into question.

In reality, Kafka is the precursor of Naiyer Masud in the sense that Jorge Luis Borges once described in his short essay ‘Kafka and his Precursors’. Borges mentions Zeno’s paradox against movement: "A moving object at A (declares Aristotle) cannot reach point B, because it must first cover half the distance between two points, and before that, half of the half, and before that, half of the half of the half, and so on to infinity’’. That infinity with incessant indecisiveness forms the infrastructure of Kafka and Naiyer Masud alike.

In ‘Sasan-e-Panjum’, a short story included in Itr-e-Kafoor, Masud has tried Zeno’s paradox against movement by saying, "without predecessor four Sasans, the existence of fifth Sasan cannot be established and in history except one Sasan, there are not mentioned Sasan Second, Sasan Third and Sasan Fourth. Therefore it might be inferred that Sasan Fifth too didn’t exist’’. The reader cannot help but being trapped in such linguistic maze.

Borges also refers to "Léon Bloy’s Histoires désobligeantes and relates the case of some people who possess all manner of globes, atlases, railroad guides and trunks, but who die without ever having managed to leave their home town’’. We find similar people in ‘Seemia’, ‘Maskan’, ‘Nudab’, ‘Itr-e-Kafoor’, ‘Ihram ka Meer Mahasib’, ‘Sultan Muzzaffar ka Waqia Nawees’ and ‘Nosh Daru’. They are people of fiction defying almost all ordinary rules of real world. They resemble less with the people -- as far as their dreams, wishes, intentions and patterns of thinking are concerned -- we come across in daily life or with the characters we find in books of history; they are highly inventively fictional, but, of course, not fictitious.

Though real world lurks at the margins of his fiction, the central place has been occupied by illusions, mazes and linguistic paradoxes. Ironically, these fictional characters make us think forcefully about the underlying absurd, bizarre, paradoxical happenings and realities that are suppressed or couldn’t have found room in logical discourses about humanity. In this, Naiyer Masud is matchless. Majority of fiction writers depict suppressed and marginalised absurdities in realistic or surrealistic mode, but his illusory texts predispose us to these absurdities.

Some critics are of the view that Masud’s stories just create a ‘delightful illusion’ that evades meaning. It needs to be stressed that nothing is meaningless either in his fiction or in the world. Even the state of meaninglessness has to be captured in some sort of meaningful way. Certainly, his stories are illusory but their illusion is permeated with multilayered meanings. He creates illusion by employing a particular narrative technique of saying less. His fictional world is abundant in ‘absence’, ‘untold’, ‘unvoiced’ and ‘unsaid’. The meanings of his stories are revealed more in untold and unsaid spheres which are created by stretching language to its limits.

Naiyer Masud’s stories defy rules, technique and conventions of realism and surrealism alike. Both explicit social realism and unequivocal psychological realism haven’t even been tested in his fiction. Instead of representing the logical outer world or inner dreamy world of persons, his stories keep referring to themselves, to their illusive motifs. In order to fully realise the magic of his stories one has to keenly follow every sentence, each word and all empty spaces and dots and their relations to the text. Nothing is superfluous in his stories.

In his fiction a kind of autonomy of text is ascertained. The real magic of his stories lies in this: an autonomous, self- referential text possesses the power of destabilising "normally logical concepts" of reality.

These lines from ‘Seemia’, undoubtedly his best, describe how a ‘language play’ can strike at the foundations of ‘normal logical thinking’ into grasping the grotesque of reality. The central character of ‘Seemia’ and his malik (master), both living in a devastated palace, conjecture that the devastation was not caused by time or accident but it might be ingrained into the essence of ‘being’ of the palace. The relation between preservation and devastation is not causal or a sort of one-after-another kind. Both exist in and at the same time, perhaps without establishing any kind of hierarchy.

In most of his stories, the opposites are dissolved; boundaries of now and then, here and there, real and unreal, cause and effect are distorted and blurred. A state of metaphysicality emerges. The illusion of his fiction begins to signify the ‘performance’ of metaphysical ‘being’. The meanings of metaphysical being cannot be grasped in ordinary rational dictum but they can be interpreted symbolically.

Read also: A mysterious autonomy

His stories are not ‘symbolic’ in the general sense but they carry a lot of symbolic meanings. Most critics like to relish the illusory, indecisive elements of his fiction. But this is the first step to enter into the mysterious world of his fiction. His fictional illusion is not hollow from within, mesmerizing only for a brief period of time. Nor is it filled with poetic metaphors or images that spur our hermeneutic faculty. It is a myth of its kind, pregnant with symbolic significance.

Contrary to the generally held view, his fiction is not altogether apolitical. It is the perspective of reading that has skipped the political aspects or connotations of his few texts. He wrote more on ruined buildings, gardens and abandoned arts. It has implicit political implications. Likewise, his story ‘Ihram ka Meer Mahasib’ (Chief Accountant of the Pyramid) is replete with political significance. It narrates how the Pharaoh and Caliph go hand-in-hand and how the Caliph’s chief accountant manages account digits to do what the Caliph wished to have him do. ‘Sultan Muzzaffar ka Waqia Nawees’ also reveals the politics of historiography.

In life, Masud has been widely read, eagerly translated and passionately appreciated but less interpreted, particularly by Urdu critics. Hopefully, an era of his critical study will begin soon.