Instep opinion

Putting together a memorable fashion shoot is not a process as leisurely as flipping through the magazine it finally appears in. Pretty and typical pictures can get super boring super-fast, so the best fashion shoots are those that are engaging and compelling, requiring talent and hard work, innovation and ideas. They also require an understanding of global sensitivities and cultures because fashion does not and cannot thrive in a bubble of its own.

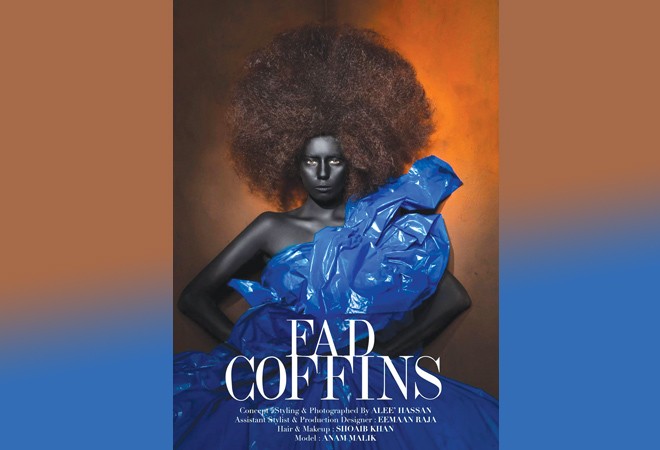

LSA winner Alee Hasan’s ‘Fad Coffin’ marks the latest in an unfortunately long line of shoots appropriating blackface (more on that later) for "edgy" shoots. This is an editorial that appeared on his official Facebook page this week and it was offensive for so many reasons. The model and his muse, Anam Malik has her face painted black with her hair left wild and unkempt, like in an afro. The title reads ‘Fad Coffin’ and has her dressed in what seems like a trash bag. When reached for comment, Hasan said he failed to see why people found it offensive and that there was research behind the editorial which he would share; he was unable to explain his point of view at the time this article was written.

‘Fad coffin’ could have been an interesting concept because fashion is so cyclical and trends come and go. However, this editorial took an awry creative direction. It points out the team’s blatant ignorance to historical precedence and how we understand race and cultural sensitivities today. Blackness isn’t a caricature for people to wear and remove as they see fit, no matter whether it’s for a Halloween party in America or for an "artistic editorial" in Pakistan.

By now, most of us have come to understand how appropriating a culture means extracting elements and aspects from marginalized groups and benefiting from them and how it can be made acceptable (inclusion of said people). Regardless of where you sit on the cultural appropriation vs appreciation debate, the take away lesson is to acknowledge that for culturally diverse people, blackface like Anam’s in the editorial is about more than just a captivating image. It’s a part of their history, community, identity and language. It might be made from makeup and clothing, but it’s so much more than a "look".

Some argue that fashion is an art and artists reserve the right to artistic expression. Others argue that the use of blackface is not simply for artistic purposes but rather is a racist and offensive act that perpetuates longtime stereotypes of African-Americans. Blackface has a longstanding history – it was a theatrical make-up technique popularized in the early 19th century as a form of entertainment where they would paint their faces using burned bottle corks mixed with grease paint or shoe polish. This costume served to exaggerate African-American appearance in a caricatured way and stereotyped them as dim-witted and buffoonish. It was a popular form of entertainment in Europe until World War 1, after which it died off although some people continued to make use of it in vaudeville, film and television. Today, colouring your skin darker is considered blackface because of the offensive connotations associated with it. Golliwogs, for example, were discontinued decades ago for their racial referencing. Knowing the history of blackface and the negativity around it, it should be logically assumed that it is simply not okay to purposely darken your skin or someone else’s.

In the fashion industry, where shock value is everything, it seems only logical to introduce a dose of controversy and this isn’t the first shoot that’s offended people. Last year at the Magnum Party a dark-skinned Pakistani was hired for its chocolate tub in a bid to create ‘surrealist art’. In 2013, designer Amna Aqeel published her Be My Slave fashion shoot in a local magazine. The shoot featured a model being waited on by a dark-skinned child. Two years ago, Ali Xeeshan also darkened the skin colour of his models for a bridal shoot, where he claimed he wanted to tell people that their skin colour is the right colour but people wondered why he simply didn’t use models of darker skin colour? This perpetuated the idea that dark skin is okay as long as it is on for the sake of a shoot for effect. This practice gives the impression that fair skin is preferable and superior to dark skin and girls with fair skin have better chances of ending up on the cover of magazines. This embodies and perpetuates the same ideas from the caricatures of blackface performers in the early beginnings of minstrelsy shows.

An important question to ask in the case of the photographers that used fair models and darkened their skin is, why not just use actual black models? Although not available in Pakistan, a black model is not difficult to find for a photographer of Hasan’s calibre. He could easily travel to where he could locate one and shoot with her, had the inclusion of those features been that integral to the shoot. The editorial concept could have been well-intentioned but remains fatally flawed in a global communications environment; an environment where Sudanese model, dubbed Queen of the Dark, who’s become an Instagram sensation and is encouraging black women to love their skin.

We often neglect the underlying problematic images in our everyday lives and such recurrent imagery only serves to normalize racial discrimination so it’s important to speak against them. There are some taboos even fashion shouldn’t break not even for "art".