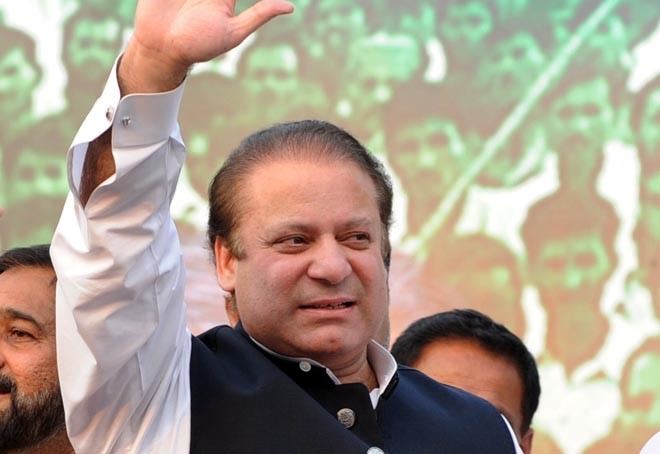

For the Sharifs to be at their pinnacle requires that Nawaz Sharif continues to compete for power, else the clients will shift their loyalties risking the implosion of the PML-N

Panama papers have taken a huge toll on the Pakistani nation because it has dominated the discourse for months on end at the expense of critical policy issues such as extremism, underemployment, population explosion, environmental degradation, education, and rising inequality, to name a few.

Thus, it is imperative for every leader to try to put it to rest, as should Prime Minister Sharif, especially after a damning investigation report. So why is the prime minister not stepping down at the expense of his face or popularity?

The Sharifs have been outstanding political players even after their break from the military establishment in the 1990s, and thus this current strategy to fight till the end must be well thought out. To make sense of this strategy, one has to understand the political ethos of our larger reality where access to state is key to political survival rather than ideology or ideals.

To put it plainly, a village Chaudhry will continue his reign despite rape and pillage, primarily because of his unchallenged power. He will lose his power the moment he apologises, leaves his position or is brought down. Though the village knows about his murders, and murmurs are abound, no one dares cross him because his power is boundless -- the numberdar, police, courts, administration are all bound to obey him.

No wonder in electoral terms, where majority of the population counts, little has changed even with the JIT decision.

For the vast subaltern client population, survival in our lawless jungle requires a powerful patron, because the Pakistani state rather than securing citizen rights and providing services, is more adept at revenue extraction for state functionaries. The strength of the Sharifs has been to incorporate this traditionally rural patron-client structure within the urban landscape of Punjab.

Therefore, the PML-N is relatively immune to ideological or popular challenges because of the party’s 30-year entrenchment of the patron-client network that reaches the grassroots and its adeptness in subsuming new upwardly mobile patrons thrown up by society. While it has a relatively small group of active supporters who have been direct beneficiaries, more importantly, its political adversaries in Punjab have been brought over because they could not sustain being on the wrong side of the state, while only a few survive with the energy to compete.

The PML-N’s strength can be gauged by the strength of its original backers, the traders who are well organised and have profited enormously by staying undocumented and outside the tax net, while the last local government elections suggest real estate brokers as the new important addition to the party. These new patrons bring with them new clients, and get adjusted in a multilevel network with the Sharifs at the top. In return, they not only get safeguards from the state to strengthen their existing societal position but also access to state machinery for further enhancing their own power and wealth.

To be fair, all PMLs have the same patron-client based DNA, the PPP started moving towards a patron-client structure soon after Bhutto kicked out the ideological segment while the PTI has also been increasingly incorporating the ‘Electables’, in our term, the patrons with their own client network.

Hence, the premier’s decision to not resign has to be assessed within the above described political landscape because stepping down from power has huge risks. First, Sharif losing power would break the psychological hold of being powerful and, thus, above accountability, primarily because this would be perceived as the doing of a political adversary, and not the all-powerful army.

This could force a rethinking by the subaltern to change their patron and by the tamed bureaucracy of their personal loyalty. Still with the Punjab government intact, this may not be as dangerous to the Sharifs as having to put a client in power, who could cultivate his own client base for almost a year before the next elections.

Having been ‘betrayed’ before by those with their own independent base (Pervez Elahi) or by smooth operators wanting to cultivate their own (Chaudhry Sarwar), Sharifs do not want to take the risk. Their insecurity about leadership within their own party can be judged by their choice of president, an uninspiring figure; the governor of Sindh who passed away within months of being appointed; the complete disregard for local governments, and the lack of powers of those elected to represent their constituencies; and, lastly, running the state primarily through the bureaucracy.

However, to keep it within the family, Hamza Shahbaz has to be acceptable for the Sharifs.

In an immature democratic system, with a poor, rights-less electorate, the patron-client network is self-sustaining. But for the Sharifs to be at their pinnacle requires that Nawaz Sharif continues to compete for power, else the clients will shift their loyalties risking the implosion of the PML-N.