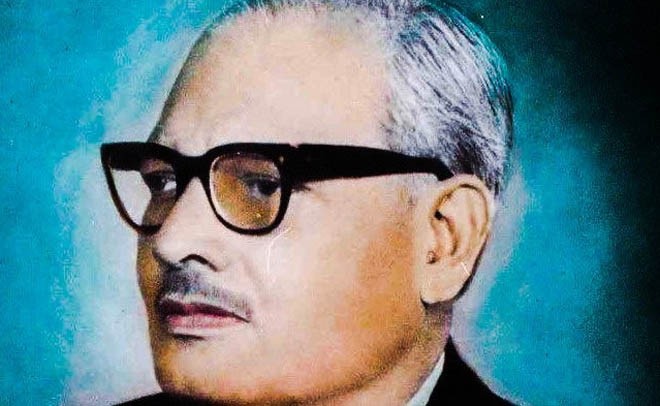

The life and career of Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi

It might seem reductionist and terribly facile to assert that in Pakistan the general historical sensibility predicates on the ideas of three personalities: Shibli Nomani (1857-1914); Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi (1903-1981); and Nasim Hijazi (1914-1996).

This conclusion, drawn with unequivocal certitude, is not entirely out of sync with the objective facts. Three main concerns drive our historical narrative: believing that the ‘personality’ of a historical character is the propelling force for the process of history; nursing a typically romantic view about the medieval past when Muslims were in power; and stressing exclusionism and exclusivity from other communities in order to strengthen our own identity.

One may argue that the influence of these three people has been central in shaping this three-pronged narrative in Pakistan. Nomani peddled the influence of the ‘personality’ by writing popular biographies like Al Farooq, Al Ma’amun and Al Ghazali etc. Hijazi accorded romantic colour to medieval Muslim history through his reader-friendly, accessible and elegant literary prose, and thereby galvanised the Pakistani historical imagination in a certain way. Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi tried to achieve the same but his means were different.

Unlike Nomani and Hijazi, Qureshi was a trained historian with the ability to marshal ‘facts’ typical of an academic well-versed in the positivist tradition. What also makes him distinct from the other two is his all-pervading influence on academics. His writings carry a thick layer of ideological veneering constituted of Islam and the quest for a separate identity of Indian Muslims, giving him a status of a guru for the right-wing ideologues and intellectuals in Pakistan.

Qureshi employs binary opposites while writing history. It is because of this reason that a dispassionate analysis of his works forms the theme of this column. Despite being well known in the Pakistani academic circles, very little information about his life and career is available in print. Therefore it warrants that a brief biographical account should be furnished below.

Born on November 20, 1903, in Patyali, a small town near Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh (then United Provinces), Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi belonged to a family of meagre means. After having passed the matriculation exam, he aspired to join the Mohammadan Anglo-Oriental College but the constrained resources of his family posed an impediment. He sought a teaching job at a government-approved school and pursued his studies as an external candidate.

His family suffered torrid time in the aftermath of 1857. His grandfather was subjected to severe grilling on the suspicion of his loyalty with mutineers. Thus, he grew up listening to pains his family underwent.

As a result, Qureshi developed antipathy towards British. It was probably this antipathy that led him to join the Khilafat Movement and Non-co-operation Movement in 1920. This was while he was preparing for his BA.

He was also influenced by Pan-Islamism, which remained the salient feature in the ideology that he professed through his history books. He subsequently became one of the main architects of such a political configuration which, although a nation-state, was underpinned by Pan-Islamic ideology.

It can be argued here that such a polity can hardly be contained within the confines of a nation-state.

Ironically, the revival of Muslim identity as a distinct socio-political reality was entwined with Pan-Islamism which weakened its link with Indian geography.

After the Khilafat Movement subsided, Qureshi joined the Al-Amman, a Delhi-based newspaper, and resumed his studies at St Stephen’s College. He obtained BA and MAs in History and Persian. After serving as a lecturer at his alma mater for a few years, he went to Cambridge to pursue his PhD in 1937, where he joined Rahmat Ali’s organisation, Pakistan National Movement. But he later got disenchanted with it.

For its academic rigour and precision, his PhD dissertation, The Administration of the Sultanate of Delhi, published later in a book form, is ranked as his best work.

Huma Ghaffar maintains that Qureshi once claimed he became Pakistani while in Cambridge, and so he said with a tangible measure of pride that he was a "much older Pakistani as compared to other Pakistanis".

Muhammed Iqbal and Rahmat Ali underwent similar ideological transformation during their stay at Cambridge. Many Hindu leaders too changed their ideological position while in the UK.

After having done his PhD, he came back to India in 1940, and was made a reader at the Delhi University. Soon after he was promoted to the post of professor and dean. Alongside he started working for the Muslim League.

In 1946, he wrote two pamphlets, titled The Development of Islamic Culture in India and The Future Development of Islamic Polity, published by All India Muslim League Writers Committee under the Pakistan Literature Series. In the elections of 1946, the Muslim League nominated him as its candidate from Bengal, and he became a member of the Constituent Assembly.

In the aftermath of Partition, a fire burnt his house in Delhi in 1948. The fire also destroyed his valuable book collection. According to some sources, Qureshi sought refuge at the newly-established Pakistan High Commission.

After migrating to Pakistan, Qureshi made it to the corridors of power as federal minister of education, information, interior and rehabilitation. He was also an active member of the Objectives Resolution Draft Committee.

He started writing history in 1954, and laid the foundation of Pakistan’s national narrative that resonates with full vigour to this day.

Between 1956 and 1960, he took up an academic position at the University of Columbia, and wrote The Muslim Community of the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, 610-1947. In 1960, he came back to Pakistan and became chairman of the Islamic Research Council. He worked as vice chancellor of the Karachi University for 11 years (1962-1973). His last assignment was as chairman of Muqtadara Qaumi Zaban (1979-1981).

Qureshi passed away in 1981 in Islamabad. He is buried in Karachi.

The next column will discuss his ideology and the method of binary opposites that he deployed.