Pakistani cinema must embrace the country’s treasury of literary works and adapt superior stories rather than churning out screenplays that fail to engage

In less than three weeks, we will welcome Eid ul Fitr and with it a string of high profile films that proudly claim to represent the new age of Pakistani cinema and collectively include the who’s who of the movie business.

Eid, celebrated in this part of the world with pomp and circumstance, is a festive occasion and the season usually entails big business for producers and exhibitors. And yet the sheer lack of enthusiasm for some, if not all, of these upcoming films (and their predecessors from recent history), has little to do with the cast, crew and exhibitors and everything to do with the stories that these films are trying to tell, or not as the case may be.

One venture that is threatening to appear this Eid is Hasan Waqas Rana’s Yalghaar, the war saga that has spent years in the making and includes Shaan Shahid, Humayun Saeed, Bilal Ashraf, Adnan Siddiqui, Armeena Rana, Ayesha Omar and several others. Forget for a minute that it is fueling a state-sanctioned war rhetoric. Just look at how the trailer is cut and you will see the amateurish feel that persists throughout. Not only is it jarring but it makes you wonder if the money spent on this film could’ve been put to better use.

Another example is an upcoming film by Yasir Nawaz, the peculiarly titled Mehrunnisa V Lub U that counts in its cast actors Danish Taimoor, Sana Javed, Javed Sheikh, Nayyar Ejaz and Saqib Sameer.

When asked if the film is drawing inspiration from across the border, especially keeping in mind the Yash Raj inspired sequences that can be found in the trailer, Taimoor told Instep: "Pakistani films were being made like this many years ago as well. We used to have item numbers and make films in the same manner. Our conflicts are the same; our style of storytelling is the same. Of course our films will look similar. And even if they look similar then what’s the problem? Bollywood does well in Pakistan. People run to the cinemas to watch Indian films. So if our films look the same then that just goes to show that we’re making films that the audience wants to see."

We neither have the budget that goes into one mainstream Bollywood film nor do we have the stars who can push an average film into the coveted 100 crore club. The logic, therefore, that Bollywood is popular so we must ape it, is skewed.

Before anything else is put in motion, it must be understood that a compelling story matters the most. Films appeal to us because they are primarily about storytelling and the stronger the idea, the more enriched the experience for the viewer. Without compelling stories, one film blends into the next until you’re unable to recall any of it. Half-baked ideas don’t register.

In the post-revival age of Pakistani cinema, most films seem to be banking on a bag of tricks (glamour, loud music, Bollywood ethos and stars) instead of its actual core: its story. In other words, a lot of these productions are lacking. It isn’t about aesthetics (though that too merits a discussion at some point) so much as it is about the foundation.

Fortunately, the solution to this potentially-harmful industry trait that can take us back to struggling times can be found in literature, specifically in Pakistani fiction.

Whether it is in English or Urdu, Pakistani fiction is full of remarkable stories and memorable characters and all we really need to do is figure out how to adapt those stories for the big screen.

The idea may sound daunting at first, preposterous even, but adapting literary works is not a new idea particularly when one pays attention to industry norms that go beyond local turf.

The works of Rabindranath Tagore have been adapted to the silver screen in India (Chokher Bali), the works of Chetan Bhagat and Saadat Hasan Manto have also inspired films across the border. Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist got its own movie by Mira Nair and reports suggest that Moth Smoke, another book by Hamid, will be adapted for the big screen with Irrfan Khan attached to star. Speaking of Irrfan Khan, how could we forget The Namesake, an adaptation of Jhumpa Lahiri’s prize winning novel?

Similarly, BBC’s Sherlock, the TV series that turned Benedict Cumberbatch into a global superstar, was drawn from the works of Arthur Conan Doyle. Several films that competed for an Academy Award this year such as Moonlight, Arrival, Fences, Hidden Figures and Lion were adapted from books. HBO’s revered Game of Thrones is also based on best-selling books by George R.R. Martin while Pakistan’s very own Manto which featured Sarmad Sultan Khoosat in the titular role also drew its narrative from the works of the late writer. The list goes on and on and on…

Spoilt for choices

Now that we’ve established that the precedent for adaptation exists, we can focus on the writings. Spend enough time pouring over the works of Pakistani authors and what will emerge clearly is that multitudes of genres have been explored by these wordsmiths. From religious extremism to the pain of partition to the violence and crime simmering just underneath the surface, the writers are willing to talk about the hard truths that stay unsaid far too often.

While the history books present selective truths and remain impervious to the past, it’s the fictional accounts that carry wisdom and reflection of the ages.

One great example is master storyteller Ibn e Safi, who wrote humourous detective novels in Urdu. His creations include two mystery series, Jasoosi Dunya and the Imran series, and both still hold a permanent spot in literary history despite the passage of time. Having read some of the English translations, I can honestly say that the witticism found in Safi’s books is second to none and maybe his greatest strength. Plus, the characters have a strong back story and nothing is binary.

Take the titular character Imran from Safi’s Imran series. He is 28-years-old when we meet him in The House of Fear. He has a PhD in sciences but displays buffoonery on a daily basis. One day he wants to start a business in scientific equipment while the next day he wants to open a science institute. One minute he talks about dying because of being choked by his own tie and the next minute he loses his train of thought and embarks on a completely different mission. Amusing and unpredictable, Imran is also a superb detective and the Intelligence Bureau relies on him for lending expertise. One minute he is hysterical and talking about "real love" while the next minute he goes about inspecting the crime scene with such observation that he notices things no one else picks up on. He appears to be a madman and a fool in public but he is neither.

Safi, accused of being a "popular" writer, wrote for the average man and that means that his writings are approachable and possess universal appeal. Instead of making assumptions about the audience and whether they will accept something different, one only needs to look to Safi to find a narrative which will make us laugh while keeping up the thrill of the chase that makes murder mysteries so very effective and appealing.

Another brilliant example, an adaptation that must happen, involves top cop-turned-crime novelist Omar Shahid Hamid. Having penned three terrific crime novels with The Party Worker being the most recent release, his work evokes a volatile world that is all too familiar to so many of us.

In Party Worker, Hamid tells the story of Asad Haider, an assassin who is the chief hit-man for Karachi’s largest political party, the United Front and the characters that make up his orbit. Haider is involved in cases of rioting, arson, burning cars, assault. But the story begins when he is shot in broad daylight in New York and it becomes instantly clear that he was set up by the very people he spent his life protecting. One of them is the Party founder, the Don, who has spent the last decade or so ruling the city with an iron fist from New York. It includes a cop who is above reproach as well as a string of characters who live in the grey and how their lives are intertwined. The theme of betrayal runs deep and shapes the narrative in exquisite fashion. It evokes a climate of uncertainty that is actually felt in a city like Karachi.

As Livemint rightly noted, "Hamid’s familiarity with Karachi is evident, and the chapters set in the city are a pleasure to read. From Ismail, an unscrupulous journalist looking to make a quick buck through blackmail and other nefarious means, to Baba Dacait, a notorious gangster who has emerged as the only opposition to the Party’s misrule, most of his characters are earthy and believable. In this Karachi, one will find children kicking around a severed head on a football ground, but the blood and gore is leavened by some gallows humour (at one point, Baba Dacait half-seriously considers hiring suicide bombers in bulk to blow themselves up outside his rivals’ offices)."

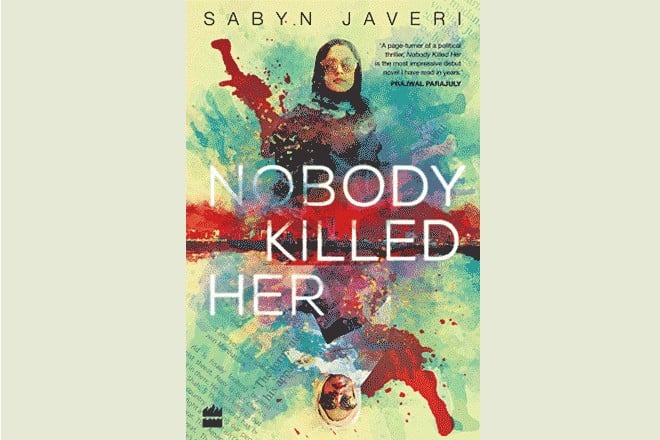

Political intrigue is also a recurring theme in Sabyn Javeri’s riveting debut, Nobody Killed Her. Telling the story of two radically different women, their complicated relationship to each other and to power, it is a page-turner that could make for a thrilling adaptation. It’s a powerful narrative because it is focused on two women who do not conform. Rani Shah is the former Prime Minister whose assassination opens the plot. Accused of this murder is her confidante Nazneen Khan.

One is born in privilege while the other comes from a darker world, one where her family is massacred and there is no justice.

As the book moves between the past and the present, the intense relationship between these two women in a climate fueled by patriarchy and religious fanaticism tells you more about the human condition than any Pakistani film in recent history. It is also about how leaders fall from the pedestal and are as human as the rest of us.

There are plenty of other examples. Mohammed Hanif’s debut novel, A Case of Exploding Mangoes, is a dark satire that centers on the plane crash which killed General Zia ul Haq and is told through the narrator Ali Shigri, who is a Junior Officer in Pakistan Air Force. In Our Lady of Alice Bhatti, also by Hanif, the narrative follows a Christian nurse working in a hospital in Karachi.

Bapsi Sidhwa’s Ice Candy Man deals with the tragedy of partition while The Crow Eaters shone a light on life in the Parsi community in Pakistan. Daniyal Mueenuddin’s excellent collection, Other Rooms, Other Wonders, of connected stories about a landowning family in Punjab captures rural Pakistan with eloquence and precision.

In a review for The New York Times Dalia Sofer noted, "In this labyrinth of power games and exploits, Mueenuddin inserts luminous glimmers of longing, loss and, most movingly, unfettered love. But these emotions are often engulfed by the incessant chaos of this complicated country. As Lily tells her eventual husband in a rare moment of quietude: "You know what’s amazing, we’re actually alone here. That never happens in Pakistan."

The Wandering Falcon by Jamil Ahmed echoes the stories of those who live in the tribal areas in empathic layers while H.M. Naqvi’s slick writing in Homeboy captures the 9/11 world with intuition and honesty.

Writers like Intizar Hussain, Mushtaq Ahmed Yousufi, Nadeem Aslam, Kamila Shamsie and Musharraf Ali Farooqi also have exquisite writings to their credit and they would also make for excellent film content.

The bottom line: it is time we embrace Pakistani fiction and all its layers to fulfill our desperate desire to keep cinema not just alive but exciting, engaging and visceral.