Sarfraz Iqbal, Lahore’s last ‘Lollywood’ poster artist, looks back on a 50-year-career

It takes us (my photographer and I) a good 20 minutes or so to find his office. The tiny lanes are claustrophobic and busy as we drive past tea-sellers, donkey carts, badly parked cars and motorbikes, printing shops and offices that seem to spill over in a mesh of weekday chaos. We are in Royal Park, in Lahore.

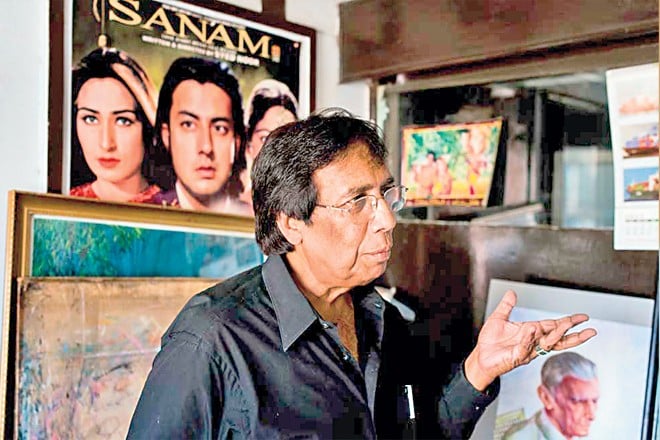

Seated at his desk and dressed in a black button-down and cream-colored pants, Sarfraz Iqbal (or ‘S Iqbal,’ as he’s more commonly known) greets us with a warm grin, apologizing profusely for not being able to send his attendant downstairs to guide us to his office. The attendant is away, he mentions, and then apologizes again.

Iqbal’s work spans decades -- from 1962 until today, Lahore’s last Lollywood poster artist (who draws by hand) is still at it. "My interest in my art has never diminished. The day I stop working, that’s the end of me," he says, half-joking, half-serious.

The love of art came from Iqbal’s father, S. Khan, a very well-known and well-respected poster artist in Bombay, India, at the time. "My talent is inherited from my father and it’s because of him that people recognize me," says Iqbal with pride. "He’s the pioneer of this field in Lahore. When he immigrated to Pakistan in 1947, he introduced cinema decoration and poster design in the city. Even though he had competitors at the time, he never stopped teaching people the craft of poster design."

"My father used to say, when you want to learn something, learn it like a stupid person. That’s what I did with my craft." Even though Iqbal’s mother encouraged him to take up art, his father wanted him to get an education first. And so he did. "I wanted to quickly graduate and start working in this field," Iqbal states, "So as soon as I completed my undergraduate degree from Forman Christian College in Lahore; I started cinema decoration work with my brother. But I didn’t like doing it very much."

"I don’t have typical artist habits: growing out facial hair, et cetera. I’ve always been suited and booted when I work." Iqbal says, cracking up, "People say there’s a guy in Royal Park who’s really well-dressed! I had foreign teachers at college, so their ways rubbed off on me."

Having worked with everyone from W.Z. Ahmed, Masood Pervez, Hassan Tariq, Khurshid Anwar, and countless other Lollywood heavyweights, Iqbal reminisces about Lollywood’s glory days. "The crew would work like a family. There was no difference, everyone was equal. I never felt like I was just an artist and they were actors or higher-ups. It wasn’t like that. Everyone’s input in the movie was considered. That’s why the movies turned out so good. The entire film would be based on teamwork."

Pakistan’s film industry has suffered grossly over the years -- it went into decline thanks to censorship policies and the like, following General Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamization of Pakistan from the tail-end of the ‘70s. Even though a new breed of independent Pakistani filmmakers have begun to offer local audiences alternative cinema in the form of thought-provoking storylines (staying far away from formulaic Lollywood themes, song and dance), a mass revival of Lollywood is barely stirring to life.

"We don’t have any good people left in the industry," states Iqbal dismissively. "Good work isn’t being done. Yes, we have a few such as Syed Noor, Shahzad Rafique, Hassan Askari -- the juniors who became the seniors in the industry, but the new generation hasn’t really learnt the art properly. They just have one goal in mind: to make a movie. Yes, it’s a technical job, but they have not learnt the creative part of making a movie. No study, no research!"

Iqbal reveals how educated and refined practitioners in the industry used to be in the past. "Did you know W.Z. Ahmed used to be a CSP Officer? As was Fazal Ahmad Karim Fazli, and Anwar Kamal Pasha. Oh, and Khurshid Anwar had an MA in Psychology! Since I worked with them, isn’t it obvious I must’ve learnt a lot from them? Their education really polished them. It was like this even in India. Education played a big role in the success of the film industries in India and Pakistan in the past and my analysis is that the younger generation hasn’t educated themselves by learning from the greats."

Even though both of Iqbal’s sons take after him vis-à-vis art and creativity, the artist has begun to feel an intense need for passing on his knowledge to a bigger audience. "Students in Lahore keep approaching me from time to time," he says, "And I ask how I may help them. It’s my duty to teach them this art form. Why don’t our local universities avail themselves of our talents? This is where we go wrong in Pakistan, we don’t educate our people, we don’t pass on our talents."

Mentioning M. Ismail, an art director who used to work in Bombay back in the day, Iqbal states: "He used to say filmmakers are magicians. They were thinkers. They were hardworking. But these days those movies that are a success are mainly because of their music, because about 75 per cent of the movie’s success is based on its soundtrack -- it can make or break a movie. Even bad actors in India, if the music in their movies are good, the movies are a hit. Else the film’s equal to zero without the music."

Pulling out a small notebook, Iqbal flips through pages upon pages of Lollywood movie titles (alongside the directors’ names), all penned in neat, clear handwriting. He tells me he’s making a record of all the posters he has made until now. Someone in Lahore is writing a book on Iqbal and she’s asked him to try and put together copies of his posters. He laughs. "My biggest regret is that I never kept a record of my posters," he says, while rifling through his notebook, "I’ve spent such a busy life, I just never bothered. I don’t have a single copy, but I’ve started looking for and collecting them bit by bit."

He has a few, he adds, but he knows he won’t be able to get his hands on each one. Too much time has passed. "I’ve painted so many posters for so many films; I don’t remember all of them. At one point in Pakistan, in one year alone, 150 films were produced. This was, I think, 20 years ago? And I made the posters for 95 of those films. In a year!"

"There’s a lot of creativity in manual work," Iqbal says thoughtfully. "Out of a few thousand images I end up selecting three-four pictures that tell you about the movie -- if it’s a cultural film, an action film, a romantic film, or a family film. I need to know about the outline of the movie. Then, according to that, I work. I’ve always been working according to the subject of the film. For instance, if the film is something related to family, the poster should represent that. If the film’s called Love’s Promise, then the poster should represent that. I’ve never let the name slip from my work. I also do some of the copywriting for my posters myself. See, look," he says eagerly, pointing to a caption above a current sketch of his on the desk, "I wrote this to go with the poster: ‘Live for Future. Make it Sure.’"

Drive past any local cinema house in Pakistan today and you’ll see poster upon poster of buxom babes (displaying ample cleavage) and sweaty, snarling, bearded heroes. The posters are vulgar at best, luring in audiences via promises of sex, action, and aggression. "I’ve been offered money to make these posters in the past but I’ve always refused. I have daughters, a wife," Iqbal says, "I haven’t made a single one. The uneducated directors who entered the film industry and started making movies on thuggery and the gandasa culture, they ruined everything."

Currently working on a few posters and his upcoming exhibition, Iqbal reveals that he often finds himself waking up in the middle of the night.

"I just feel this need to work constantly and that keeps me up at night. I have a blood pressure issue too, because I have a bit of a temper…"

Does he get angry because he feels the need to be more creative, I ask gently.

"Yes," he responds quickly. "Yes. I feel the need to be more creative. I practice every day." He hands me a thick sketch pad full of portraits of men and women -- some are celebrities, local and foreign. "I sketch every day in this book, like a child," he says with a laugh.

- First published in Asia Society in 2014

- All photos by Saad Sarfraz Sheikh