David Hockney’s recently-concluded retrospective at Tate Britain reaffirmed the artist’s life-long love for paint. His works from 60 years are not purely paintings; these include photographic assemblages, drawings, and digital-based visuals but the common element in all of them is the artist’s skill in ‘constructing’ his imagery.

In a sense, the Bradford born (1937) painter can be called the architect of images. Hockney studied at the Royal College of Art where, during the convocation of 1992 in which he was awarded the Honorary Degree (Doctor of Arts), Christopher Frayling, the Head of Cultural History, said that every student of RCA had to submit a dissertation in order to acquire degree but David Hockney did not write a single line. The institution had to award him MA, he said, because by the time he was a student at RCA, he had already become a celebrated painter, recognised beyond Britain.

Recalling those years spent at RCA, Hockney’s friend and fellow artist R. B. Kitaj describes their first encounter in 1959: "I spotted this boy with short black hair and huge glasses, wearing a boiler suit, making the most beautiful drawing I’d ever seen in an art school. It was of a skeleton". Kitaj bought one skeleton drawing for 5 pounds immediately, but had to spend thousands of pounds to get the second skeleton drawing after several years.

The exhibition at Tate reveals Hockney’s facility for image making, particularly the portrait of W.H. Auden, in which the artist has captured the form, moment, mood, and the state of the mind of the poet. Lines in ink mapping his outline, his extended hand, and ash dripping from his cigarette transport us to Auden’s presence and poetry.

One cannot detach the maker from the creation, since any creative person’s output is a reflection of his self as Henry Geldzahler observes: "David Hockney’s art has been lively from the first because he has conducted his education in public with a charming and endearing innocence". This aspect of delight but not innocence is evident in his early paintings in which the artist, instead of following and favouring a ‘naïve’ style of depicting human bodies and distribution of colour, deliberately employed various tactics of picture making; in a single canvas (Play Within a Play, 1963) one can see figures and plants drawn like a child, spaces rendered in a mechanical manner and objects painted in a naturalist way.

Another work from the same period, in which a man represented in a stylised scheme and surrounded by cubist forms, is titled Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices (1965). The canvas confirms the artist’s interest in constructing a language that relates to the history of art, especially to Cubism.

Explaining this movement that had always fascinated him, Hockney in his tiny book Picasso, writes: "Cubism destroyed the fixed viewpoint. A fixed viewpoint implies we are standing still, and that even the eye is still. Yet we all know that our eyes move constantly, and the only time they stop moving is when we’re dead -- or when we’re staring. And if we’re staring we’re not really looking". Hockney experiments with the Cubist aesthetics in his photomontages where a singular picture is disintegrated into multiple Polaroid photographs, which combine/communicate diverse sides of subject. Talking about these, Hockney in a conversation with Martin Gayford shares his experience and excitement: "I felt I had made a photograph without Western perspective. It took me a while. I didn’t know much about Chinese art, even when I went to China. The photography I did took me to Chinese scrolls."

Viewing the exhibition, which is not called retrospective but Hockney (60 Years of Work), one senses that Cubism has been an integral ingredient in forming the pictorial language of the artist. This obviously refers to multiple views, for example his landscapes from Los Angeles in which a scene, like a Chinese scroll, is stretched, scattered, spread and split in order to give a ‘holistic’ sense of space.

Hockney performs with perspective in various manners, especially the panoramic views of East Yorkshire, the Grand Canyon and roads to his studio in the Hollywood Hills, from 1980s to 1990s, in which crop fields, trees, terrains, road, and pathways tilt, twist and move to create a contorted, yet complete and complex parallel of reality. On his return to his native Yorkshire in 2006, Hockney produced large canvases, again landscapes with brilliant colour and stark contrasts, a reality that is emotional, emotive and exuberant (in their intensity of hues and interwoven brushstrokes, these paintings remind of Vincent Van Gogh).

Commenting upon his way of approaching issues of representation, Hockney elaborates: "Artists thought the optical projection of nature was verisimilitude, which is what they were aiming for, but in the 21st century, I know that is not verisimilitude. Once you know that, when you go out to paint, you’ve got something else to do. I do not think the world looks like photographs. I think it looks a lot more glorious than that."

But before the 21st century, David Hockney created some of the glorious views, visions and variations of reality. Paintings from the 1960s unfold with ease an uncanny aspect of picture-making. These canvases, combination of loosely drawn figures and scrawled writings, suggest the artist’s joy in exploring his medium and subject matter. However, more than pleasure, it is the careful and clever compilation of visual vocabulary that distinguishes Hockney from other artists, and has inspired generations after him.

At the Tate Britain, one notices the way painter has made use of bare canvas, thin layers of colour and flow of brushstroke to capture some of the most difficult subjects. For instance, in the room with bathers (men in pools or showers) the depiction of water enchants a viewer, especially Man Taking Shower in Beverly Hills (1964) and A Bigger Splash (1967).

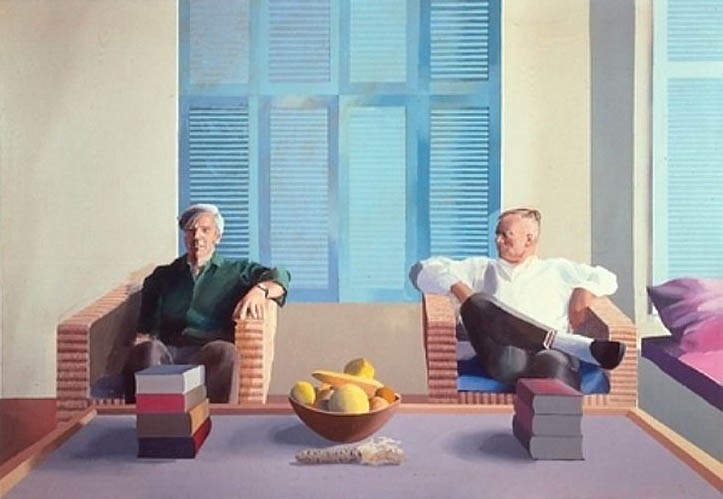

This command on reality, to transform it as a grand narrative, is visible in his paintings with figures of collectors and friends; normally grouped in two, these compositions move beyond mere appearances. The artist aims for an experience greater, wider and lasting.

Seeing his painting seems like believing in the world, what he manages through a series of intelligent pictorial decisions. For instance, in the double portrait Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy (1968) figures are painted with carefully observed tones on their faces and bodies, but the fruit placed in a bowl on table, corn next to it and two piles of books on either sides are executed in flat, selective, even plain colours. Yet when we interact with the painting, we feel more in the presence of actual people, than being in front of a still picture.

Following that phenomenon, Hockney experiments with technology, by making images on iPad. Not surprisingly, some of these digital images defy the aesthetic of camera and connect this gadget to traditional tools of drawing i.e., crayon, and pen and ink which, perhaps are exploited best in the hands of David Hockney. Thus, many characters, drawn in sparse lines and patches of coloured crayon appear alive. And still seem to talk to a person who may have come out of the show but the exhibition has not left him!