The state must rethink the Rewaj Bill to end controversy over Fata’s merger with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

On 15 May, the government introduced the Tribal Areas Rewaj Act, 2017 in the National Assembly to judicially integrate Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata) into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

The Act is a recipe for disaster for mainly three reasons. First, the proposed Rewaj Bill hinders judicial merger. According to its article 2 (j), "Rewaj means customs, traditions and usages of the tribes in vogue in Fata." ‘Statement of objects and reasons’ of the proposed act states: "The Rewaj Act for Tribal Areas, 2017 focuses on the introduction of a legal system which will provide for retaining the Rewaj."

As a matter of fact, judicial merger inevitably requires the application of same laws throughout the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. If implemented, the jirga system will cease to exist. This is a flawed reasoning.

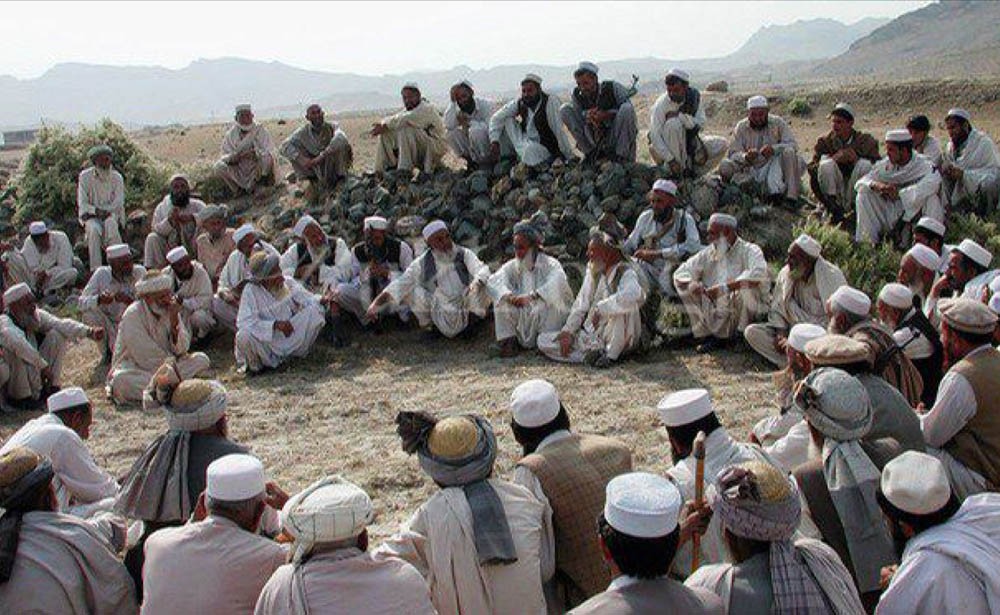

However, the fear is totally unfounded. Jirga remains the principal mechanism of conflict resolution among the Pashtuns in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Balochistan and elsewhere in the country despite the fact that the entity does not enjoy any legal recognition. The question is why jirga needs any de jure status in the Pashtun populated tribal areas where tribesmen prefer the de facto Olasi jirga (peoples’ council) over its de jure Sarkari jirga (government’s council) counterpart.

Although a number of Pakistani laws have been extended to Fata, the act renders them subservient to Rewaj. As second schedule shows, three procedural laws -- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898 (Act V of 1898), the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (Act V of 1908) and the Qanun-e Shahadat, 1984 (PO No. 10 of l984) -- and 141 ‘other laws’ are extended there. As per section 3 (2), "In case there is any conflict between the provisions of this act and any other law, including the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC), Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) and the Qanun-e-Shahadat, 1984 (PO No. 10 of 1984), for the time being in force, the provisions of this act shall prevail to the extent of the inconsistency". Similarly, section 4 (2), and 5 (2) reads, "Notwithstanding anything contained in the CrPC [and CPC], the judge shall adopt such procedure which facilitates compliance with the provisions of this act and secures the ends of justice in accordance with Rewaj".

Second, despite the extension of the jurisdiction of Supreme Court of Pakistan and Peshawar High Court -- under section 14 (1) and (2) respectively -- and the abovementioned laws to Fata, a close reading of the bill shows that it is, in a number of ways, a reincarnation of the FCR. According to section 20 of the Tribal Areas Rewaj Bill, 2017, "The Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR) 1901 is hereby repealed". The word "repealed" is too strong a word to use when parts of the FCR are still enshrined in the proposed legislation.

According to section 2 (a), a "Council of Elders means a jirga of four or more respectable elders appointed under sections 8 or 10, as the case may be, and presided over by the Judge." Like previously under the FCR, the act gives jirga the role of arbitration under section 2 (b), which reads, "Court" means the court comprising the judge and the Council of Elders." According to section 7 (2) and section 9 (1), council of elders is nominated by a judge in a civil and criminal references to the court respectively. Likewise, under the FCR, the judge is not bound to issue a verdict in accordance with the findings of the council of elders as per section 7 clause 7 (b) and section 9 clause 4 (b) of the Rewaj Act.

Third, the proposed legislation, like the FCR, cedes state’s authority to a non-state actor, jirga. For one, the act, like FCR, does not apply to all Fata but to ‘protected areas’ only. Under FCR, in ‘normal’ circumstances, some 10 per cent of tribal territory is ‘protected area’, an assistant political agent told me. The proposed bill does not change anything. Section 1 (2) reads: "It [Rewaj Act] shall come into force in… Protected or Administered Areas." Practically, this means that in the 90 per cent unprotected area, state abdicates two of its core functions, arbitration and implementation of laws, to a non-state entity called Olasi jirga (people’s council). In the remaining 10 per cent area, called ‘protected’ or ‘administered area’, state outsources arbitration as Sarkari jirga (government council) performs the function.

In a nutshell, state loses huge ground to a non-state actor, jirga.

As a result of state’s abdication and outsourcing of its authority under the FCR, Fata has served as a breeding ground for militants to capitalise on weak state conditions. This is as true of post-independence era as it was under the Raj.

The British Ambela campaign of 1863, Maulana Mehmoodul Hasan’s armed struggle codenamed Tehreek-e-Reshmi Rumal in 1916, Amir Amanullah Khan’s mobilisation of tribesmen during the Third Anglo Afghan war in 1919 and Faqir of Ipi’s insurrection in 1937 are some of the high profile instances of armed mobilisation on the frontier before partition.

After independence, from Kashmir jihad in 1947 to the continuity of Faqir’s resistance till his death in 1960 to Fata’s mobilisation as a launching pad during the era of Afghan resistance to the rise of Afghan Taliban in the 1990s to the outbreak of Taliban militancy on the frontier in the wake of Taliban’s ouster, armed mobilisation in the tribal areas has been a rule than an exception. Loose administration has been one of the main reasons for militant activity in the tribal areas. How such deficiencies can be overcomed?

The ‘same old wine in a new bottle’ approach must end. State must have exclusive monopoly over legislation, execution and arbitration. Similarly, the repealing of the FCR should be accompanying the full merger of Fata with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. This means the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata) must not be transformed into Provincially Administered Tribal Areas (Pata) because the latter, some of the most backward areas of the province, do not stand out as examples to be followed. If we want to prevent new disasters on the frontier, then complacency is a bad omen for the pacification of the tribal belt.