A historical perspective of mainstreaming -- looking at the cases of JUI and JI

For a historical perspective of mainstreaming of religion-based activism, let’s take the cases of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI) and Jamaat-e-Islami (JI). Both these curious examples can point to a complicated nature of our politics that dates back to pre-partition times.

Take, for example, the JUI that professes the heritage of Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind (JUH) and Dar-ul-Aloom Deoband. Its genesis points to a time in 1942 when its founder Maulana Shabbir Ahmed Usmani parted ways with the JUH to support the idea of Pakistan unlike his comrades. After creation of the country, the JUI was successful to gradually attract back those political activists who resided in Pakistan. In between the Majlis-e-Ahrar (1929-1954) under leadership of Chaudhry Afzal Haq and Syed Ata ullah Bukhari originated from the same source the JUH. It even rose to electoral politics in Punjab and had become an important actor on behalf of Punjabi Muslims. After the Anti-Ahmedia riots in Lahore (1953), which it spearheaded, it was banned.

It’s often perplexing to observers that how come a group which believed in Indian nationalism, anti-imperialism and social reformation of Muslims under the leadership of the likes of Maulana Mehmood ul Hassan in United India, changed their colours in Pakistan and shifted to sectarian politics after creation of the new state? While Maulana Mehmood ul Hassan and other JUH leadership consciously used "non-Muslims" instead of "Hindus" just not to hurt feelings of that community, their acclaimed devotees in Pakistan started their public presence by stirring an Anti-Ahmedia movement. This can perhaps be attributed to two major defeats to especially the Punjab-based activists -- the Khilafat movement and the very creation of Pakistan.

Read also: The real test

This also signifies problems of mixing politics with social reformation based on religion and dependent on religious communication. The role of mainstream leaders in playing the religious card cannot also be discounted; which in the case of tussle between then Chief Minister of Punjab, Mian Mumtaz Daultana, and the prime minister, Khawaja Nazimuddin became so evident in the form of the Anti-Ahmedia Lahore riots that also provided a window of opportunity to the JI and the Majlis-e-Ahrar to gain some political space.

What is important here is to look at how political rather than ideological compulsions were driving these forces to make a room in the new state of Pakistan. The passing of the Objectives Resolution (1949) and its impacts are frequently highlighted in the Islamisation process of Pakistan, but it is often conveniently missed out that the first speech in favour of this resolution came from Sir Zafarullah Khan who was a staunch Ahmedi by religious conviction. So its drafting by Zafar Ahmed Ansari, review by JI head Syed Abul-al-Ala Maudaudi (while in jail) and pushing forward by Sir Zafarullah Khan to consolidate rule of the then Prime Minister will dilute the arguments that ideological schools present today.

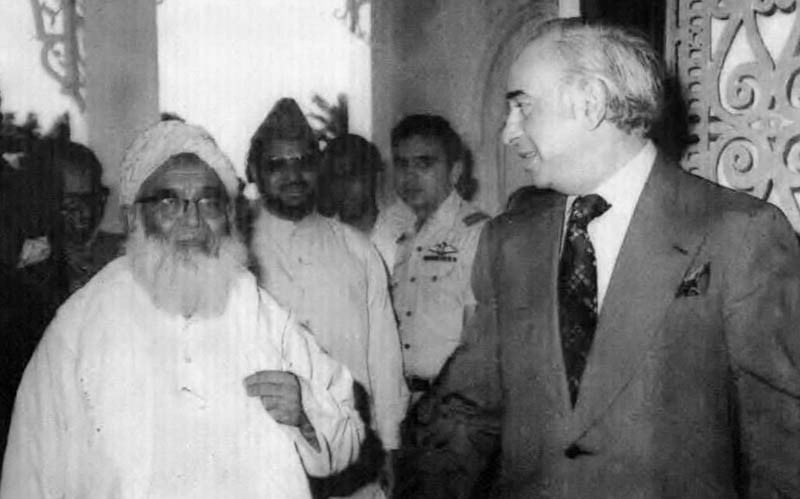

The JUI came into active political scene when Maulana Mufti Mehmood took its reign in 1962. It is interesting that its sphere of influence is concentrated in (now) KP and Pashtun-dominated areas of Balochistan. Maulana’s anti-imperialist agenda of the JUH days had turned into a campaign against modernisation policies of Gen Ayub Khan. He, however, opposed the candidature of Mohtarma Fatima Jinnah against Gen Ayub Khan on the basis of his stand that women cannot be head of the State.

Even though the religious political parties had won 18 National Assembly seats out of a total of 40 seats by opposition parties sitting in the National Assembly of Pakistan, they took active part in framing of the new Pakistan in 1972-73 and were successful in bringing the relationship between the state and religion on top of the constitutional debates. Recurring controversy over details of an "Islamic Constitution" of Pakistan was reverberated during the session which was convened during boycott of the opposition parties over removal of the NAP Balochistan government but given the importance they ended the boycott and participated.

Then law minister, Abdul Hafeez Pirzada, introduced the Constitution Bill in the assembly on February 2, 1973. The main opposition parties formed a United Democratic Front (UDF) under Pir Pagaro’s leadership on March 2, 1973. The constitutional framing committee comprising of 25 members held 48 sittings of a total 175 working hours, spreading over a period of 38 working days in all. The opposition parties in the Assembly resolved that they would ‘resist all efforts to pass an un-Islamic, undemocratic, non-Parliamentary, and non-federal Constitution, and that if their legitimate amendments were not accepted, they would have no choice except to go to the nation’.

Read also: Prize for peace

These sessions also frequently witnessed brief boycotts by opposition. The opposition tabled 300 Amendments on the first 40 Articles. The passing of the 1973 Constitution with almost unanimity (with 3 abstentions) presents a successful framework where conflicting ideologies and interests could live side by side within a negotiating State.

If we look at the Islamisation drive under Gen Ziaul Haq, it seems inspired by proposals of the religious political parties within the constitution committee of 1972-73 and ultimately damaged the social contract signed by the then representatives of the Pakistani people.

The Gen Zia era also witnessed mass scale recruitment and mushrooming of militant groups for the Afghan jihad by affiliates of the JI and JUI; even though the latter was part of the MRD movement against the dictatorship and also endorsed the governing of the state by a woman. In the later dictatorial period of Gen Musharraf, the religious parties were facilitated to form the government under the banner of MMA. The JI affiliates having control over campuses were successful in transforming its cadre into an enterprising force that with its trained human resources, entered mainly into the education business after privatisation of the education sector under the structural adjustment programme.

It is estimated that around 17000 schools in the mainstream education sector are now being run by the JI affiliates who might not be part the core cadre of JI presently but were trained there. The biggest school systems of Punjab and KP provinces are owned by the JI veterans among other leading school systems in both provinces. This form of reintegration is, however, not without its problems, especially when it comes to the core guiding conceptions of the State.

For foot soldiers of militants coming from madrassas it will be even harder to reintegrate them. In both cases, the socio-economic mainstreaming of marginalised areas, i.e., Fata, Balochistan, etc; structural adjustment through education system, and reforming the standards of a mobilising agency of media may do for nation-wide changes.

At present, however, our emphasis is upon values and morals which primarily make changes in individuals and not the groups.

Can we now imagine the atmosphere of the constitutional proceedings of 1973 where Maulana Mufti Mehmood could demand that despite his belief on prohibitions in Islam, slavery was allowed in some cases; and in contrast Sheikh Rasheed would constantly try to insert clauses about socialism in the constitution? In the process, the state’s role as a mediating agency was established. When this role is compromised for political expediency or other interests of dominant civil and military institutions, the state is likely to be perceived as an actor in the conflict not its mediator and resolver.