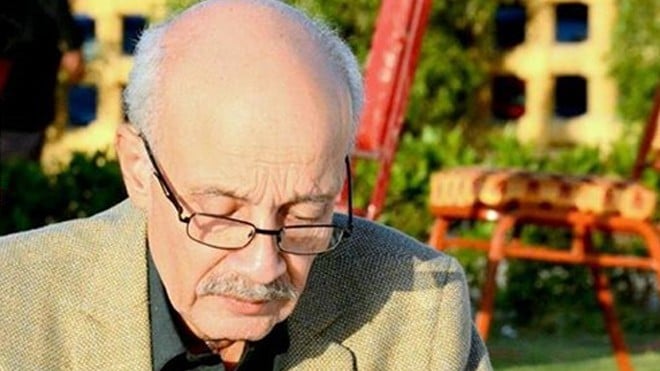

As a political worker, Latif Mughal believed firmly in workers’ solidarity, tolerance for disagreement and much more

It is impossible to define Latif Mughal’s contribution to the workers movement, as well as his role as a political worker, solely because there is no category spelt out for the range of work he delivered as part of the various hats he adorned in his brief life.

Latif Mughal was born in Karachi 1959 in Haji Camp in a working class family. He studied International Relations from the Karachi University and went on to join the Pakistan Peoples Party in the 1970s, in his teenages, and remained with it till his death. Benazir Bhutto appointed him member of the party’s Karachi Executive Committee in 1987 and he served in this capacity until 1995. He also worked as political secretary with the PPP’s then provincial president, Qaim Ali Shah, from 1987 to 1994. He contested the local government elections for the general councillor’s seat in 1987 and defeated his rival MQM’s candidate.

As any other jiala, Mughal faced fake cases and arrests (in 1979 and 1987). He remained active against General Pervez Musharraf’s regime and used his documentation skills to collect evidence against the government’s dictatorial practices, including the scandalous KESC privatization. During the years of Benazir Bhutto’s self-exile, Mughal, along with Taj Haider, Habibuddin Junaidi, Shaikh Majeed, Manzoor Badayuni and other committed PPP workers, ran the Peoples Secretariat in Karachi and kept the party alive. At the time of his death, he was member of the Party’s Sindh Media Cell at the Bilawal House.

Mughal joined the then Karachi Electric Supply Corporation in 1979 when he was hardly 20 years old. He was the founding member of the Peoples Workers Union formed in 1985. The union struggled for workers rights in the corporation and fought tooth and nail against the privatization of the corporation executed by the Musharraf regime in 2005. The controversial privatization finally led to the handing over of the KESC management to the Abraj Group that launched an immediate downsizing, expelling thousands of workers (official figure is 4,800, though union leaders state that the actual number was much higher than this).

Mughal was also forcefully sent packing till he acquired a stay order from the court against the KESC’s move. However, the stay order could not prevent KESC from withdrawing his medical benefits, leaving him with a basic salary or hardly Rs 20,000 per month.

Unfortunately, it was around the same time that he was diagnosed with Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma, which stayed with him for over 13 years, eventually taking his life on April 17, 2017.

His friends recount his very peculiar style of working, his tolerance for disagreement, his dedicated commitment to engaging a democratic process for political struggle, his very firm stand on working across differences for a common cause, his strong belief in workers solidarity , and finally the power of documentation to strengthen a struggle.

Around the time of privatization in 2005, KESC Labour Union, a rival of the PWU was elected as the Collective Bargaining Agent of the corporation. A traditional polarised trade union approach would have demanded that all three unions attached to the corporation, People’s Workers Union (PWU) and United Workers Union, fight for the same cause in a divided direction. However, Mughal championed the agenda of a joint struggle and persuaded PWU as well as UWU to ally with KESC Labour Union and fight collectively against the privatization. Together they launched a dedicated movement to resist privatization and dismissal of workers in 2011, running a months’ long camp at the Karachi Press Club.

Mughal’s colleagues are all unanimous that he embodied the true character of a political worker. "He had the distinction of being a worker that the party should be proud of, rather than the other way around," says Karamat Ali of PILER who worked closely with Mughal since the start of his political work. He neither sought a position nor any favours from the party. In fact he used his unique position as political and union worker to benefit both the platforms that he was attached to. Despite Peoples Party endorsing KESC’s privatization by way of a 2009 agreement, he walked the difficult path of staying in the party ranks as well as with the union, strongly pursuing his approach of a democratic engagement to persuade all to resist privatization collectively.

One of the many jobs that he carried out as a political worker of the Pakistan Peoples Party, was the ground work before party’s nomination for candidates for elections. He would visit constituencies of the candidates, meet members public and gather information about the candidates work and conduct from the locals, filing a thorough report with the party. "Benazir Bhutto had complete faith in his recommendations. Her interviews with the candidates were based on the reports submitted by Mughal," shares a colleague.

In terms of his personal life, Mughal lived a very modest life making it very clear on his seven children (the eldest is 30 and the youngest is 20) that he will not extract any benefits from his position and influence in the party, nor would he cater to any of their materialistic demands. "All of us studied on scholarships from school to university, and travelled by public transport all our lives. He was obsessed with our education and made every effort to ensure that all of us earn a degree from good institutions," shares his daughter Hira Mughal. His modest means did not allow him to pay for a very expensive treatment. After KESC withdrew his medical benefits, the Pakistan Peoples Party bore all expenses of his intensive treatment that also included visits to London.

The most important lesson from Mughal’s brief life enriched by a very strong political struggle is his belief in the power of the democratic process. His whole life is a testament of the strength of this belief. The democratic process may be slow, tiresome, full of small and big setbacks and bitter experiences, but this is the only way a gigantic corporation, despite its best PR machinery, cannot hide the blot of unfair practices against its workers, or a political party, despite earning the label of a non democratic leadership, has been unable to shed the practice of workers’ consultation and representation. It is people like Latif Mughal who, with their silent but very effective contribution, ensure that that despite multiple attacks, democracy remains the reality of Pakistan.