How are blasphemy trials conducted? Challenges for the accused, lawyers, and judges

A man was suspected of committing blasphemy. Under the law, he was arrested and presented in a lower court, which convicted him. A few years and appeals later, a higher court citing a lack proof of intention acquitted him. Another man, one who found this judgment dissatisfying, shot the accused-but-acquitted man dead. The second man, the murderer, was then arrested, tried, and found innocent.

This story is from the British India of late 1920s. But today, the impact of the law in Pakistan seems unchanged. Although the blasphemy law is used much more frequently now (to settle land disputes, personal scores, and political grievances), the pattern of lower courts convicting and higher courts acquitting is the same: in over 80 per cent of reported cases, the accused are acquitted on appeal, according to the International Commission of Jurists’ (ICJ) 2015 report.

Other facts about the blasphemy cases that remain unaffected are that the cases still last for several years, and that accusations equate to death sentences, whether by courts, or commoners.

There are, however, some stark differences as well. One is the fact that back in British India of the late 1920s, Mahashe Rajpal, the man accused of publishing blasphemous content, spent more time out on bail than inside jail. Today, the accused are rarely granted bail. In fact, citing security concerns, the accused are mostly locked in solitary confinement.

A majority of blasphemy offences (295-A, 295-B, 295-C, 298-B, 298-C) are ‘non-bailable’ offences, which means it’s the court’s decision to grant bail. So, why doesn’t it? One reason may be that the accused is treated as criminals right at the outset, and the attitudes of the Investigating Officers (IO), lawyers, and even judges all play a part in regarding the accused as criminals.

Read also: Condemned either way

Even in dire cases, such as that of Tahir Iqbal who was paralysed waist down at the time of accusation and arrest, bail is not granted. (Iqbal was later found dead, allegedly poisoned, in Kot Lakhpat in 1992 while his trial was still on-going.) His lawyer, Naeem Shakir, says Iqbal was not even granted the courtesy of a wheelchair while in jail.

"This dehumanisation of those accused for blasphemy starts the day the accusation is made," says Shakir, one of the handful of lawyers in the country who take on the defence of the blasphemy-accused. "Right from the start, the accused is treated as someone who has committed the most heinous crime, and on day one the Investigating Officer declares a guilty verdict."

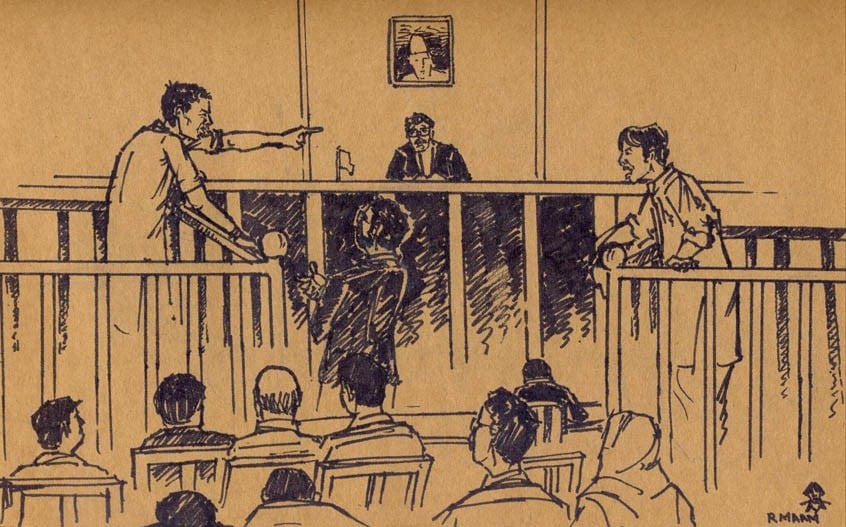

Once the hearings start, the atmosphere of fear surrounding the case and the accused only builds further. The walk from the gates of the court to the courtroom is terrifying. "You often have to walk through long lines of clergymen and their supporters, chanting verses and slogans at you and the accused," says Shakir.

Everyone in the courtroom adds to this air of terror by being hostile; the courtroom staff makes unnecessary remarks, the prosecution is often violent and aggressive towards the accused and their lawyer. "At Asia Bibi’s recent high-profile blasphemy appeal, while the court was settling down, lawyers accompanying the prosecutor were loudly reciting verses of the Quran, while standing a mere four feet away from the judge," adds Shakir.

The audience in courtrooms hearing blasphemy cases also adds to the fear. In trial courts, often one-third and sometimes up to two-third of the audience comprises supporters of local clergymen who is against the accused; or as in the case of Asia Bibi’s trial, the audience comprised heavily of members of Khatam-e-Nabuwat, a group headed by Ghulam Mustafa Chaudhry, the head lawyer for the complainant against Aasia bibi. "Often, these people stand up to make their presence felt, to show their strength in numbers, to intimidate the judges, lawyers and the accused," says Shakir.

"This kind of climate inside and outside courtroom directly influences the court and does not result in a fair trial or a just administration of justice," he adds. The right to a fair trial was included as a fundamental right in the Constitution in 2010, as part of the 18th Amendment.

This carefully constructed climate of fear disrupts other aspects of the case as well, such as the fact that the blasphemous statement under question can often not be repeated or discussed. "There have been cases when the defence has repeated the statement and been accused of blasphemy, so the route the counsel takes is to prove that the accused didn’t say anything, rather than prove that the statement was not blasphemous," says Reema Omer, a legal adviser for International Commission of Jurists (ICJ).

As for the attitudes of the judges themselves, Shakir says that "even if they are secretly sympathetic to the accused, their facial expressions, tone and body language all outwardly express disgust and disdain for the accused." They, after all, are also under a lot of pressure. Omer says judges often complain that as soon as a blasphemy case starts, they start receiving letters and calls threatening them and their children.

Lastly, judgments of blasphemy cases, even those in which the accused is declared not guilty give the impression that falsely accusing people for blasphemy is not something that deserves punishment.

In a 2002 case, a court found that an office-bearer of the Pakistan Sunni Tehreek, a religious organisation, had turned a dispute between two neighbours into a criminal complaint under section 295-C of the Penal Code for "his own ulterior motives and reasons".

The ICJ report cites that instead of directing the authorities to take action against witnesses who had committed perjury to frame the accused, the Court concluded its judgment with a prayer: "We pray that God give them wisdom to understand and appreciate what is ordained and to take care in future … Otherwise, mischief will always overwhelm and Satan will take us astray."

"The point is that instead of telling the police to lodge a complaint against those who made the false allegation, the judge turns to prayer," says Omer. "They are always trying to end these cases, or pass it over to the next judge." This may be either because they empathise/sympathise with the complainant or because of their own religious passion, or because of fear and pressure. Whatever the reason may be, in the current atmosphere the odds of a fair trial and just administration of justice are low.