The Koh-i-Noor is not just a diamond but the story of experiences and a projection of aspirations

It is a hotly debated issue. India wants it. Pakistan under Z.A. Bhutto first claimed it. Afghanistan under the Taliban wanted it. Even within India, there are competing claims. Andhra Pradesh claims it was extracted from its region. The famed Jagannath temple in Odisha exerts its right over it saying it was the dying wish of Maharaja Ranjit Singh to offer the diamond to the temple, not honoured by his descendants. The Sikhs claim that since Maharaja Ranjit Singh was the head of the Khalsa Empire, the diamond should come to Amritsar.

England, on the other hand, has completely refused to even acknowledge the demand. It was a gift by the sovereign it replies, a gift they forced out of the boy king when they also usurped his kingdom, they fail to mention. The former British Prime Minister David Cameron when asked about the diamond responded, "If you say yes to one you suddenly find the British Museum would be empty". There are today at least 89 diamonds in the world, larger than the Koh-i-Noor but no other jewel matches its symbolic value.

In contemporary world politics, the diamond underscores debates about colonisation and repatriation. It raises questions about modern nation states and their connections with their ancient past. For South Asia particularly, it brings to focus Partition and the unequal distribution of resources. Within Pakistan, in order to claim the diamond, the state needs to confront the issue of its non-Muslim heritage and its status in a Muslim country. The debate about the diamond raises far more questions, about its rightful heir, true origin, than correcting historical injustices.

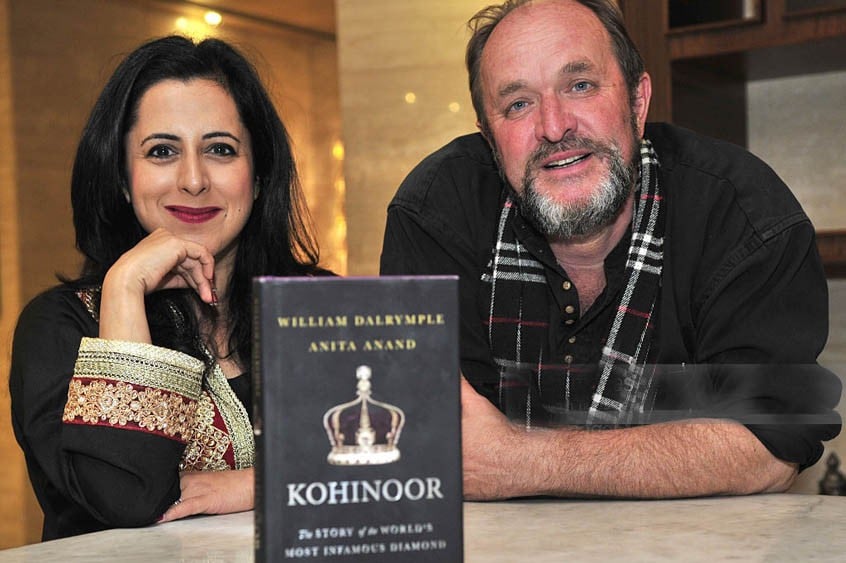

It is in this context the recent book Kohinoor by William Dalrymple and Anita Anand attempts to answer these uncomfortable questions, bringing several communities and countries to the brink of rhetorical war. Perhaps by tracing the history of the diamond to its ancient past, one can decide once and for all who does the diamond actually belong to? However the book doesn’t answer any such question. Right at the start it acknowledges the known history of the diamond, beginning from the Peacock Throne of Shahjahan in the 17th century. The story of it being extracted from Andhra Pradesh or coming from the sun god are all conjectures, Dalrymple identifies.

Once the British extracted the diamond, Thomas Theophilus Metcalfe, an official of the East India Company, was assigned the task of tracing back the history of the diamond. Thus began a process of orientalism -- of infusing history with mythology, of romanticising the past of this ancient land, in the process exalting the virtue of the occident, the coloniser, with the prowess to harness the energy of an ancient mystical land. Recording tales from the streets of Delhi and mixing it with his own fancy, Metcalfe came up with the "history" of the diamond. This "history" is now acknowledged as authentic history of the diamond, the basis of several of the claims mentioned above.

The Kohinoor, by the time Metcalfe was assigned to trace its history, had become an imperial symbol. It had adorned the fabled Peacock Throne of Shahjahan at the zenith of the Mughal Empire. Its occupation by Nader Shah represented the downfall of the Mughal Empire. Ahmad Shah Abdali secured the diamond for himself, marking the beginning of the Afghan Empire. Ranjit Singh brought back the diamond to India. Tied to his arm, like it had earlier been tied to the arms of Ahmad Shah Abdali and Nader Shah, the diamond became a symbol of imperial authority.

Punjab remained the final frontier for the British, its annexation therefore represented the colonisation of the entire Indian peninsula. For the newly rulers too, like others before them, the diamond symbolised Imperial authority. It was therefore essential for such an important diamond to have a grand symbolic history. But none was to be found in Mughal records. There were mentions of large stones as Dalrymple mentions but none specifying Koh-i-Noor. A story, therefore, had to be crafted to fit the stature of the diamond. In order to highlight the significance of the latest acquisition of the British, it was imperative to throw back the history of the diamond in the darkness of mythology. A great past colonised and possessed by the coloniser, a great empire.

Written by two authors, the book is actually two little books, each with a distinct flavour. Dalrymple true to his writing style provides us with a context. This part is not a history of the diamond, but rather a history of diamonds in Mughal India and before that. This context is essential, for only then the true essence of the contemporary story comes to light.

He talks about the mythological and political significance of diamonds, attitudes that continue to shape our contemporary perception of Koh-i-Noor. He identifies how the increasing significance of the diamond in the past two centuries represents the changing attitudes in society. The British as opposed to the Mughals preferred diamonds over rubies; hence explaining the importance given to Koh-i-Noor. In the Mughal court, a ruby of equal size to a diamond would have been preferred over the latter.

Having established the context, the second author, picks up the thread of the conversation from where it had been left. Anita Anand, a British-Sikh, is the author of the book Sophia, the granddaughter of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Her expertise in Sikh history makes her the perfect candidate to pen the story of Koh-i-Noor.

The story of Koh-i-Noor is the story of the rise of Ranjit Singh, but also the fall of the Sikh Empire. It is the story of Duleep Singh, the last maharaja of Punjab, who moved to Britain and eventually died penniless. The story of Koh-i-Noor is also the story of Victorian England, of a great empire, showcasing its strength to not only itself but rest of the world.

The Koh-i-Noor is not just a diamond but the story of experiences and a projection of aspirations. It is what its beholder wants it to be. It is the ultimate symbol and this book is an important step to demystify this symbol.