American laureate William Faulkner (1897-1964) in his novel, Requiem for a Nun, expounded that "the past is never dead. In fact, it is not even past".

Faulkner was expressing a sentiment all too familiar to scholars who study how history matters in the world of politics: the sentiment that however much we value political novelty, what we classify as political change masks deeper underlying continuities with the past.

As Karl Marx noted in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, "the tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living."

In fact, Faulkner and Marx tap only half of the issue, for it is also the case that what we think of as political continuity masks deeper underlying change. The writer David Lowenthal eloquently captures this idea: "living in ever new configurations of nature and culture, we must think and act de novo even to survive; change is as inescapable as tradition." The more things change, the more they stay the same; the more they stay the same, the more they change.

Historical continuity and discontinuity being simultaneously present appears paradoxical. It is implicitly acknowledged but less appreciated, especially (but not exclusively) among social scientists. This simultaneity is at the root of the debate over whether history can repeat itself, and of distinctions between "good" and "bad" historical analogies. After shrugging off the theoretical debates about the long duree history, we need to bring in ‘the legacy’ as an epistemic category and try to establish its link with history as a repository of ‘the past’ human experience.

Before going any further into this column, it will be worthwhile to define legacy.

In historical terms, "a legacy is something that is handed down from one period of time to another. A historical legacy can be counted as a good thing or a bad thing. For example, the invention of the wheel (for carts, as a potter’s wheel, as a millstone to help turn grain into flour, and as an early water wheel) in Mesopotamia can be seen as something good. The development of slavery is a bad legacy." But instead of going into the argument of a good legacy or a bad legacy I would concur with Jim Rohn when he says, "All good men and women must take responsibility to create legacies that will take the next generation to a level we could only imagine."

That is what matters to us in the prevailing context of Pakistan, where leaving a legacy is, in most cases, not considered worth bothering about. But we will come to that point a bit later. We should revert to unravel the connection that history, legacy and tradition have and how they complement each other. Legacy, tradition, and history are inter-connected and inter-dependent after all.

The whole debate of ‘tradition’ and ‘change’ or ‘continuity’ and ‘discontinuity’ attains a significant measure of clarity if focused on the connection that legacy has with history. Legacy accords perpetuity to history because the former is a phenomenon in which the footprints of the latter are conserved.

Thus ‘legacy’ is essentially history’s resonance in the present. More often than not, legacy articulates itself to a substantial extent in the form of ‘tradition’, which works as a foundation for any society to build itself on. Every society (or polity) authenticates itself by resorting to ‘tradition’; therefore it is the anchoring force which holds the disparate elements within the collective together.

My assertion here is that tradition is predicated on legacy which in turn is embedded in the history of a nation. It is the legacy in particular which we (Pakistanis) do not generally care about. One thing that is important to underline is the agency of a historian to write history which conjures up legacy, and it is legacy in turn that expresses itself in the form of tradition.

The plight of historians being as deplorable as it is in Pakistan, no proper training or support being available, history in such circumstances cannot sensitise people about the value and significance of the legacy. All it adds up to is the practice of history-writing which is of the essence here. Thus the relationship of people with history and the consciousness that it generates becomes weak.

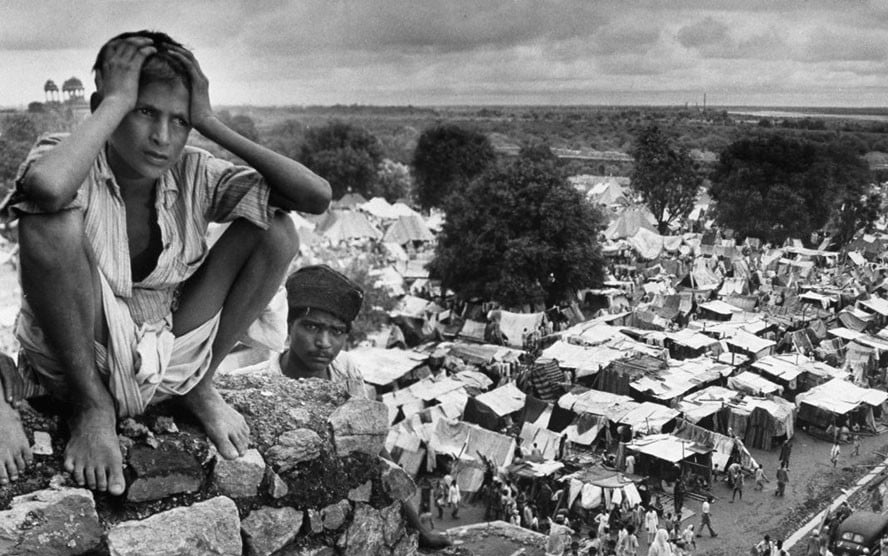

As a consequence, social myopia sets in and gives rise to the general insouciance towards leaving any meaningful legacy for posterity to follow. The legacy left by the first generation after independence has dissipated in the air; hence it is nowhere to found in a tangible form. That is the fundamental reason for institutions and institutionalised practices having failed to strike roots in Pakistan. Resultantly, long-term planning is a path that our policy makers have feared to tread. Ad-hocism is a cherished practice here, due to which the problems and challenges faced by the nation cannot be resolved.

The problems are deferred and not addressed. Now that colonial structures have run out of their relevance, some creative solution to the issues of governance, education and health care are needed.

In the absence of legacy which manifests itself in tradition, any concrete measures to sort out the existing mess seem highly unlikely. I solemnly believe that ‘history’, ‘legacy’ and ‘tradition’ ought to be made sense of, in academic terms. Their connection and mutuality are to be understood afresh and debated in the academic circles, so that our being and existence come to rest on solid and surer foundations.

It is high time to raise such fundamental questions. I will conclude this piece with a quote by John Allston, "the only thing you take with you when you are gone is what you leave behind". I think in this quote, there is a clear message for our policy makers.