Mumtaz Ali’s book tore through many taboos within Islamic law by its radical content

"A common argument used to justify the false superiority of men over women is that there has never been a female Prophet - this is used to imply that Allah considers men to be morally and spiritually superior to women. However, Allah sent a total of 1, 24000 prophets out of which we are aware of the life stories of no more than 20. How do we know that many of them were not women (Prophetesses)? … Such arguments are nothing more than bogus attempts to conceal the fact that the Sharia considers men and women to be equal."

The above passage has a remarkably contemporary ring to it but is actually taken from a text written in the late 1890s. One would also assume that its author was someone with a liberal, western education but what is astonishing is that it was written by a Deobandi cleric deeply rooted in Islamic education. In fact, so radical was the text’s message of absolute equality between genders that upon reading the manuscript Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, by no means a traditionalist, tore it to bits and urged its young author not to publish it. Since Sir Syed had already faced the wrath of conservative ulema, he feared that the book’s radical content, particularly its advocacy of women’s education, would stir up a storm and undermine his efforts for men’s education in the Muslim community.

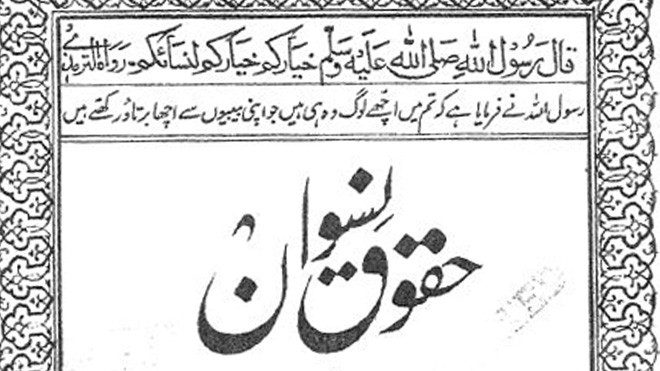

The book in question titled Huqooq-un-Niswan (Rights of women) is a defense of women’s rights in Islam and was only published in 1898 after the death of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. Its author, Maulvi Sayyid Mumtaz Ali became better known through the Lahore-based publication of a women’s magazine called Tehzib-un-Niswan (Culture of women). The editor of Tehzib-un-Niswan, Muhammadi Begum, was his second wife and the magazine became famous for its radical positions as well as for publishing the literary work of writers such as Atiya Fyze, Zehra Begum and Nazre Sajjad, the mother of the legendary Qurratulain Hyder and an accomplished writer herself. Till his death in 1935, Mumtaz Ali periodically wrote articles in defense of women’s rights in the magazine but Huqooq-un-Niswan, though largely ignored, remains his most powerful work.

How did a Deobandi scholar with little ‘modern’ education end up as a champion of equality at a time when even modernists like Sir Syed were not keen on it? The answer, according to Gail Minault, a professor of Islamic History at the University of Texas, Austin stems from his keen awareness of the need for internal reform within the Muslim community and a belief that greater gender equality would be essential in achieving this goal.

A product of the munazara (religious disputation) culture where scholars of different religions and sects would engage in public debates, Mumtaz Ali’s specific interest in gender equality began in response to the accusation by Christian missionaries that Islam gave a low status to women and this was why Muslim women remained uneducated. He believed that the status of women in Islamic law was theoretically higher than what the patriarchal society was willing to allow. Like other Muslim reformers (though nowhere near as radical as him) he explained the existence of such attitudes through custom and tradition and a lack of understanding of Islam’s ‘true spirit’. Huqooq-un-Niswan is the outcome of his attempts to combat such attitudes and to argue for a case for women’s rights based on Islamic precepts.

The 190-page monograph is organised into five parts: 1) Justifications used to assert the superiority of men over women, 2) Women’s education, 3) Purdah, 4) Marriage, 5) Relations between husband and wife. The structure of each section is clear, with the justifications listed in the beginning that are then systematically countered using a combination of Quranic and Hadith sources, different schools of Islamic law and equally importantly, a thorough knowledge of social customs as well as Aristotelian logic. The overall aim of the text is to dismantle what Mumtaz Ali calls "mardon ki jhooti fazeelat", i.e. the false superiority of men over women.

The rigorous and logical style of presentation and argumentation is combined with an excellent use of irony and humour, reflecting the influence of munazara on his writing style -- for example, in response to the commonly used argument that men are physically stronger than women and therefore superior he replies that donkeys are stronger than men so by that same logic we should also conclude that the former are superior to the latter. Or against the argument that Allah created Adam first and Eve after him which proves the former’s superiority he states that one could just as easily argue that Allah did not want women to be alone and so for her companionship He created men first.

But more important than the style of the text is its radical content in which Mumtaz Ali tears through the many taboos within Islamic law and Muslim society; for example, his claim that women’s testimony is half of a man’s only in matters of business where they have less experience but then insisting that this reflects their economic marginalisation not some inherent defect, the implication being that with greater inclusion this law itself can be changed.

This spirit of equality of opportunity runs throughout the text, from matters of education where he wants to see women given the same education as men, to marriage and dress codes, where he wants modesty to apply to both men and women and not simply be forced upon one.

In the introduction, Mumtaz Ali wrote that he knows he would be attacked by people blinded by their adherence to false customs and that he is prepared to face their wrath and stand for what he believes to be the true spirit of Islam. Unfortunately for him, his tour de force was met by something worse than hostility - apathy. His own publication house in Lahore published the book which sold a few dozen copies after which it was never republished until the late 2000s when Asghar Ali Engineer, the late Indian Muslim reformer obtained a copy from a US library and published it.

Read also: Re-imagining of Muslim Women - II

In 1898, the book and its author were miles ahead of the times but in today’s Pakistan where women are outnumbering and outperforming men in higher education but continue to face all sorts of opposition from patriarchal society and religious obscurantism, the time may finally have arrived for a new generation to discover this revolutionary text and its remarkable author.