Many years ago, as an art student travelling in a bus, I had carelessly put my feet on a dirty rough sack lying close-by. My fellow passenger instructed me to remove my shoes from his bag which contained tools he used to earn his bread. This encounter made me realise the worth of instruments of one’s profession, whether it’s breaking bricks on a construction site or creating profound works on canvases.

Like the tools, the place of work is equally important for a creative individual. Looking at artworks in a gallery space or in a collector’s residence, one can’t understand the relationship between the artists’ studios and their activity and how environment and physical location impact the way artists think and approach their artwork.

Prior to this modern notion of an artist being a solitary worker busy in his space, painters and sculptors used to work in their workshops along with fellow artists and apprentices. Whether those were karkhanas of Mughal miniaturists or ateliers of Renaissance painters and sculptors, works were created involving others so that the commission of the patron (Emperor, Pope, prince, merchant etc.) could be completed through collective effort. Large-scale paintings, huge sculptures and intricate miniatures were possible only because many people working on them, sometimes without even the name of the main artist.

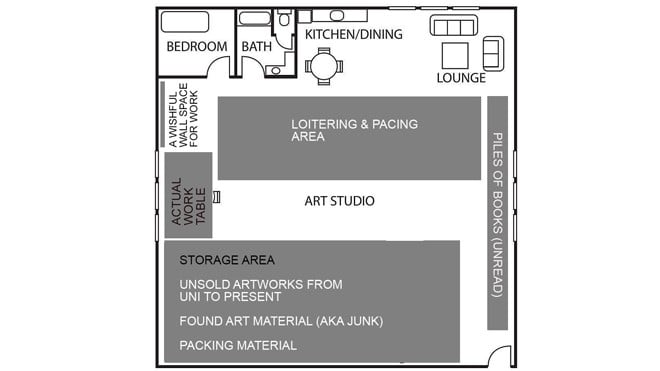

It is only in the modern age that the person of the artist has come into such sharp focus, styles are revered, and the work is exhibited in galleries. Subsequently, a barrier between the artist and society has emerged and along with it complaints and criticism of not comprehending the works of art. The individuality and independence of an artist has led to the seclusion and sacredness of studio space: it’s a private world, almost an extension of one’s mind, in which others are either not allowed or are unable to enter.

I recall interviewing Jamil Naqsh several years ago. When I expressed my wish to see his studio, he pointed to a collector of his works and said: "She has been coming to my house for the last thirty years. Ask her if she ever was allowed to go upstairs where I paint. That place is just for me, for my models and my birds."

Yet at times we are able to glimpse the artist and his work environment. One of the most representative photographs of an artist in his studio is of Francis Bacon, the British painter. According to Barbara Dawson, "The chaos of his studio became famous. Vying for floor space amid the boxes and slashed canvases were art catalogues, hundred of photographs, creased and torn, books on wildlife, male anatomy, cricket, Egyptian sculptures and the supernatural". The clustered atmosphere of his studio is a reflection of the artist’s approach when he disfigures the faces of his subjects. At the same time, a lot of architectural spaces in his paintings are clearly planned and neatly composed. So what we witness in his real space is in direct contrast to his pictorial space.

There are other examples of artists’ studios where they are engaged in making of their sculptures (Alberto Giacometti), daubing big canvases (Willem de Kooning) or merely sitting in the space reflecting. But somehow the space in which an artist works is linked to his imagery and aesthetic choices. To start with, the decision of his art piece’s scale depends upon the dimension of work place. Light, location and other facilities also contribute or conflict with the artistic practice and production.

Sometimes the space leads to certain kind of artworks or one’s creative necessities demand a specific working area. American Pop artist James Rosenquist’s studio in Florida was situated inside the hanger for aeroplanes. His enormous paintings were possible only in that space, whereas a person like Kurt Schwitters understandably did not require a large room to make his small collages. Iqbal Geoffrey creates innumerable mixed media on paper and collages from his lawyer’s office near the Lahore High Court.

The main question for an artist, art historian and critic is: how much does a studio’s physicality impact on the artist’s production, or if it really matters? Does an artist’s style and imagery have a role in shaping the studio arrangements?

Here in Pakistan, some of artists’ work places are rooms in their family houses, private small flats, or large areas with a few studio assistants and helpers. All this is a new phenomenon because many of our masters painted in their bedrooms, living spaces, abandoned bathrooms, and narrow corridors. The physical lack of studio spaces for many painters could be a possible explanation for the popularity of landscape painting in Punjab. More recently, artists have separated their living quarters from their work areas and both are sometimes miles apart.

In an interesting scheme, our contemporary artists have reverted to Renaissance and medieval tradition of studio being a workshop with several hands around. Rashid Rana’s studio is an example, and so is Adeela Suleman’s studio in Karachi -- echoing the Factory of Andy Warhol and huge space of Anselm Kiefer, which is spread and functions like a big factory. Recent years have witnessed young graduates from art school in search of studios and sharing these with their contemporaries.

Like the increasing numbers of galleries served to develop a professional attitude among artists, the rise of studio spaces for artists has also changed the art of this country. Now if a person is paying monthly rent to pay for his work space, what is produced is not just an exercise in personal and private delight but pieces created with a lot of consideration and meditation.

Even if an artist does not produce work every day, the studio like his/her imaginative self is significant. It is a place where ideas develop, new imagery evolves and unexpected forms emerge. Artists can identify with Israeli author Amos Oz, who in an interview disclosed how he goes to his (writer’s) studio for eight hours every day, and stays there whether he writes or not because like a shopkeeper he has to be at his shop and wait for customers (ideas in his case). On a good day, they will come but you have to be available on all other days too. No one knows what day turns out to be successful.