The recent works of Saba Khan at Rohtas 2 contain strong political and societal connotations of popular images

Even though both ‘pop’ and ‘popular’ seem closely connected, there is a difference between the two words in our context, in terms of music and objects. And once translated into art, these become binary genres -- of ‘Pop Art’ and ‘Popular Art’. The former is a school in the canon of art history whereas the latter is a collection of various products prepared by the untrained hand, and is a residue of bad taste. The latter usually indicates the lower class that is not educated, yet is not shy of expressing itself.

The popular imagery present in our midst was never acknowledged as art, till its potential was discovered by a group of artists working in Karachi in the early 1990s, and subsequently emerged as a major movement in the local art.

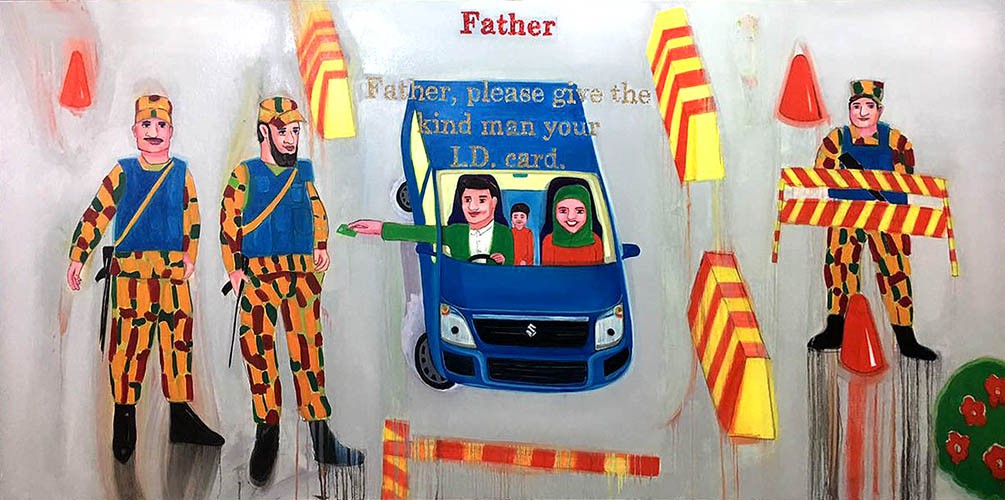

Its gaudy appearance apart, there are strong political and societal connotations of these popular images. In her recent works, Saba Khan focuses not just on the pictorial sides of popular forms but also comments and critiques on practices beyond the aesthetic sphere.

Her new paintings created in oil and with beads (along with one that consists of flickering LED lights) embody the general idea of decorativeness and beauty, hence spiritual salvation. People try to transform their living place into a reflection of Eden where food, shelter, comfort and pleasure are provided to their family; apart from the basic necessities, the house must look ‘pretty’. The notions of beauty range from elegant and minimal to kitsch and extravagant.

Intriguingly, in recent times, popular taste is the triumphant voice, visible everywhere. From national monuments, commemorative plaques, public parks and big malls to private houses, small shops and places of worship, one comes across structures or artefacts that represent the taste of the larger community. Incorporating these ‘unavoidable’ visuals in her art, Saba Khan constructs a chronicle of our times. This includes our attitude towards faith and our yearning for better living.

The elements of her pictorial language are derived from multiple sources. Painting on public transport, page from a school primer, hoarding for beauty treatment, fountains on roadsides, cakes, parts of packed meat, portions of fast food, and views of a newly built middle class house complete a narrative that conveys how the majority of our public thinks or likes to think, and their aspirations towards ideal life.

Saba Khan probes these segments of popular sensibility further by linking them to larger political conditions of our country. For example ‘Father’, that seems an illustration from a kid’s textbook, is the scene of a family (with wife in green hijab) being stopped by security forces next to various kinds of barricades. In ‘Hilal Dreams’, immaculately rendered portions of chicken with skin are arranged on a plastic tray with outlines of roses on four corners and two strings of prayer beads on both sides. Both works reveal how the power of religion is shaping our life and affecting our surroundings. The rise in religious zeal is depicted in her rendering of sliced meat with prayer beads, referring to the beheading of infidel hostages by faithful militants.

Besides erecting the edifices of state power and commercial aesthetics in various paintings, Khan punctures them too. For example, drawing the outlines of a fountain in elementary manner (almost by an untrained hand), delineating trickling water in thin lines; or inducting a line from social media ‘hi, do you want to friend with me’ in Urdu script in the middle of silver-grey plate of the plaque where usually the name of dignitary who has inaugurated the project is inscribed.

The questions of power, identity and public taste are invoked in her works, and indicate that all of these are interconnected. The consumption of commodities emerges in fondness for food, hence the outlines of ketchup and burgers next to the name ‘Vicky’ or a big cake in the middle of a standard ‘romantic’ landscape replicating a truck or rickshaw painting.

In her new body of eight works, her content is as enthralling as her ability of image-making. Regardless of whether it is oil paint in thick coats or thin layers, beads in single tones or sequins in gradual shades, the painterly ability of Saba Khan is at her best in these works, particularly where she demonstrates her command in diverse visual dictions, occasionally combining them.

The decision to incorporate multiple styles and vocabularies affirms the artist’s maturity of vision, mastery of medium and confidence in her craft. Her latest works in their formal diction are clearly distinct from her previous paintings even though her concerns come from similar sources. This aspect of taking risk and accepting challenge is an unusual, rather amazing, feature of her art which is about private and public realms converging in a personal entity. Like her solo exhibition How Not to be Small and Silent in which the entire format of display -- with fake marble treatment on gallery walls and plastic plants -- creates a curious commodity we call ideal (or industrial) world that we dream and desire but may not deserve.