The Lahore Museum awaits the attention of concerned authorities that aren’t able to carry out the restoration of the building as well as the artefacts it houses, efficiently and cost-effectively

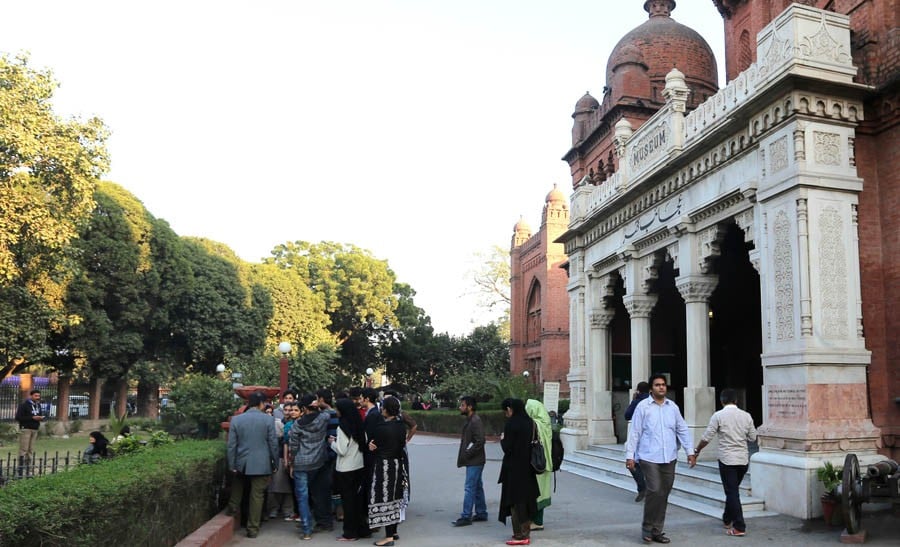

For well over a century, the historic red, ‘exposed’ brick building of the Lahore Museum has sat majestically on the city’s famous Mall Road. Designed by the well-known engineer and philanthropist Sir Ganga Ram in late 1800s, the Museum is the biggest in the entire country. Sadly, however, the place has been in a constant state of neglect; the concerned authorities not being able to carry out the restoration of both the building and the artefacts it houses, efficiently and cost-effectively.

As a result, the Museum is losing its appeal for the public -- something which is more than apparent from the diminishing numbers of visitors it receives.

What is even sadder is the fact that despite its impressive collection of pieces that date back to the Gandhara period, there is a general disregard for history and also for the paintings, sculptures, and other artefacts that are placed here.

The Lahore Museum appears quite sombre and rather unattractive. It is said that under the regime of its former director, there was an increased effort to allow in more natural light by opening up windows and adding skylights. Again, this has done little to add to the ambience of the place.

Dr Iqbal Bhutta, Director, Archeology, Pakistan Railways, is known to have regarded the years -- from 1970 to 1990 -- as the "golden period" of the museum. This was during the times of Dr Saif-ur-Rehman Dar, a "renowned scholar, a professional archaeologist, and a museologist with very good skills and knowledge about the museum, who also contributed a number of books about… the problems the museum faced."

This "golden period" was supplemented by B.A. Qureshi, another important figure in the recent administration of the museum, who was Chairman, Board of Governor, for the Lahore Museum back then.

More recently, the museum deteriorated into a state where it has not been able to pull itself out of, entirely. The situation remains to this day. The reasons cited are many: a lack of support or interest in the restoration process, the preservation of the museum and its pieces.

The famous Sadequain mural that had long graced the ceiling of the museum hall is another example of the neglect the place has been subjected to. The mural had been slowly coming off because of poor maintenance.

It has been nearly three years since the Sadequain mural was taken off in an effort to restore it to its original grandeur, but so far no definite time period has been assigned to the completion of the task.

The visitors’ engagement suffers also because of a lack of signage. This aspect needs the urgent attention of the authorities. Boards and signages that provide detailed, albeit precise, information on the pieces displayed, should be added. The information should be provided in both Urdu and English languages, for the facility of the foreign visitors.

Renowned artist Aijaz Anwar calls the treatment of the art pieces in the museum as "zulm" (torture).

Talking exclusively to TNS, he says that it is due to a lack of awareness of different aspects that has caused the art pieces to lose their original sheen. "Awareness is stronger than the law," he declares, referring obviously to the bureaucratic red tape that often causes the lesser officials to back off when they are trying to introduce positive changes.

Anwar gives the example of the type of lighting that has been used in showcases holding the paintings. "This can damage the paintings," he says, "and fade the colours."

He would like the motion sensor lights to be installed, as these shall help to save electricity and also expose the art pieces to minimum amount of light.

He regrets that there is a lack of experts and trained carers at the museum. "Those working in the museum should be qualified in subjects like museology and archaeology, so that they can handle delicate materials.

"The harsh reality is that it is not possible for most people to acquire such qualifications as these are available only in foreign countries such as the UK. Consequently, the workers are trained on-the-job. Their output is meagre, compared to the level of excellence we find among those working in different museums of the world."

Aijaz Anwar blames it on the bad decisions that are taken by an "incompetent board" that boasts no experts on matters related to museology, archaeology, and the art of preservation and restoration of artefacts.

A recently retired director of the museum, Sumaira Samad strongly rejects the allegation, saying that the people on the board are "a good mix!"

About the issue of lighting, Samad says she launched a drive during her term as director, to swap some of the lights with the LEDs as the latter do not give off ultraviolet radiation and are better for museums.

As we see in the UK, for instance, the museums are attached to different arts institutions, the Lahore Museum was also initially a part of the Mayo School of Industrial Arts (which later came to be known as National College of Arts). The two were situated adjacent to each other. Its first curator was Lockwood Kipling, an English arts teacher and illustrator, who was also the first principal of the college in 1875.

Recently, there has been talk of re-joining NCA with the museum. Samad believes merging the two will "only distract both institutions from their original mandate rather than achieve anything material in terms of expansion and restoration. The two should therefore, focus on building linkages and forging collaborations."

"In my time, efforts were made to restore not just the museum building, which in its own right is a historical marvel, but also the art pieces that are placed inside," she claims. "This required re-working the store rooms that housed the spare pieces as well as the originals from many exhibitions.

"It is an accepted practice around the world that imitations are placed in display cabinets and the originals in the vaults. This ensures that no piece is damaged."

This also helps in the event of a theft, something the Lahore Museum is no stranger to. The museum no longer boasts a collection of coins and medals. As per the management, space was needed to create more room for spare and unused pieces. The loss of the exhibition, however small, sets an uneasy precedence for the management and the museum to do away with any such events that play an equally important role in generating public interest in the museum.

The museum seems to lacks an interaction with its visitors. Perhaps, an interactive screen that would allow you to delve into the history surrounding a particular piece or exhibit would prove to be a stepping stone towards increasing the public perception about the place.

The building itself holds a great potential. To quote Sumaira Samad, "It was purpose-built to be a museum." Its prominent features include the high ceilings that ensure that the floor stays cool during the lethal summer months of Lahore.

On the other hand, an increase in the termites in the crevices of the showcases needs to be countered immediately.

The Lahore Museum has made certain strides towards building its name as an institution of international repute, but largely, it has fallen short. Reportedly, the management has been involved in loaning some of their pieces to museums around the globe for temporary exhibitions in return for monetary compensations. The government must step in to help the situation.

We hear of a project funded by the Government of Punjab, called ‘Development and Upgradation of the Lahore Museum Building and Conservation Facilities.’ Under this project, the museum has "hired more research officers, restoration and exhibition officers, and chemists so that there are more people to look after such a big place," says Samad.

After a day spent roaming the halls of the Lahore Museum, I exited with a greater sense of appreciation for the history surrounding us. The Museum, in all its glory and despite its imperfections, is one of the last few remainders of the past that we all share in this country and city. The site and the objects inside must be accorded their due import. The greatest downfall of a society happens when we are unable to preserve our ancestral roots throughout history and simply allow them to be lost with time due to our failure to act. Each and every citizen of the city must play a part in understanding the complexity of the issues surrounding the preservation process of a historical place like the Lahore Museum.