The tragedy and shock of the abducted social media activists should foreground and not obscure the meanings ‘the missing’ have taken on in our public life and discourse

I have seen lines from Faiz’s poem Nisar main teri galiyon ke quoted to give voice to the helplessness of some who are protesting the abductions. But, in that poem, even though the speaker watches out furtively for his body and life -- nazar churaā ke chale jism o jaañ bachaā ke chale -- he sounds sure of speaking to others like himself from this side of the bars. It’s a hopeful song of imprisonment, seeing its own condition as one of separation from the romanticised watan whose evenings and mornings he continues to decipher and imagine -- chamak uThe haiñ salasil to ham ne jaanaā hai -- from the darkening and illumination of his prison cell. There is a connection between the other world and his prison netherworld, and his ‘ahd-e-vafaā’, keeping of faith, sounds sure of being heard in that other world.

The confidence of being heard, in its fear and hope, is what I hear in the poem.

Salman Haider’s chilling words in Safhe se Baher Ek Nazm are completely outside the frame of this redeeming prisonhouse. Unfathomable distance away from Faiz’s words, he speaks not of stealing away his body in fear like his compatriots who observe the custom of the land, but of disappearing like others, like others becoming a file that will be taken to court, or a photograph that his son will kiss for the journalist’s benefit, or the silence his wife will wear.

Reading these words, I think about the deathly if courageous resignation -- surely not the courage of defiance, of the voice raised against zulm in consort with others -- that it takes to repeat these words in one’s own voice. The poem imagines itself becoming inanimate, totally passive unless it leaves the page -- which it can leave not as lyric but only as crime: ‘Nazmon ka safhon se bahar nikalna jurm hai’.

This illuminates where we are now.

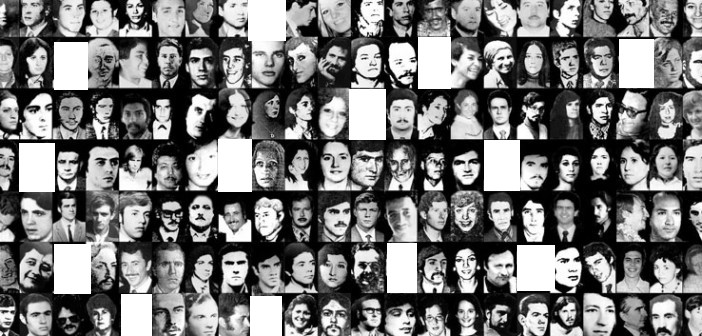

The ‘missing persons’ are not just individuals but versions of a death-text being written into various scenes of our common life. In each instance, it signifies a point beyond which we cannot go, cannot see what kind of gestures and figures vanished bodies and silenced voices will be able to make. This void becomes surrounded by hate-filled meanings read into these vanished lives and bodies.

Anti-nationalist? Anti-development? Anti-religion? Anti-anything-else? A number of accusations are enough to mark the absent body as always having deserved death. So that the fact of death -- which may or may not have happened, the doubt is never put to rest -- is irrelevant. What matters is that death, disappearance, is what necessarily needs to happen or to have happened to this body-become-void.

This is what terrifies: that what someone may have done will not matter, but what he or she can be interpreted or imagined as or rumoured to have done, the meanings fabricated around absent actions and bodies. What may someone not become, when the presence of the words and the body can no longer offer resistance? The hideous transformation of these missing people is engineered to show that the anomaly was that they were allowed to remain visible at all.

We probably are someone, or know someone, who is examining his or her existence and wondering if we are good enough subjects for such transformation. That there is randomness and chance here is clear, but still -- is there a pattern to our words, some excess or mark of distinction which can make them more likely to attract chance and randomness? And on and on it goes.

We probably also know someone who is interested in explaining this away in terms of the existential dilemma of the state. If the state were weak, it would have no choice but to put up with visibilities of different kinds that offer different scenes of resistant life. The strong state dominates our field of vision totally. Only a strong state has the power to make those others disappear whom the national interest has recently decided were mistakenly allowed to appear, and now merit erasure.

This move has had substantial traction. It was deliberately preceded by enough killing for the victims to become used to the logic of killing. The violence of enforced disappearances begins, much earlier than the abductions, in the sense that there is nothing to counter helplessness except unhindered strength.

Only a strong state can make certain people go away, and the repetition of the void of the ‘missing persons’ in different contexts -- political parties, insurgents, criminals, sectarian militants, state-supported militants, media activists and now social-media activists -- says that the state reckons that everyone is ready to accede in someone’s disappearance. Which is why a government minister does not bother to make even a token statement about due process when a sectarian terrorist is killed in an encounter. Instead, he shows incredulity that we are not grateful that someone has made the problem go away.

Not letting the void be colonised by hostile, hate-filled meanings seems the obvious thing to do, even as the fate of the missing anyone may become saps away courage and heroism from this effort. Beyond this, not much is clear as long as strong states and invisible bodies remained coupled in our political fictions.