Nur Ahmed Chishti and the notion of the ‘yadgar’

My column ‘All about Nostalgia’ that appeared on the Special Report pages a few weeks ago evoked several responses. One was from young scholars of History and English Literature. They complained about the euro-centric treatment of the subject, and that indigenous nostalgic impulses were taken up just tangentially.

The lingual and theoretical frame(s) was undoubtedly euro-centric, but the sentiment similar to nostalgia exists in every culture and society, and therefore transcends cultural or social specificity.

Instead of dismissing their response, I started looking at various sources to explore any synonymous formulation deployed by locals to express the same sentiment as nostalgia.

My conversation with a colleague, a cultural historian, Dr Hussain Ahmed Khan, opened a new vista, yadgar, a formulation that he inferred from Nur Ahmed Chishti’s (1829-67) monumental work, Tehqiqat-i-Chishti, in his widely reviewed book Artisans, Sufis, Shrines: Colonial Architecture in Nineteenth-Century Punjab. Yadgar, an expression of Urdu, is usually translated as ‘monument’ mostly in architectural connotation. But Chishti has given it a theoretical twist which brings it quite close to nostalgia in terms of its meaning.

To make sense of yadgar, the context of the age in which Chishti was born and lived warrants some light on it.

Nur Ahmed Chishti was born on June 10, 1829 in Lahore when Ranjit Singh was the ruler of Punjab. His was the family of Iranian extraction that had produced several generations of very good scholars and eminent sufis. Muharram Ali Chishti, who later founded the Rafique-i-Hind, a Lahore-based newspaper, was Nur Ahmed Chishti’s younger brother. Nur Ahmed took an oath of allegiance to a renowned Chishti Sufi Suleman Taunsvi, and Faizullah Sakin, another Sufi from district Karnal.

Therefore, his personality and overall disposition was tangibly overtaken by the sufi teachings and practices.

Chishti was quite young when Punjab descended into chaos and disorder in the wake of Ranjit Singh’s death in 1839. For 10 years the whole region witnessed turbulence and instability until the annexation of Punjab came to pass in 1849. It can be argued that it was because of the Sufi influences that Nur Ahmed kept his composure in an era that was strife torn.

Khan sees these influences in his writings too. In this day and age, when Pakistan has half sunk in the quagmire of sectarianism, it is important to note that Chishti never wore his sectarian identity on his sleeve. People kept speculating whether he was Sunni or Shia. It was only when someone pointedly asked about his sectarian allegiance that he revealed he adhered to the Sunni sect.

He completed his education in 1842 and started tutoring the sons of nobility. Not only Faqir Azizuddin’s sons got instruction from him but during the days of the British Raj, he taught Urdu, Farsi and Punjabi to around 2000 Englishmen. People like R.C. Temple, the author of The Legends of the Punjab, and once commissioner of Lahore was his tutee. Similarly Edward Thornton, Lord John Lawrence (Chief Commissioner of the Punjab and the first Lieutenant Governor of the Province) and C.U. Aitcheson (yet another Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab) received instruction from him. It was at the behest of several British officers that he set out to write the cultural history of Lahore, and some of them ‘reviewed his works in contemporary journals’.

In Tehqiqat-i-Chishti, Hussain Ahmed Khan states, "he imagined his ‘cultural identity’ by narrating the details of nineteenth-century monuments in Lahore." Chishti invoked the notion of yadgar while furnishing the details about old buildings. He lamented about the destruction of mosques, shrines and palaces during the Sikh rule. He catalogued buildings ravaged and plundered by the Sikhs, such as the shrine of Data Ganj Baksh, Khanqah of Mullah Shah, Khawaja Bihari and Jahangir’s tomb.

He further states, "it does not suit kings to demolish old buildings because these are yadgar of our past emperors."

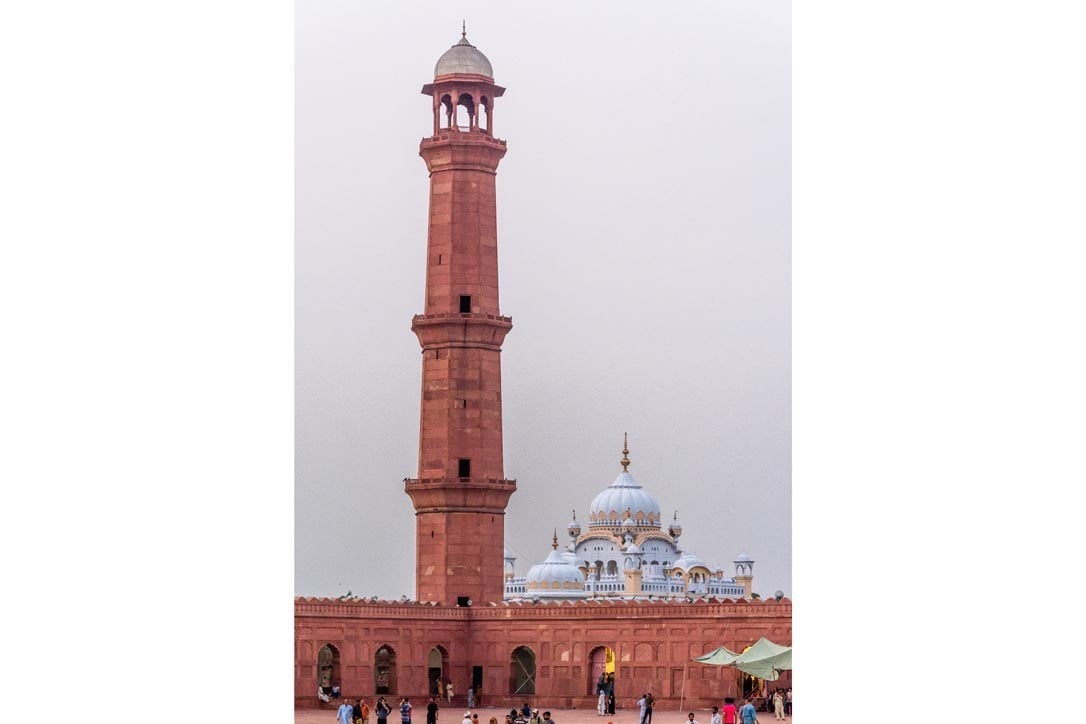

When ‘we’ set our eyes on these ravaged buildings, we are overawed by their grandeur, planning and the hard work gone into it. These shrines and tombs must be worth seeing when first built. But Sikhs erased the signs of ‘our’ glorious rulers. Chishti was all praise for the British because they not only restored those buildings but handed them back to the Muslims. Badshahi Mosque can be cited as an example, which was first a stable and then an ammunition depot under the Sikhs. After the annexation of Punjab by the British, the control of the Badshahi Mosque was given to the Muslims of Lahore -- Barkat Ali Khan was entrusted with the task of managing the Badshahi Mosque.

All said and done, the notion of yadgar as employed by Nur Ahmed Chishti conveys the same meaning as nostalgia. Obviously, yadgar was not at any point of time considered as symptom of a disease, the way ‘nostalgia’ was looked at.

Another point worth pondering is the projection of yadgar as a symbol of Muslim civilisation in South Asia. During the Sikh rule in Punjab, the monuments that represented Muslim civilisational glory were ravaged and plundered, which epitomised decay in 18th and early 19th century. Thus the Muslim discourse shunned these symbols which existed only in the form of yadgar.

Importantly enough, these (architectural) symbols represented the syncretic ethos, which were embedded in the civilisational Islam of South Asia. Once it was seen in such a dilapidated state, Muslims flipped the central postulate of their ‘being’ from the ‘monument’ which was historical and represented their civilisation and culture to the ‘text’ and ‘scripture’. Therefore dargah (shrine) was replaced with the mosque and sufi substituted with maulvi.

That indeed proved ominous for the Muslim civilisation in South Asia.