What is wrong with the local government system in Punjab?

It took Punjab more than a year to complete the electoral process to put in place the much-awaited local governments. This happened after years of dilly-dallying on enactment of the law to introduce this layer of governance and undeniably, it was the insistent pressure from higher judiciary that made it possible.

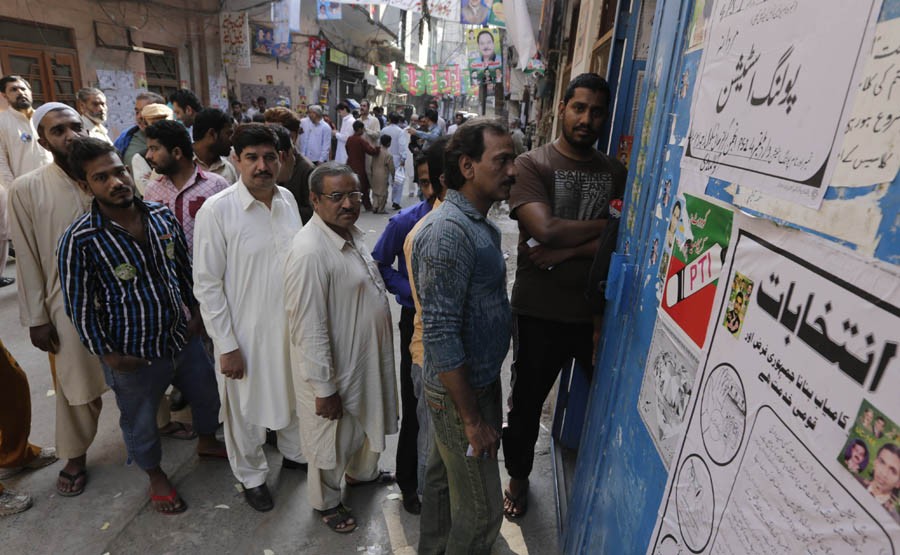

The first stage of polling started in October 2015 and was completed in March the following year. Elections on reserved seats took a few more months and, finally, the chairmen and mayors were elected towards the end of last year. The Mayor of Lahore took oath just days ago while the rest from the province are yet to be initiated. Only after that the process of ‘transfer of power’ will start.

A good reading of the law makes it evident that the new system is all about maintaining the old style of government. It has stark similarities with the Government of India Act enacted by the colonial rulers in 1919. They had wanted to give the ruthless rule of gora sahibs of Indian Civil Services a democratic façade, nothing more nothing less.

The introduced system of diarchy between the appointed bureaucrats and elected representatives was heavily tilted in favour of the former. The power flowed from the crown through bureaucratic channels and ‘the people’s representatives’ were awarded the first right to enjoy a dip into it, albeit with a notice that ‘terms and conditions apply’.

The Punjab Local Government Act 2013 has basically rephrased the same ideas in present day lingo. The hesitant democrats, presently ruling the country, have been overly wary and cautious; it took them way too long in taking even small steps towards implementation of their own law.

Read also: Money to the grassroots

Nobody has an idea when this system will be fully mobilised and the common voters will start accruing its purported benefits. Under the law, the provincial government has the authority to dissolve these governments before the general elections that are, incidentally, only a little more than a year away.

Even if these governments are made operational any time sooner and are allowed to continue past the general elections, one can expect little in terms of devolution of power that was supposed to be their prime purpose. As per laws, the bureaucracy will continue to retain all powers, as an agency of the provincial government. The elected representatives’ role is advisory at best.

So has the long drawn, arduous process been a completely futile exercise?

One can be sure that it will have hardly any direct impact on governance and affect no devolution of power. But the process has generated some interesting politics and is likely to have an impact in the long run.

To start with, there have been no surprises in these elections, neither at the provincial nor district, village or neighbourhood level. Barring a few exceptions, it was a cakewalk for the party in power in a province. PML-N in Punjab, PPP in Sindh sans Karachi, PTI in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and even MQM in Karachi -- all were able to mirror their successes at the local levels.

With all the powers effectively lying with bureaucracy, controlled directly by the provincial government, no one had the incentive to defy the existing power equations. It was about claiming a share in the system by supporting the status quo and not about gaining power by disrupting or challenging it.

The ruling families in provinces maintain a coterie of loyalists who are the prime beneficiaries of their patron. Then each of these loyalists has their own bands of devotees who in turn boast of small regiments of followers (also known as party workers). The lowest rung maintains active liaison with a bunch of voters each.

This patronage system dispensing power to a pyramid of political actors is well entrenched in the country. Each actor is a client for the tier above and a patron to the tier below. The top tiers draw their legitimacy from the national or the provincial elections while the tiers below them depend on their patrons (the parliamentarians) not only for small favours but also for their position in the power pyramid. If an elected representative stops offering favours to one of its clients, the latter’s position as patron to his/her clients is jeopardised.

The local elections are likely to change that.

All the political actors, down to village and mohalla level, have now been elected through popular vote and thus have become legitimate claimants to power. So what was earlier bestowed upon them as a favour by their patrons, they can now claim the same, or more, as their right.

In short, the local elections have substantially increased the number of legitimate claimants to power at all levels. It is bound to create a lot many frictions and give birth to numerous new struggles which probably would not upset the apple cart, at provincial level, at least in the short term, but would certainly require frequent fine tuning of power equations at all levels. This would offer opportunities to the ruling and the opposition parties, at the national and the provincial levels, to frequently intervene and politick at the local level.

This rather new phenomenon has already made itself visible in elections of chairmen and mayors.

In local elections, the PML-N parliamentarians in Chakwal have revolted against the party decision to favour a new powerful entrant to the party who had earlier been opposing the PML-N in the district. The party thinks he is too powerful to be left out for the opposition to harvest while the party’s incumbent MPs feel threatened by his presence and are contemplating their next move.

Some of the elected PTI members in Faisalabad have voted in favour of the PML-N candidate for the position of mayor, in an attempt to find a place within the existing patronage network. This has infuriated the PTI leadership which is acting against its members.

In the recently held by-election in Chichawatni, the PML-N was successful in making its Araeen supporters vote for its Jatt nominee against the powerful PTI candidate. In the context of local biradari rivalries, this was asking for a bit too much. In district council and mayor elections, held weeks later, however, Araeens were paid back as they were given an upper hand by the party in district chairmen and mayor elections.

In another recent by-election in Jhang, the PLM-N nominee was defeated by the candidate of the ‘banned’ Ahle-Sunnat-Wal-Jamat. The group that the PML-N nominee represented, however, has reclaimed some position within party, and its patronage system, by overwhelmingly winning the local elections from the PML-N platform. It could also be seen as the PML-N’s attempt to keep alive its patronage network in the district, bypassing opposition member elected to the provincial assembly from there.

All of the above anecdotes are related to the elections of the top slots in local government system. There certainly has been much more wrangling in elections to the tiers below this level.

This makes it evident that as the local government system sets in, the parties will have to increase the level of their skills to manage their patronage networks. It will require them to go beyond having a few firefighters or some wheeling and dealing experts among their ranks to handle local intricacies and ‘emergencies’.

Hopefully, this will help them realise that the power has to be devolved to the next tier, if not right down to the voter level, in an institutionalised manner under some acceptable principles.

This seems to be the only palpable political outcome of this grand exercise.