The dearth of consistent and reliable data on key economic, social and demographic indicators is responsible for faulty policymaking

Both national and international statistics point to serious shortfalls in current socio-economic indicators of Pakistan. Categorised as a lower middle income country, Pakistan ranks 147th (out of 188 countries) on the Human Development Index and 30 per cent of its population lives below the national poverty line (World Bank Data 2013). The unemployment rate is 6 per cent, literacy rate 58 per cent, and gender inequality persists as female participation rate in the labour market is at a meagre 24.6 per cent.

Frequently cited factors that influence the social and economic landscape of the country include poor governance, inadequate budgetary allocations, lack of committed political will and ineffective deployment of resources. All of these approaches to reform project a clear lack of convergence on national targets.

Mobilisation of resources and good governance may seek out a substantial solution to the problem of floundering social indicators. However, it is also clear that the dearth of consistent and reliable data on key economic, social and demographic indicators is partly responsible for the vacuum created by faulty policymaking.

On a scale of 0 to 100, the overall level of statistical capacity of Pakistan, a figure that represents the ability of the nation to collect, analyse and disseminate high-quality data about its population and economy, stands at 75.5, lower than that of both Sri Lanka and India.

While clear, consistent and useable data in not always readily available, the value of an evidence-based approach to public policy cannot be undermined. Access to consistent data, which is comparable across regions and over time, empowers policymakers to steer resources in the direction where change is most desirable, and to improve policy-relevant outcomes.

A strong data infrastructure is therefore an economic imperative, and its presence allows stakeholders to rightly measure the success of development programmes and identify gaps in existing policy regimes. For instance, data on assessment of student learning outcomes and achievement levels lay the basis for reasoned policy analysis of teacher performance and curriculum design.

The current status of data collection and dissemination in Pakistan is far from satisfactory, and free public access to official data is still a distant dream. Timely release of data is perhaps the most pressing concern as data from official sources appear at least 12 months after collection.

The latest version of the Pakistan Demographic Survey is from 2007, Social Indicators of Pakistan was published last in 2011, while the Household Integrated Economic Survey is available for 2001-2002. These provide data on gender, environment and social indicators of the country, with a view to provide a snapshot of rapidly changing social scenarios.

Although statistics are not expected to change drastically with every passing year, the distance between actual data and implementation of policies only widens as delayed reporting becomes a norm. Sometimes incomplete data is unrepresentative of national education standards, as some ‘national’ surveys fail to report data on AJK, Fata or Gilgit Baltistan.

Irregularities in the way data are collected over the years imply that indicators are less likely to reflect the actual scenario. More specifically, indicators such as enrolment rate are not standardised across data sets from varied sources. The difference in calculation may be subject to debate, leading to unclear policy implications. Sampling methodologies are unclear as raw data is made unavailable for public use and questions arise about the rationale for choosing some areas and not others.

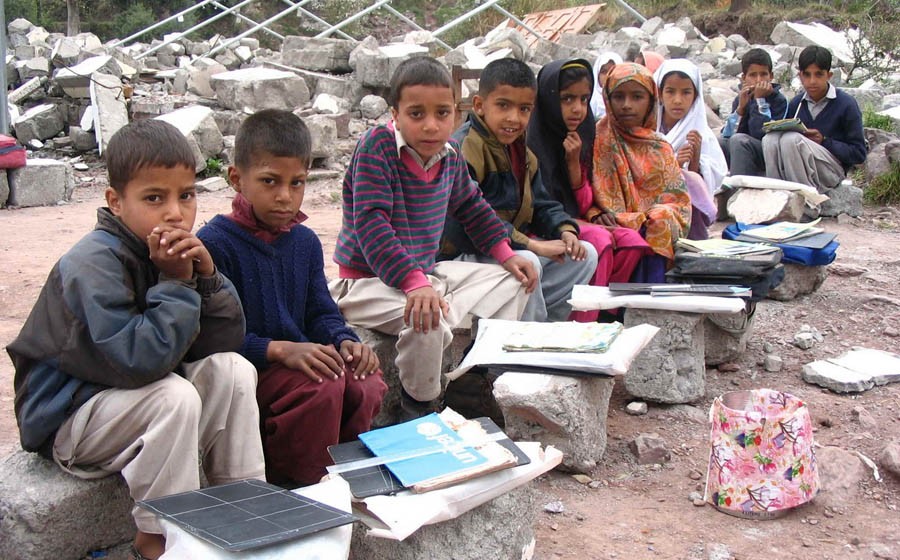

According to the Education for All Global Monitoring Report, the absence of reliable data and statistics for most countries makes it difficult to identify them as having an education emergency even if the state of impoverished educational facilities is evident. There is a glaring learning crisis among children of primary school age in Pakistan, observable by practitioners and researchers alike, and therefore a pressing need for collection of data on teacher education and training in order to work towards favourable education outcomes.

To top this, private school data is unavailable, and researches rely mostly on estimates recorded by national publications. Currently, the same estimates indicate that roughly half the school mix in Pakistan is skewed in favour of private schools. But due to the absence of reliable data on enrolment and teachers for these private schools, it is nearly impossible to direct the right amount of resources towards them. The Pakistan Education Statistics Report rolls out estimates of several indicators for private schools every year, but given that they may be based on an education census conducted some 8 years ago, the caveat in using such data may undermine the whole purpose of evidence-based decision-making.

In cases where non-governmental research organisations are working to bridge the data-gap, the missing culture of evidence-based policymaking stifles the very motive of gathering authentic data and conducting quality research. A USAID Study of Education Research and Policymaking in Pakistan finds little or no coordination between policymakers and researchers in the education arena. Therefore, there needs to be a substantial demand for evidence to construct policies which are grounded in credible data and research.

Another major factor that contributes to a weak national data regime in Pakistan is the non-availability of adequate resources for data-related activities. Staff is often under-resourced leading to inconsistent data reporting trends and weak statistical analyses. Inadequate use of information technology to gather and process data on a regular basis also diminishes the chances of producing a healthy data source for fast-paced policy decisions at government level.

For a consolidated approach to evidence-based policymaking, well-rounded data surveys, which cover all districts and regions in Pakistan, will make up for an acceptable shift. Standard methodologies for collection and computation of data will produce consistent datasets for the purpose of research and policy. Institutional capacity-building and adequate funding sources, however, are necessary ingredients for upscaling data collection techniques.

In addition to this, gaps in complementary data must also be minimised. As with other macroeconomic indicators, it is mandatory to note that access to education is contingent upon social and economic support structures. And so, population census, household surveys, national income accounts, inflation, and national health surveys, need to be published on a regular basis in order to bridge the evidence-policy gap and to allow development initiatives to sail smoothly to their destinations. At the same time, measures should be taken to ensure that evidence is transparent, independent and open to debate, before it is applied to policy.