What influenced Jinnah’s politics and personality

In a state television programme, organised to commemorate the 140th birth anniversary of Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the anchor quizzed me about the influences that shaped his personality and politics.

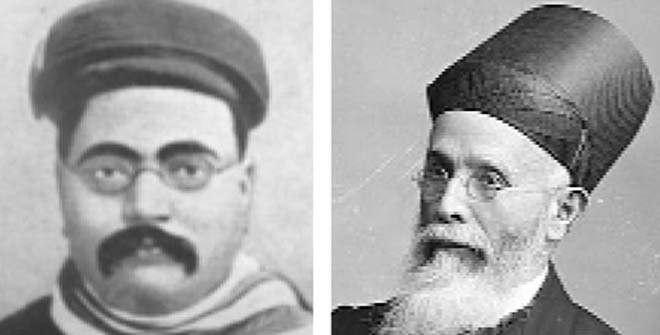

I instantaneously said, Dadabhai Naoroji (September 4, 1825 to June 30, 1917) and Gopal Krishna Gokhale (1866-1915).

The anchor hardly expected the two non-Muslims to have influenced the politics of the founder of a Muslim state, with the constitution proclaiming Islam as the state religion.

Anybody with even a smattering of knowledge of South Asian history is supposed to know these two personalities. But for those oblivious of these persons, Dadabhai Naoroji, known as the Grand Old Man of India, was a Parsi intellectual of Gujrati origin, an educator, a cotton trader, and an early Indian political and social leader. He was a Liberal Party member of parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom House of Commons between 1892 and 1895, and the first Asian to be a British MP.

While in London, Jinnah discovered a passion for nationalist politics, and had assisted Dadabhai Naoroji as his secretary. He returned to India in 1896, not yet 20 years old -- in fact, the youngest Indian to pass the Bar exams and the first Muslim barrister in Bombay’s lawyer fraternity.

It took Jinnah six years to join Indian National Congress. He attended the party’s Calcutta session primarily because Naoroji was President of the Congress.

G.K. Gokhale, a distinguished Chitpavan Brahmin from Bombay, was the other person to influence Jinnah. Gokhale was a senior leader of the Congress and founder of the Servants of India Society. Through the Society as well as the Congress and other legislative bodies, Gokhale campaigned for Indian self-rule and for social reform. He was the leader of the moderate faction of the Congress party that advocated reforms by working with the existing government institutions.

Gokhale became a member of the Congress in 1889, as a protégé of social reformer Mahadev Govind Ranade. Along with other contemporary leaders, like Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Dadabhai Naoroji, Bipin Chandra Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai and Annie Besant, Gokhale fought for decades to obtain greater political representation and power over public affairs for common Indians.

When Gokhale died in February 1915, Jinnah was struck with sorrow and grief, and in May of the same year he proposed the construction of Gokhale’s memorial.

Gokhale had designated Jinnah as ‘the best ambassador of Hindu-Muslim Unity’, therefore, many saw him as his successor. However, around the same time, Mohan Das Karamchand Gandhi came back from South Africa, and made the succession of Gokhale a contested position, which to a great extent determined the future course of Indian politics.

So, both Naoroji and Gokhale influenced Jinnah’s cosmopolitan character and plurality of his vision that need to be emphsised in the present day Pakistan, plagued with social and sectarian fissures and ethic fault lines.

The TV anchor of the programme also referred to the Quaid-i-Azam’s selection of Lincoln’s Inn for doing Bar at Law. But we could not have a detailed talk on the topic. Some writers, including Stanley Wolpert, write in his biography, Jinnah of Pakistan, that he chose Lincoln’s Inn because he saw the name of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) on its entrance. Fatima Jinnah has said the same in her book My Brother (published in 1987 by the Quaid-i-Azam Academy). In the third chapter of the book, entitled A Businessman Becomes a Barrister, she recalls that her brother told her that he chose Lincoln’s Inn over other possible institutions because he read Prophet Muhammad’s name on the "Main Entrance", as one of the great lawgivers of the world.

One may argue that this was the outcome of the particular twist given to history-writing under Ziaul Haq. Renowned anthropologist Akbar S. Ahmed says, "I went to Lincoln’s Inn looking for the name on the gate, but there is no such gate nor any name. There is, however, a gigantic mural covering one entire wall in the main dining Hall of Lincoln’s Inn. Painted on it, are some of the most influential lawgivers of history, like Moses and, indeed, the holy Prophet of Islam, who is shown in a green turban and green robes. A key at the bottom of the painting matches the names to the persons in the picture.

A document available online, titled Mohammad Ali Jinnah: Lincoln’s Inn Factsheet, states that one of the reasons he chose Lincoln’s Inn over any other Inn was that "Watts’ fresco, in the Great Hall, included Prophet Mohammed among the great lawgivers of the world. Other reasons were the large number of volumes in the library and that the Inn was ‘the most economical’."

It seems to me that the last reason given in the factsheet was perhaps one of the most important reasons, if not the single most significant motivation, for Jinnah’s choice of the Lincoln’s Inn.

Several other influences have shaped Jinnah’s personality and disposition; among them were the British legal education and law practice, association with liberal politics in India and inspiration from egalitarianism. These influences also cast a profound shadow on his politics. Given his intellectual and legal background, and identification with liberal political tradition, he could not advocate the Sharia-based polity as some of the commentators go on pleading, ad nauseam.

In the present day Pakistan, what we can learn from him is strict adherence to law and constitution and plurality of the vision that he held and professed.