The consequences for the media have come in the form of increased censorship and heightened intolerance for dissent

We have all heard about the ‘oxygen of publicity’ that terror groups seek -- to project their power to terrorise target audiences. Pakistan has been battling terrorism and violence for the better part of this millennium. But the period 2007-10 was especially vicious when terrorist groups staged audacious attacks designed to become ‘media events’.

These included assaults on key establishments like police academies, military bases, including the GHQ, and universities, that were choreographed to mount resistance lasting several hours. Instead of quick suicide blasts, the principal tactic used earlier, they relied on hostage-taking and spread terror through relentless real-time live coverage on TV screens beaming in homes across the country.

When they realised they were being ‘used’ to facilitate this terror, a group of conscientious senior journalists decided on a basic code of ethics -- to curb direct visual streaming of casualties and to minimise coverage of terror and gore.

The jury is still out on how this has worked out.

Another milestone was the worst terror attack ever in the country’s history -- on school children in Peshawar in late 2014. This resulted in the 20-point National Action Plan (NAP) that listed key areas under which a new counterterrorism policy was enacted.

Point 11 in this list promised a "ban on glorification of terrorists and terrorist organisations through the print and electronic media," thereby officially linking media as an indirect facilitator of terror. But how fair is this linkage and what challenges have accrued as a result of direct and indirect implementation of this NAP Action Point?

The result has been increased censorship, heightened intolerance for dissent and public criticism and, therefore, a compromising of fundamental constitutional guarantees of freedom of expression (Article 19) and right to information (Article 19A) for dubious short-term gains.

Read also: A proscribed prescription

The year 2016 has been a grim year for freedom of expression of both citizens and journalists. Five journalists and a blogger were killed and the high-profile fallout of a news report about civil-military relations published in an English newspaper dramatically escalated the environment of intimidation on the media and increased levels of self-censorship by the media.

Social media was also affected. Adding to the pressure was the passage -- despite consistent hostility to it by the media, the opposition parties, and the civil society -- by the parliament of the Prevention of Electronic Cybercrimes Act (PECA), 2016. This legislation seeks to dramatically restrict the boundaries of criticism aimed at officialdom and allows extraordinary allowance to the authorities to intercept communications by the citizens, including journalists, political activists and rights campaigners.

In recent weeks, civil society activists have come under slanderous attacks online for their advocacy of peace and engagement with neighbours, thereby heightening tensions between supporters of the hard line policies of the security establishment vis-à-vis India and academicians, scholars and progressive commentators.

Author and political and security analyst, Ayesha Siddiqa, came under a vicious attack online by unknown sources, suspected to be close to the security establishment’s views, branding her a traitor and working for the Indian agencies. This opened her to risks of physical violence in an environment of heightened tensions.

The impact of these NAP-inspired developments and measures has been a discernable rise in pressure on the media to censor it through both classic pressure tactics and implied procedural effect. A wide-ranging crackdown on non-state militancy and terrorist violence by the military under NAP, approved by parliament in early 2015 and implementation of which continued deep into 2016, has posed problems in reporting for the media.

While being squeezed by the authorities, including the security establishment and Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authorities (PEMRA), the media and its practitioners have also found themselves being targeted by banned militant and sectarian groups for not reporting about their public acts of violence, reporting on which is now restricted and discouraged under NAP, which warns against ‘glorification of violence’ and reporting ‘hate speech’.

Under this growing restrictive reporting environment, PEMRA has issued dozens of warnings and notices, both general and specific, to news TV channels for criticism of the military, Saudi Arabia, as well as reporting about banned organisations. The irony is that while some of the banned organisations can operate in public space, reporting about events in public space involving these banned groups cannot be freely undertaken.

The squeeze on this reporting angered the banned groups which, in concert with legal religious groups, staged several attacks on media personnel for being out to cover their public protests but ‘not giving adequate on-air coverage’ to their activities, demands and causes.

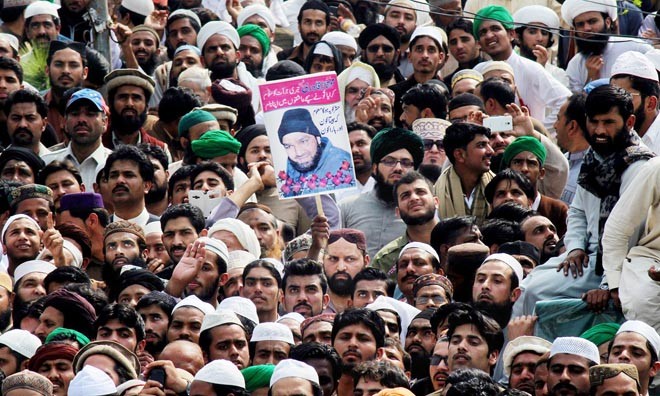

Violence erupted in many parts of Pakistan in March 2016 when thousands of supporters belonging to a specific sect came out on the streets to protest the hanging of Mumtaz Qadri, convicted by the Supreme Court for the murder of Punjab governor Salmaan Taseer for alleged blasphemy in 2011. The authorities had behind the scenes actively dissuaded the media from either live coverage of Qadri’s funeral or reporting about it extensively.

Several journalists covering the funeral were beaten up in Rawalpindi and their equipment smashed. A follow-up remembrance ceremony for Qadri by his supporters on March 28, 2016 swelled into a large crowd which entered Islamabad from Rawalpindi and laid siege to the parliament and federal seat of government in Islamabad for several days. Subdued media coverage of the violent event led to several journalists again being beaten up and harassed, including women reporters.

In short, the media is damned (by the authorities) if it is reporting on implementation of NAP and the tension between the civil and military arms of the government about it and damned (by the militant groups and their supporters) if it does not.

It’s not just the media that has borne the brunt of reporting on issues linked to NAP but also the government. Federal Minister for Information, Pervaiz Rashid, had to be sacked for "failing to prevent adverse reporting on the tensions between the civil and military authorities" about the country’s military-influenced security, counter-terrorism and foreign policies.

A key problem is that there is no framework of analysis resorted to by the policymakers -- to gauge the cost benefit analysis of overtly pressurising the media into wanton censorship and balancing it with the right to know whether policies are delivering.

While mainstream media needs to be more nuanced in its coverage of events that can trigger tragedies, the media cannot be a scapegoat for the deeds of merchants of terrorism. The messenger should not be killed in the interest of muting the message.