Mohammad Ali Talpur’s works at Canvas Gallery Karachi remind of a regular manuscript which does not convey any meaning except an optical impact

In his essay ‘The Spirit of Terrorism’ Jean Baudrillard makes an interesting observation: "…it is the world, the globe itself, which resists globalization."

Like many other cultures that only receive modernity rather than evolving to that stage, our society is also trying to negotiate tradition and modernity. We exist in a world in which influences from outside cannot be avoided. Yet, we are aiming to make a bridge between them besides being aware of the contrast between the two.

This contradiction, which according to the French philosopher is a conflict, has an impact on the art produced in Pakistan. Many artists have invested in cultural/historical forms, in order to create something ‘original’ and ‘authentic’ that represents Pakistani nation.

On the other hand, several painters from the 1950s and ’60s had denied any local link in their art and sought a diction that could be classified international, long before the term was replaced with ‘globalisation’. They moved away from representational imagery and chose the idiom of abstract art. Anwar Jalal Shemza, Ahmed Parvez, S. Safdar, M. Ameen, Kutub Sheikh, Rummana Saeed, Lubna Agha (and from East Bengal) Hamidur Rahman, Aminul Islam, Kibria, Abdul Basit, and Syed Jehangir followed the framework of American Abstract Expressionism, a term that is considered international due to its influence but refers to the hegemony of North American aesthetics.

However, in the later canvases of these painters, one can detect an urge to connect with their place of origin. Thus the most representative outcome from that period of international abstraction is a blend of indigenous elements and the New York School paintings.

The case of Mohammad Ali Talpur is curious because the artist, like the protagonist of Homer’s Odyssey, has travelled to many shores in his artistic pursuits. In a journey, you leave your location, but your location does not abandon you. Similarly, the link with Talpur’s tradition has been an integral component of his art.

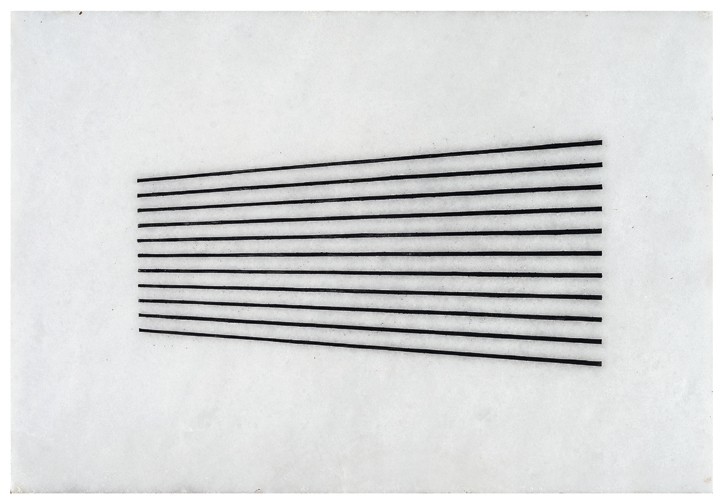

In his recent exhibition ‘Till the Last Look’ at Canvas Gallery Karachi, the artist has displayed works of two types, which may look different in appearance but converge in their essence. In the exhibition, seven large-scale monochromatic works are accompanied with two small works on paper, along with a line drawing engraved in white marble. The difference between the former two is not only of medium but sensibility too; since the paintings in acrylic on canvas are executed in a mechanical manner while smaller inks on paper are based upon gestural marks.

The work of Taplur represents the internal conflict of a modern man in search of his soul (roots?). In his ink on paper, one can trace the tradition of Arabic calligraphy once popular before the arrival of computer. Man’s ultimate goal was to write beautifully because, like an author who picks and discards words in order to make his prose perfect, the scribe was keen on the visual impact of his script.

Taking clue from the fast vanishing practice of writing, Talpur transforms the splendour of calligraphy by introducing the aspect of ‘randomness’ in his works; something that with its broken and expressive letterings reminds of Khate-Shikesta. Here, the artist explores a tradition to create works but does not subscribe to it; these may be interpreted as exercises in Abstract Expressionism.

This tiny bridge between the historic and new may not be a concern for Mohammad Ali Talpur, because he had once gained his training in traditional calligraphy and it endowed him the ability and freedom to extrapolate from the constraints of convention and move beyond.

The works that remind of a regular manuscript are more like the impulsive and spontaneous documentation/denotation of an artist’s moving brush/hand which does not convey any meanings except their optical impact that engages a viewer.

The inherent impulse to locate message or content of an artwork through its visual formulation is challenged by Talpur as he transcends the temptation of ‘reading’ in his paintings. Identification with meaning-- political, religious, cultural etc. -- is insignificant, since these surfaces deal with the magic of seeing. The term ‘seeing’ is so banal that everybody reading these words printed in a newspaper is involved in the act of looking at letters and deciphering them, but Talpur surpasses this familiar activity. For him, the process of viewing is more important than any other reference or linkage.

In his large scale works, a viewer is mesmerised, in fact entangled in the web of lines spread across the surface. The seemingly simple lines offer a variety of visions not expected or foreseen. For instance, the arrangement of vertical lines on two canvases in different patterns illustrates how one element, line, is manipulated to convey an optical sensation that cannot be named but enjoyed. In that sense, the recent work of Talpur is closer to music, which due to its tight abstract compositions has a great effect on the listeners.

The art of Mohammad Ali Talpur, distinct from the usual Op Art baptised as Kinetic Art by Edward Lucie-Smith, addresses a deeper chord in the viewers dazzled by the lines composed either in zigzags, grid, horizontal order, or vertical sequence.

One admits the inadequacy in describing or discussing his new works, because any attempt to trap these into words ends up in reducing the effect of these incredible images. In the presence of these immaculately executed paintings made with minimal black lines, one’s eye starts fluttering and losing all sense of space and sight. Talpur manages all this not through obvious devices but by introducing subtle deviations in ordinary settings that contribute/enhance the pictorial play: a tilted grid, straight lines swelling in the middle of the canvas, imperceptible shift in distance between marks etc. So a viewer’s gaze is glued, binding to his canvas, but blinding as well. After a while everything starts shifting and subsequently disappearing.

Visible, ungraspable and hence incomprehensible, Talpur’s work transports one into a domain where it can be accessed by anyone without invoking their cultural past and tradition. In that sense, his art is merely about visual experience, exposure and interaction with lines, shapes and colours. Paul Cezanne who described his contemporary Claude Monet as "Monet is just an eye; but what an eye" would surely have said the same today: Talpur is just an eye, but what an eye!

The exhibition is on from Dec 13-22, 2016