Deterioration of Pakistani archaeology stems from the so-called ideological basis of the country

Archaeology has been practised in the areas of Pakistan since the British period. It evolved from the nascent state to a fully developed discipline over the first half of the twentieth century. By 1947, it was bequeathed to India and Pakistan and, like other assets, saw scornful division after rigorous and prolix talks. But unlike the former, archaeology degenerated in the latter.

The dismal state of Pakistani archaeology needs to be contextualised against the backdrop of political, academic/institutional, or for that matter social, situation prevailing in the country. Before going into details, let me explicate in what denotation I intend to use the expression ‘Pakistani archaeology’ -- the archaeology done and designed by Pakistani researchers and archaeologists. It is manifestly different from the works of foreign archaeological missions to Pakistan since Independence.

Political factors relating to the deterioration of Pakistani archaeology stem from the so-called ideological basis of the country. Religion-based identities emerged in articulated way in India during the British colonial rule. Cultic ethos and parochial beliefs developed into particularly two main ‘isms’ viz. Islamism and Hinduism which ultimately were manoeuvered in the creation of the two states of Pakistan and India.

Both astutely constructed their respective histories based on certain mutually exclusive philosophies of life. All this bifurcated the shared heritage and history in such a way that what became of interest to Pakistan turned into a historical anomaly for India and vice versa. As a result archaeology suffered to the extent that if on the one hand Babri Mosque was demolished on the other the Buddha’s statues at Bamiyan and Jahanabad (Swat) vanished.

More importantly, if pre-Muslim archaeology came to prefigure in India, it failed to be passionately owned in Pakistan. We are told that the genesis of Pakistan goes back to the arrival of the Arabs in the eighth century with the implication of a sense of disowning our history prior to this anecdote. This politically formulated sense of ‘otherness’ has ultimately amply ruined the discipline of archaeology in Pakistan.

Read also: Carving history

Even scholars like Professor Ahmad Hasan Dani could not succeed to persuade socio-political elites about deep historical basis of Pakistan. And this typical lukewarm attitude on the part of the state elite is greatly responsible for the now characteristic sterility of Pakistani archaeology.

Lack of political interest has led to institutional futility and academic and intellectual lethargy. On institutional level, Pakistani archaeology has not been at par with archaeology in other parts of the world. No innovations and maturity can be claimed in relation to archaeological planning and management as well as scholarship. From this nonchalant situation emanates another problem i.e. contracting archaeology to foreign archaeological missions. One cannot but agree with Nayanjot Lahiri’s, a famous Indian historian, remarks in this respect: "I don’t think I have ideological problems with foreigners working in the Indian subcontinent but the pity of the situation in Pakistan is that the kinds of contracts that are worked out with foreign archaeologists actually don’t leave to any value addition for Pakistani students and scholars themselves. I cannot for example think of any PhD thesis by a Pakistani that has been done on Harappa or for that matter on Mehrgarh where Jean Fracois Jarrige worked. And one can mention many such examples."

This state of affairs has added much value to the overall body of Pakistani archaeology. But, ironically, it has diminished Pakistani scholarship vis-à-vis the subject. Like the federal and provincial archaeology departments’ personnel, the university teachers have also failed to keep themselves abreast with latest trends in archaeological research.

In such a situation Pakistani archaeologists’ complaint that they are not being given due credit by their foreign colleagues makes no sense. That their works are not quoted and recognised in scholarly publications may be seen due to poor quality of research which hardly makes genuine contribution to archaeological and historical scholarship. The scholastic poverty and intellectual failure are owing to our sheer ignorance of theoretical and methodological developments in the field of archaeology across the world.

Archaeology in Pakistan has to make a consistent interaction with foreign archaeologies. No one seems to have known, appreciated and engaged with the ever-new revolutions and transformations taking place since 1960. Professor Dani, who otherwise is called as the legend of Pakistani archaeology, did not do what he should have done. He made archaeology a university subject and tremendously popularised it across the country. But he could not serve the discipline -- due to his other multifarious interests and pursuits -- the way his Indian contemporaries such as S. C. Malik and Professor H. D. Sankalia added intellectual dynamism to it in the Indian context. Professor Sankalia made Deccan College, Pune, as a fertile space for archaeological discourse and historical narratives and experimental considerations and interpretive models. He left behind a galaxy of successors who are known as authorities on South Asian archaeology.

I believe that not more than three or four Pakistani archaeologists have sound understanding in relation to trends in archaeological research. And this negligible number has its involvement in, what I call, epistemological discourses (the processes and debates regarding knowledge production).

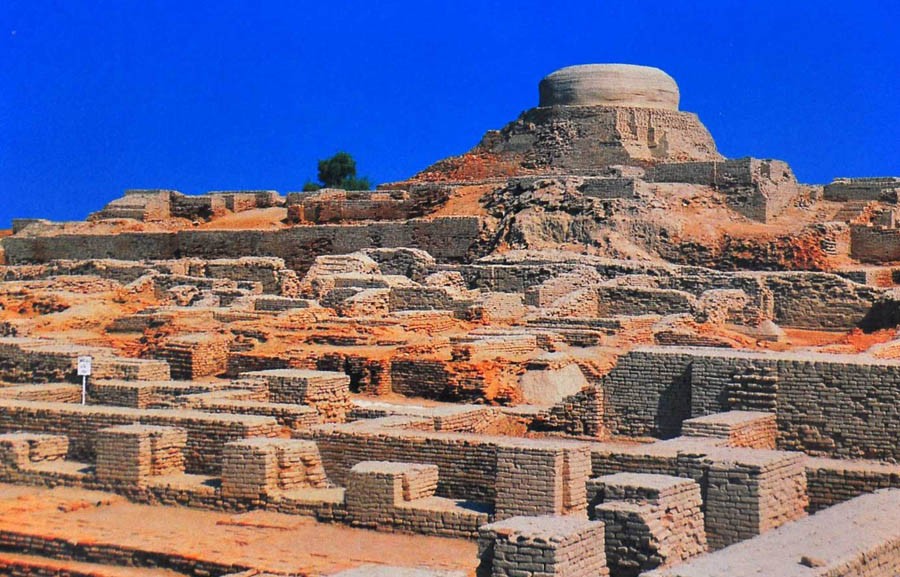

And all this has detrimental bearings on society as a whole. Disowned by the state and throttled by scholars archaeology could not fascinate the people. It is not viewed as a commodity in economic terms and as a resource from moral standpoint. Thus, it presents a view of desolate ‘khandarat’ utterly deficient of any utility. Hence, a speedy disappearance of our scarce and precious cultural heritage.

A pertinent question here is as how to change this situation? It requires serious deliberations and extensive debates to come up with viable solutions. However, for the moment one can make some suggestions.

First and foremost, the state and statesmen should make timely initiatives concerning policy formulations about archaeological heritage and archaeological scholarship. The past should be owned by devising new paradigmatic considerations vis-à-vis moral and cultural priorities.

Second, archaeological management and archaeological research should internalise some moral and intellectual principals, namely sincerity, dedication, innovations, originality, methodological vigour and, above all, a real feeling for history. It will enable us to make our scholarly presence felt in the global community of archaeologists. It will soundly equip us make our own intellectual representations and present indigenous perspectives about our history and culture. So far we have been the passive receivers of historical reconstructions made by outsiders.

Another crucial point can be noted here. Given the fact that we have not been part of the ongoing process of knowledge production activity, we are highly prone to hold theories about history and historical developments which appeared in early twentieth century. Though, they have long been shown as invalid and, thus, discarded. One common place example which comes to mind is the theory of the so-called Aryan invasion of the subcontinent and the disappearance of the Indus valley civilisation at their hands. One can count many such examples.

Lastly, if the state determines and scholars start working with dedication, society at large will be successfully engaged with its historical and cultural heritage. And it is through community involvement that the direly needed preservation and potential public utility of archaeological heritage can be guaranteed. And this prudent strategy of state-society-academia interface shows the way out as far as the present dismal state of archaeology is concerned.