How the lowest tier of governance can become the first tier of democracy?

The lowest tier of governance is, plausibly, considered as the first tier of democracy. Nevertheless, the first tier of democracy in Pakistan has long been misappropriated as an extension of unrepresentative military-led central authority. This has been viewed as a regime strategy, which hegemonises the basic political unit (ward) by creating a new electoral college in search of legitimisation. Three similar interventions -- first the Basic Democracies 1959; second, the Local Bodies 1979; and lately the Devolution Plan 2000 introduced by Ayub, Zia and Musharraf, respectively -- indicate the intent of strategic framework of local governments under military administrations.

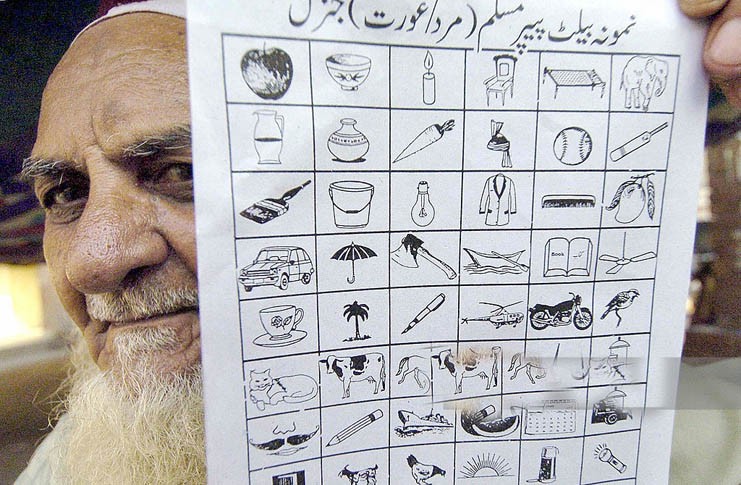

How the strategic framework of devolution is evolving in post-2008 democratic transition is a case for some new insights, opportunities, risks and reversals. For example, this is the first time in the history of Pakistan that a universal democratic coverage has been achieved through party-based elections at three tiers of governance including cantonment boards. However, Fata remains excluded. (Gilgit-Baltistan and AJK are still run under ‘informal federalism’ therefore not included in this example).

The new political framework breaks away from the prototype model of local government and provides space for introducing varying forms in respective provinces, including Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT). Being an exclusively provincial subject, the contours of local governments are being determined by the contextuality of power and political will of ruling parties in each province. The role of civil society actors in this federalised political environment also needs to be redefined as most of the power, resources and authority have been shifted to the provincial capitals through the 18th Constitutional Amendment and the 7th NFC Award. Therefore, engagement for substantive decentralisation has to be realigned with provincial executive and legislature.

It may be intriguing to note that all political parties contesting general elections 2013 are in power and simultaneously in opposition as well. The PML-N is in power in Punjab and Balochistan whereas it is in the opposition in KPK. The PTI is in power in KPK and in the opposition in Punjab. The PPP is in power in Sindh and in the opposition at federal level. The MQM has been sharing power until recently when Ishratul Ibad left the Sindh Governor’s House last week. The JUI remains everywhere as a constant shareholder in the government.

The political power dispersed across diverse political actors in the current milieu will determine the next level of contestation for control over resources and discretion over development priorities. This ensuing contest will be negotiated between local governments and provincial governments.

The ongoing provincial-local government contestation is likely to transform into an intra-party contestation as the newly elected local government representatives would be vying for more resources and authorities at the local level so that they can respond to the needs of local level electorate. Whereas, provincial executives would fear losing grip on resources if ‘diverted’ at the local levels through local representatives. They understandably fear that with this diversion of resources they become less effective if not irrelevant in terms of local level service deliveries -- which is a key instrument of patronage-based politics at the local level.

However, this contestation within provincial ruling parties can trigger and facilitate a process of redistribution of power, resources and authorities between provincial and local governments.

Experience suggests while decentralisation of functions and resources to local levels is necessary, it is not sufficient to improve local democracy. Political economist Ali Cheema has argued that in certain situations, decentralisation allows local elite to capture decision-making structures and reinforce their power and influence. In the same vein, Dr Akmal Hussain pointed out that earmarking development funds from the budget to the politicians under the Basic Democracies, the People’s Works Programmes, Khushhal Pakistan programme and other schemes designed by the federal level governments paved the way for the enrichment of the elected officials.

How to address the risk of ‘elite capture’ under decentralisation is a critical question for all political parties to respond to. The ongoing patterns of increased political and oppositional accountability, growing digital empowerment and dynamic civil society specifically within the context of the Right to Information Law, have the potential to counter elite capture under evolving decentralisation in the country.

A number of studies show that three experiences of local governments under military regimes contributed to depoliticisation and polarisation of society by solidifying biradri, sectarian and other expedient networks by reducing electoral choices through non-party elections. Some analysts have termed the formation of local government under military rulers a form of a ‘decentralised despotism’ in Pakistan. On the other hand, democracy is not completely insular to similar traits of power politics, but provides a relatively better accountability mechanism for citizens, electorates and civil society.

Though, the despotic structures of patronage introduced by military-led local government still exist and remain operative in everyday political transactions underpinning the real politik, the introduction of party-based elections at the local levels opens the possibility of re-politicisation of society. This is likely to compel political parties to engage proactively with their cadres at the grassroots’ level.

It is anticipated that if allowed to evolve, the ongoing process of decentralisation will enable the lower tier cadres to negotiate and demand more investments at the lowest tier of governance and reclaim the proverbial ‘nursery’ of democratic politics -- and thereby turn the lowest tier of governance into a first tier of democracy.