A Pakistani singer receiving an award from the Afghan government proves that art can surpass tensions between states

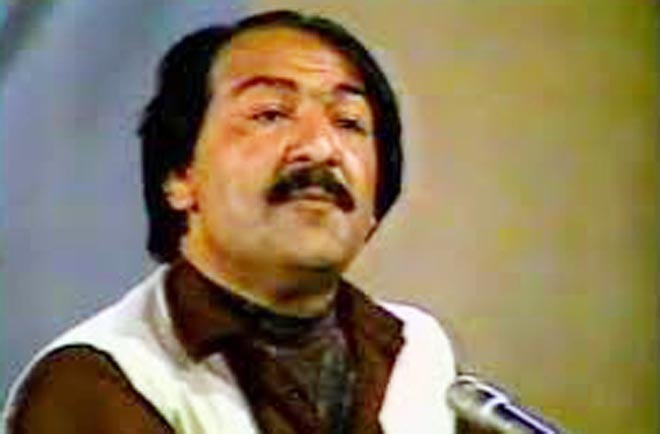

Earlier this month Ustad Khyal Muhammad was bestowed upon with the Mir Bacha Khan Award by the Afghan consul general in Peshawar. Present in the Nishtar Hall on the occasion were Governor Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Iqbal Zafar Jhagra along with many others from the world of art and music.

One had not heard about Khyal Muhammad for years now. There was a time when he was the dominant voice in the music of the Pakhtuns. One read about ten years ago that he had had a stroke and was recovering from it. When he received awards from the government of Khyber Pakhtunkhawa some years back, he was in the news once again. Surprising, because his ghazals and others songs were heard on the cassettes in chai/ qahwah khanas, buses and trucks all the time.

This was the world before the upheavals in Afghanistan -- when a visit to Kabul did not even require a visa. Permits or red permits, as they were called, took you across the Khyber Pass to Jalalabad and Kabul and the cinemas of the city where many Pakistanis just went to watch Indian films. Shopping too was a pastime, and the soulful voice of Khyal Muhammad accompanied you on the journey.

But then he disappeared like the Kabul of that era and it was a pleasant delight to read in the press and watch him being awarded what is probably the highest award by the Government of Afghanistan on electronic media. And he came to receive it in a wheelchair, looking frail.

Born in 1946 at Chora village, Khyber Agency and in a family of musicians, Khyal Mohammad launched his singing career at the age of 13. Khyal’s brother, Saif ul Maluk, a popular singer himself was the one who introduced him to Radio Peshawar where he first performed in 1958. For the next decade, he put all his energies on playing instruments such as the tabla and harmonium, finally switching to singing and recording ghazals in the late 1960s. This decision to go against the tide was received well and his songs became popular in KP. Later on, in 1973-74 Khyal Mohammad even appeared in a movie, Dara-i-Khyber.

He often toured Afghanistan, Europe, the UAE and the USA. He received the National Film Award for playback singing in 1991 and the President’s Medal for the Pride of Performance, two National Awards and a gold medal from PTV which was presented by Noor Jehan. In April 2009, Chief Minister Ameer Haider Khan Hoti also gave him a monetary award on behalf of the provincial government for his services to Pashto songs and ghazals.

He chose to sing the Persian/Dari/Pashto ghazal in a society that was too hooked on singing folk numbers and other forms of popular music. It is a little difficult to tell whether singing ghazal was a principal vocation with vocalists because Afghan music has been neglected between two huge musical systems -- Indian and Persian. Quashed between these two, Pashto musical expression has thrived but is not given due consideration by musicologists and historians of culture.

For the past one hundred and fifty years, the court in Kabul had been deeply influenced by Indian music and many musicians were given incentives by the court to settle in Kabul. It came to an end with the Soviet invasion in 1979 and the fall of Zahir Shah.

It appears that this time round the artiste and the art have proved to be bigger than the tension and estrangement that exists between the two states. The award bestowed upon Khyal Muhammad -- despite the differences between them -- has brought the two countries together, even if it were to recognise great vocalists of a culture that straddles both sides of the Durand Line. But the pertinent question to ask is whether the art and artistes are big enough to offset the tensions that exist between states. For it can also work in the opposite direction as with India and Pakistan. Here the tensions outweigh the commonality of the arts and artistes, create further stresses rather than bringing the two societies together. Dilip Kumar’s award by the Government of Pakistan did create lot of unease in India and the toughening of stance of many Indians towards their leading film star.

It also happens that one country recognising and rewarding artistes of so-called enemy countries is seen as a back-handed compliment. Recognising that the artiste is read by the home country as a comment on not appreciating and responding to the needs and merit of its own populace and thus is perceived as picking holes. Rather than bringing the two together it can initiate a tit-for-tat response that works negatively in the affairs of foreign relations.

As it often happens in the India-Pakistan quandary, it is more about point scoring than sincerity about the two countries sharing something. Yet, share they do, as Indian films are seen in Pakistan on a wholesale level, and much of Pakistani music, art heard /seen and appreciated in India but it is not strong enough to bridge the divide as it all falls asunder on national nomenclatures the moment the tensions heighten. Artistes become the objects of fear and resentment and are targeted for being unpatriotic when being unpatriotic is farthest from their minds. This creates division among the artistes themselves; those who are left behind accuse them to the extent of labelling their artistic pursuits as acts of treason. But one wishes it were not so, and the art stays and plays its principal role -- in bringing people and societies together.