A gifted producer, Yawar Hayat, was the first to infuse brilliance and experimentation into television plays

There was a time when television was considered a lesser medium; obviously, the comparison was drawn with film. It was said that television only produced personalities, film produced stars while theatre produced actors. But, in the case of Pakistan, it was never really true. Television, despite all the limitations of the medium and tight state control, said something to the people which films repeatedly failed to do.

Teleplays emerging from under the draconian social and political censorship managed to talk relevance in a society that was scared of facing the truth and recoiled ungracefully in face of vengeance, violence and censorship. The people who learnt the difficult craft of walking this tight rope comprised the first batches of television producers, skilfully negotiating the space between the rock and the hard place to still appear relevant. One of the brightest of that lot was Yawar Hayat.

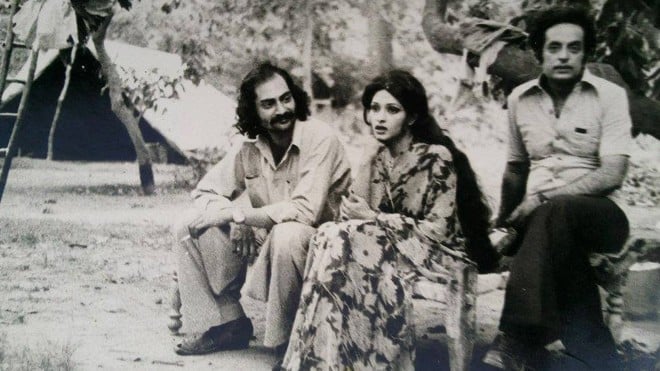

Strikingly handsome, he was something of a maverick artist who lived only in the world of dreams. But that afforded solid foundation to his creativity. One of the first to infuse brilliance into television plays, he could delve deeper into the scripts and characters to engage purposefully with the human condition as it existed in the second half of the twentieth century in a society like Pakistan.

Pakistan Television Lahore was a tiny studio in the premises of Radio Pakistan. In its office across the road, in a crumbling colonial era bungalow, all the producers sat in two large rooms. The roof was rickety and mud kept dropping at regular intervals from the ceiling. The walls of the rooms were partially covered with chiks to conceal the peeling of the plaster and whitewash on the walls. Small tables were individual offices of these producers and from those tables one could tell whether Mohammad Nisar Hussain or Kunwar Aftab would be found at this point in this building. Many artistes, actors, singers, musicians and writers were found in those rooms or the lawns outside chatting, gossiping, waiting, pondering or in a state of anxiety that precedes a performance.

Whenever a table was occupied with people huddled around, it was a clear signal that a rehearsal of a play was on. In such huddles, a strikingly handsome figure would be at the centre of it all as one got to know Yawar Hayat.

In the smaller circle of viewership, television initially achieved its highest quality. The producers could cater to a public that held a certain expectation of the programmes and was not as wildly diverse as it became when the outreach of television grew. So when plays were telecast live in the beginning, the standards to follow were known and were achieved. Gradually, these standards started to get fuzzy as there were many interpretations to what a good programme or particularly a play meant. Yawar Hayat achieved his greatest creative boost when playing to small audiences with plays of highest aesthetic quality.

Pakistani cinema was criticised for lacking realism and portraying an image that furthered the-song-and-dance fantasy. Television, in contrast, was its exact opposite where the possibility of fantasy was also minimised by the limitations of the medium. But it was not only the limitation of the medium that remote-controlled the plays but a deliberate policy of fostering realism and providing something to the viewers that cinema did not.

But this mantra of realism also made the teleplay predictable and at times shying away from experimentation. The absence of experimentation is what made the teleplay drag at one level of interpretation; and producers like Yawar Hayat were acutely aware of that. Therefore, they introduced the element of artistic ambiguity in the production of the plays. The ambiguity was not about lack of grip on the craft of production but on the certainty that a certain type of realism did not offer itself to multiple levels of interpretation.

The experiments in the West particularly were seen as an example of this trend, and Yawar Hayat -- within the limitations of the medium -- experimented like no other producer. Especially in those early days of television, Lamp Post was a tremendous production that opened the subject matter and complexities of human condition, not contingent upon the certainty of resolution or having a firm grip on the fluidity of the human situation.

At his best, he was tackling obscure situations and character types than dealing with stock characters and situations on television which was the forte of our cinema. But the first transition to such themes and scale was also initiated by Yawar Hayat in Jhok Siyal. The challenge was to distinguish the stock situation with its characters from becoming the replica of the film stereotype. He was successful at this, though it must be added that others who followed him were not that careful or sensitive and started to produce the poor man’s versions of the film type.

He also lived close to my house in the big sprawling bungalow of Anwar Kamal Pasha. In the outhouses of that house many destitute, aspiring, unsuccessful and shattered artistes lived hoping and dreaming to satiate their creative outbursts. One often saw Maharaj Kathak drying his clothes and Nahid Siddiqui playing a dutiful shagird but Yawar Hayat, rarely seen in the sunlight, was a night bird and relished the nocturnal scape while working on a production in the studios. The big bungalow is gone but for decades the portion where Yawar Hayat lived with his family stayed intact. In fact, it is still there but in a state of advanced decay.