Openness and transparency is the cure to many of society’s ills. But what if a small coterie decides what is good for national security while keeping everyone uninformed

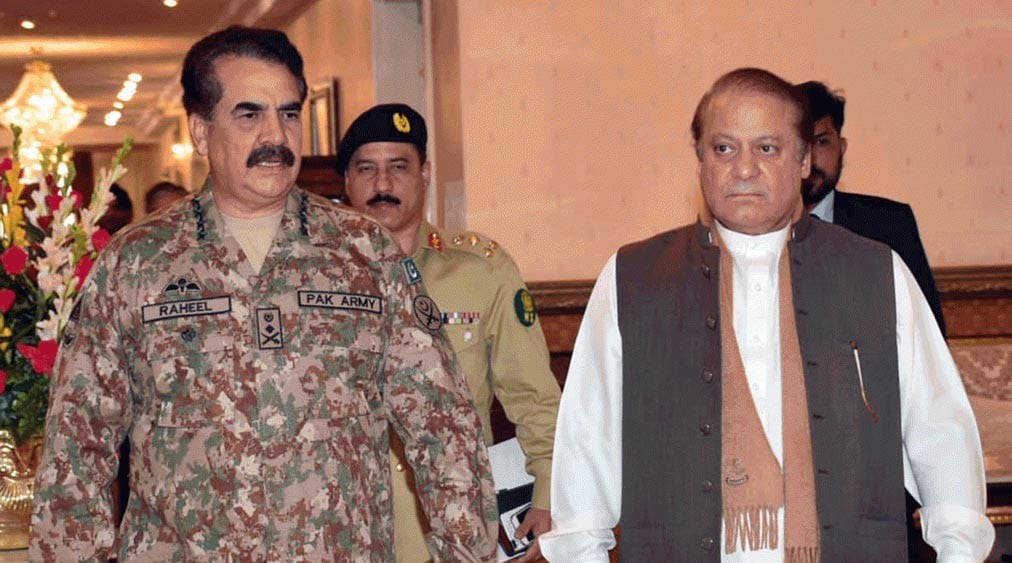

A question that has been incessantly debated since Cyril Almeida’s disclosure of the proceedings of a meeting between members of the elected government and the DG ISI is who is to be believed; the government, which claims it is fighting extremists as hard as it can but is being selectively blocked by the military, or the Army, which claims it is doing everything possible and doing a good job convincing people with its well-coordinated media campaign and slickly produced videos?

Should we place faith in the Army to make the right decisions in the best national interest, even though in the past it has maintained a dual policy as regards terrorists, possibly entitling it to freedom from embarrassing information leaks that could compromise the same national interests?

Or should we put our faith in the hands of elected politicians, like the people of so many other democracies generally do because, after all, politicians always have the Sword of Damocles in the form of the next election perpetually hanging over their heads.

Time and again, we have seen that both are untrustworthy, and are known to take liberties with the truth. As a rule, decisions taken by small homogeneous groups of people behind closed doors tend to be bad. In 1914 Louis Brandeis, a US Supreme Court Justice and advocate of privacy, had this to say on this issue:

"Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman."

Translation: Openness and transparency is the cure to many of society’s ills.

It is not up to any small coterie to decide what is good for national security while keeping everyone uninformed. As a result, we ourselves are still unclear about so many key events in our own country’s history, e.g., key parts of the Hamood-ur-Rehman commission report are still classified. Why was the Kargil misadventure even attempted? How was it possible for Osama bin Laden to hide out right next door to PMA for years? Was Pakistan connected to the 2008 Mumbai attacks or not? Why, after more than a decade, is the Haqqani network still in business? Why can ordinary people be picked up and disappeared for the most insignificant sleights, but Abdul Aziz is free to roam and pick up where he left off after the Lal Masjid siege? We have no clear cut answers because reports are classified and investigation is "discouraged," all in the interest of national security.

Recent news that the government has accepted ISI’s role in checking cyber crimes is just another instance of the government ceding space to the military. Together with the recently enacted and vaguely worded Pakistan Electronic Crime Act, the balance between the public’s right-to-know and national security is definitely tilting towards the latter further reducing space for one to speak relatively freely.

Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index, 2016 has us pegged at 147 out of 180 countries, somehow up 12 places from last year. It describes the press in Pakistan as "targeted by all sides" stating:

"Journalists are targeted by extremist groups, Islamist organisations and Pakistan’s feared intelligence organisations, all of which are on RSF’s list of predators of press freedom. Although at war with each other, they are all always ready to denounce acts of "sacrilege" by the media. Inevitably, self-censorship is widely practiced within news organisations."

An independent and ungagged media is critical to the functioning of democracies. But does our media fit that bill? The short answer, hardly.

Private TV channels have been around for only 15 years, but all those years have not done much for their professional maturity. If most of our daily programmes were in English they would make for a global supply of comedy fodder on YouTube. Most "journalists," with a few notable exceptions, have never seen the inside of a journalism classroom.

Sampling current affairs shows confirms that they are conducted flying by the seat of the pants. Hosts are unprepared, discussions are undirected, questions are elementary and follow-up questions are random. Guests and hosts, annoyingly, crack their insider jokes and speak in riddles on-air, to flaunt how they are in-the-know adding little value for anyone who even skims newspaper headlines semi-regularly.

When terrorism by the TTP in Pakistan was at its peak around 2010-2013, both before and after the Bin Laden raid in Abbottabad, the most informative and factual on-the-ground reporting did not come from local channels, but from CNN, BBC and VICE. Meanwhile, most of our "TV journalists" could not be bothered to leave their studios, and would much rather invite a few "analysts" with questionable to non-existent formal education in the area, usually retired armed forces officer that they were friendly with mostly peddling conspiracy theories.

Pakistani TV journalism’s problems are not limited to issues of style, efficiency and effectiveness but extend to ethics as well, as evidenced by a series of bribery cases. While not all TV journalists fit this bill, the fact is that even after these many years one cannot identify even a handful that are worth our time and trust. Just like journalists, not all media is alike. Print media has been around for much longer in this country and major newspapers have had the time and opportunity to evolve more professional standards of reporting.

In spite of these shortcomings (adapting a quote by the indelible Donald Rumsfeld), you demand transparency and information from the press you have, not the press you might want or wish to have at a later time.

In recent weeks, a surprising number of people have sided with the Army’s / government’s argument that Almeida’s report was detrimental to national security. This opinion is a little hypocritical, especially when we recall how whistleblower disclosures such as the ones by Snowden and document leaks by Assange (including the recent Panama papers) are widely viewed as net positives. Somehow, the recognition that sunlight and transparency disinfects applies only selectively, i.e., only to others.

Even in free societies, freedom of speech is not absolute and has a responsibility clause attached holding people accountable for the direct effects of their speech. There is an argument to be made that in Pakistan the mantle of national security stretches too far and wide already. It is a handy excuse to deny citizens even the most basic information. While there undoubtedly is some information whose publication could endanger lives, much of the time data is deliberately kept out of reach to cloak government departments’ own ineptitude and weaknesses.

When in doubt about choosing between freedom of speech and security, choose freedom of speech. Benjamin Franklin said, "Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety." ~ Nov 11, 1755

It is also important to link people’s inability to demand rightful transparency and accountability from the government back to the failure of our education system. We talk about schooling as teaching children basic numeracy and literacy, indeed fundamental life skills but not the sole purpose of schooling. Schools should also prepare children to become engaged citizens. This requires children to learn the fundamentals of citizenship and democracy, freedom of speech and the role and responsibility of the press to inform the citizenry.

Between 2012 and 2014, HBO aired "The Newsroom" a series written by Aaron Sorkin about TV journalism. It is a story about a fictional news division of a TV channel written mostly around actual world events of the previous year. The show stood out because it considered the numerous facets of the role and responsibility of news providers today from journalists, viewers, commercial perspectives. In an early episode, the protagonist Will McAvoy makes the following statement on the role of media in informing the public. The scene opens with actual footage from 2004 of Richard Clarke, counter-terrorism chief under President George W. Bush apologising to the American public for the administration’s inability to prevent the attacks of September 11.

"Americans liked that moment. … Adults should hold themselves accountable for failure…tonight I’m beginning this newscast by joining Mr. Clarke in apologising to the American people for our failure. …to successfully inform and educate the American electorate. … The reason we failed isn’t a mystery. We took a dive for the ratings. … And now those network newscasts, anchored through history by honest-to-God newsmen with names like Murrow and Reasoner and Huntley and Brinkley and Buckley and Cronkite and Rather and Russert-- Now they have to compete with the likes of me. … From this moment on, we’ll be deciding what goes on our air and how it’s presented to you based on the simple truth that nothing is more important to a democracy than a well-informed electorate. … We’ll be the champion of facts and the mortal enemy of innuendo, speculation, hyperbole, and nonsense. … I’ll make no effort to subdue my personal opinions. I will make every effort to expose you to informed opinions that are different from my own."

That is the level of seriousness, professionalism, ethics we need and deserve from our press.