"Main kaun hoon?" the very first dialogue muttered by the portrait of folk artist Attaula Esa Khelvi, is essentially the crux of the story of From the Bottom of My Art

The ancient Greeks used the one-act play to provide an outlet for the catharsis of their audiences. The modern play is no different. With disillusionment and disappointment being the defining public sentiment of our times, satire has become a popular tool for playwrights in mirroring the confusion of the modern man. The writers of the Urdu play, From the Bottom of My Art, which was staged in Lahore recently, appeared to have had the same idea.

The confusion begins with having chosen an English title for a play that was entirely in Urdu. With the deliberate pun of juxtaposing ‘heart’ with ‘art,’ the title made it clear that the satire here would explore the connection between the artist and his medium of expression.

For a satirical play set to be staged in Lahore, how could Punjabi be left behind, especially in the context of the recent controversy surrounding an elitist private school chain and its ban on speaking Punjabi on campus?

The play begins with a Punjabi-speaking frail old man reminding the audience about the ethics of watching a theatre performance. The director’s intent to set his play apart from the usual productions seen in Lahore continues with the entry of another character from right within the hall. The Baba Jee, aka "Afzal Bhai" is joined by Mehboob, the effeminate curator of an art ‘exhibition’ which provides for the setting of the play. Together, the two interact with the audience, cracking jokes as they select random people and hand them chits of paper before the curtain rises.

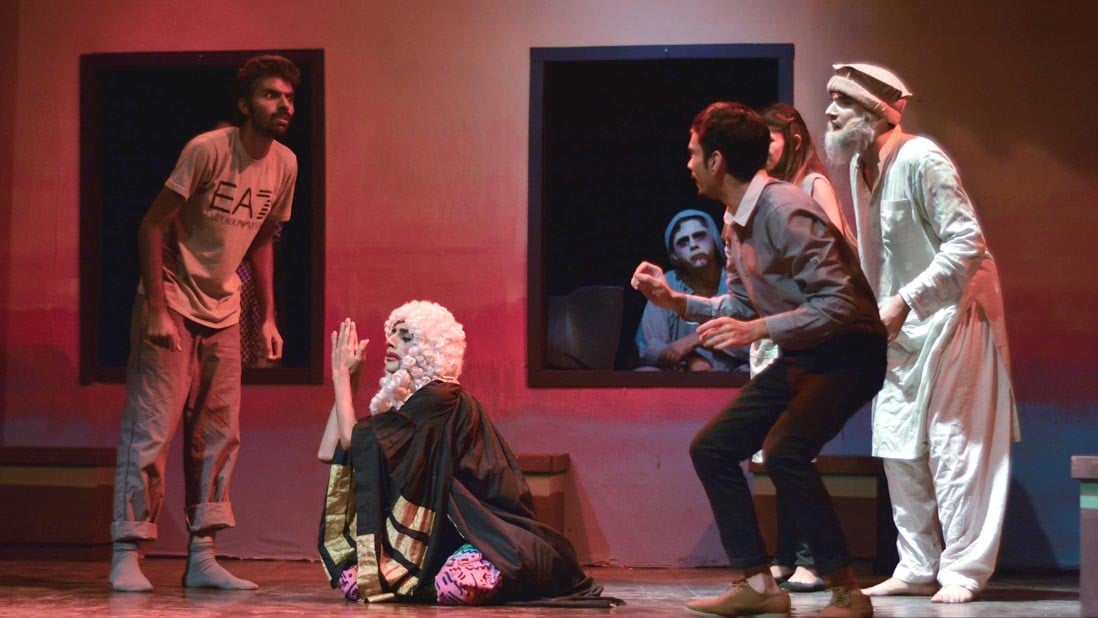

A set, lit by ominous red, orange and blue lights, is revealed. Large frames hung strategically on multiple walls are complemented by the artists’ benches and painting tools. The stage is ready for an unconventional presentation with the ‘paintings’ being real-life people.

"Main kaun hoon?" the first dialogue muttered by the portrait of folk artist Attaula Esa Khelvi, in the truck art painting, is essentially the crux of the story.

From here on, the lineup of male and female painters playing different kinds of artists in our society provides for comic relief and food for thought, by turns.

The scriptwriters made a fair attempt to present the varied styles, motivations, and personalities of artists in Pakistan. There is the art student Najam, played by Syed Murtaza, who is impressed by the foreign vocabulary of impressionism and existentialism. His character is in stark contrast with that of the smart-talking Shehzad.

An unapologetic opportunist, Shehzad, essayed brilliantly by Ali Ahmad Khan, is decidedly the most entertaining character on stage. His gait, gestures, intonation, and facial expressions are on-point, and he easily overshadows the rest of the cast in the character of a swaggering, ‘pseudo-artist’ who says with a smirk: "Controversy creates cash."

On the other hand, the most underwhelmed person on stage has to be the artist called Jannat. Introduced in the pamphlet to be "the heart and soul of the play," Maryam Ahmad’s Jannat is meant to embody the confusion and existential dilemma of a sincere artist who does not want to give in to commercialism like the wannabe artist Mehrunnisa (or Mehru).

Played by Aiman Murtaza, Mehru is the stereotypical art student you’d find at elite institutions, who is simply enamored by the idea of being an artist.

Much as the director and scriptwriter wanted to explore new genres in theatre, their story and characterisation borrowed heavily from the general stereotypes surrounding art and artists in Pakistan. The satire was limited to commentary by the talking paintings whom only Jannat appears to hear.

From offering snide comments on the artists painting them to connecting current news like the rate of suicides in Japan to grave robbers, the live paintings are the unbiased observers in the play.

The play’s attempt to depict man’s confusion in a selfish and materialistic world, through Jannat’s inability to make a truly expressive painting, was an interesting concept. However, the play suffered from its ambition to cover as many social ills as possible. The inclusion of the mime, ‘Joker Justice’, dusted with ‘gunpowder’; the characters’ emotional detachment from the death of their poor studio batman Afzal Bhai; the reference to the recent focus on the lives of the transgender community in Pakistan; and the inclusion of sensationalism hungry news reporters, made for a muddled play that lost its punch somewhere in the many bubbles of scenes being simultaneously enacted on stage.

That said, the acting and direction were commendable, with each actor being completely immersed in their character. With the play being staged across the Alhamra grounds at the same time as the degree show of an art school, the non-ticketed production of DramaEd received a lot of viewers from the art community. From the expressions and comments of the audience, many of them were entertained as well as discomfited by the portrayal of artists. For the cast and crew, that might be mission accomplished.