Machine Learning technology is coming to Pakistan and with it the challenge of layoff and unemployment. What will humans do?

We love quiz shows, and as far as quiz shows go, the American TV show Jeopardy must be among the hardest and most difficult ones we have seen. Jeopardy has been airing on-and-off since 1964 and has produced more than 7,000 episodes to-date. Questions can be from just about any area and require contestants to have an extraordinary level of general knowledge.

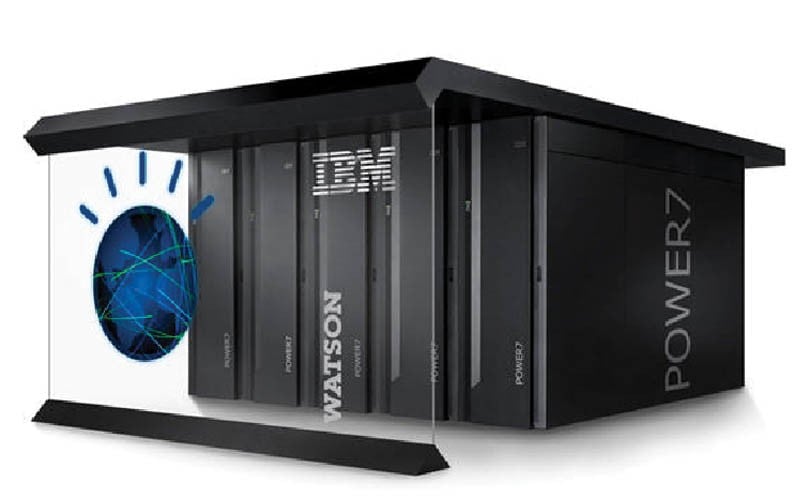

The fact that questions are not phrased in a straightforward manner but are themselves usually in the form of a riddle, makes playing Jeopardy a most human endeavour. But in 2011, Jeopardy’s all-time best contestants were challenged by IBM’s Watson. While special challenges between Jeopardy contestants were nothing unusual, in this one the new entrant, Watson, happened to be a machine. After some initial challenges and subsequent tweaks, Watson beat its human challengers in what amounted to a killing. That historic moment was arguably when the ordinary public was introduced to the power of machine learning.

Machine Learning, or ML, systems like Watson differ from Artificial Intelligence, or AI, systems in the way they are implemented. AI systems are taught how to respond to a set of foreseeable inputs by their builders, their programmers. On the other hand, ML systems devour large amounts of data to learn patterns in it, using a wide variety of techniques (the most recent of which is a technique called deep learning, which has been a buzzword in ML research for the last few years). Even after they are commissioned, ML systems can continue to learn to improve their performance, and learn from their mistakes, much like humans do.

Since then, Watson has been developed for applications beyond answering riddles, and is used as a tool in medical science for cancer research, patient care, veterinary care, clinical trials, travel applications, financial planning, cyber-security analytics, etc. Other application areas onto which ML systems have been encroaching in the last few years include legal applications, loan and credit approval, fraud detection, recommender systems, accounting, surveillance, tax preparation, investment and even a new generation of ATMs, among many others. ML is just one of three technologies which are together catapulting automation forward. The other two are robotics and big data. A widely seen example these days is driverless vehicles, a prime technology that exhibits the use of all three.

Work automation has been happening since the dawn of humanity. But even as late as the 20th century, cognitive tasks were considered beyond the reach of machines and, therefore by extension, "safe" from automation, at least in our lifetimes. However, the ML applications we see being deployed today alone are already projected to displace millions of workers in the coming years.

In the context of Pakistan, where unemployment is high and labour is still incredibly cheap, developing, acquiring and maintaining cutting edge robotic systems to replace manual labour still makes for a challenging business case, unlike in many developed economies. However, the case for automation is becoming less and less difficult to make for a lot of white collar jobs that can be replaced by ML software, where salaries are growing. Reducing the size of the skilled human workforce also takes care of another problem businesses in Pakistan have long been complaining about: the difficulty of finding, training and retaining talent.

ML systems also lend themselves to replacing brick-and-mortar operations by online services. The latter in particular is fuelled by the smartphone revolution spurred on by the introduction of 3G / 4G services and the flood of cheap smartphones.

ML is coming to Pakistan, and unlike Japan, which is at the forefront of automation for decades; it will not come to blue collar manufacturing jobs first. Instead, our local conditions will probably grow from the middle out, i.e., low and mid-level white-collar occupations.

Banks in Pakistan are primed for automation, from fraud detection, to customer service, credit card / loan approval, to tellers. Modern ATM machines, not seen in Pakistan yet, are fully capable of scanning utility bills or printed or hand-written cheque and processing them. Adding this capability alone could probably cut the number of human tellers needed in banks by half.

The insurance industry in Pakistan is still very primitive in the way it does not distinguish between low and high-risk clients when it comes to determining insurance premiums, which may be keeping a lot of low-risk clients away from the insurance market.

The most compelling case could be for certain medical applications. The quality of care a doctor offers is strongly correlated with his / her experience. That experience comes from: A) treating more patients and / or B) remaining up-to-date on current medical research by subscribing to and reading relevant medical journals. However, there is a limit to how much of either a human doctor can do in a lifetime. To jump back, IBM’s Watson is being used in cancer research. Watson has read all published cancer research, and has access to all manner of patient statistics. In a sense, Watson, or a Watson-like ML system can draw on the collective experience of all published medical research, ever, giving it an unmatched level of experience. Theoretically, given a patient’s medical history, that would allow it to recommend the optimal treatment, taking into consideration a multitude of factors, something that is simply not possible for a human counterpart.

Travel agents are already almost extinct in developed countries, because travelers can now find dozens of options for airline tickets for the most complicated of itineraries from their computers within seconds. For most people in the US, tax lawyers and tax consultants have been replaced by software like TurboTax, H&R Block, etc.

The litmus test to check whether a job is at risk of getting automated can be quite simple: Put simply, if you can write down the tasks you perform at your job in a sequence of steps in English language, your job is probably primed for automation, even if the job involves processing images / pictures, handwritten text, video. Even jobs that require conversing with customers are at stake, thanks to advances in digital assistants (think Apple’s Siri, Microsoft’s Cortana and Amazon’s Alexa), and this technology has matured significantly, particularly for English language applications.

New technology trends have always been displacing jobs and entire industries, but the scale of the impact that this technology will have promises to be of a different scale. There are currently 3.5 million truck drivers in the US alone, in addition to bus and cab drivers likely to be replaced by self-driving vehicles. Uber is already piloting its service using self-driving cars in select locations.

If the full potential of ML is realised, and the profit motive of business suggests that it will be, it could spell years of layoffs on an unprecedented scale. If we put on our sci-fi fan hat, this could lead to the most fundamental rearrangement of human society in millennia.

If manufacturers and service providers are able to operate at extremely high efficiency, but a large portion of the population is unemployed / underemployed, who will do the buying and how? Will governments have to provide an unconditional, guaranteed basic income to its citizens to allow them to survive, an idea some countries and municipalities have experimented with in the past few decades?

After years of making news of one breakthrough after the next, a few people outside of academia in Pakistan have woken up to the disruptive potential of ML in conjunction with big data and robotics. But if we were to judge the situation by what we see on people’s LinkedIn profiles, all is well in Pakistan’s tech sector. Data scientists and machine learning experts abound, even though we are intimately aware of the shameful state of mathematics / statistics education that form the foundation of ML and big data, and without which no innovation in this area is conceivable.

The few in Pakistan who are determined enough to develop the necessary technical expertise and are ready, able and willing to take on (local) challenges run into another wall -- the state’s eternal demand for secrecy around any and all data. The government is funded by taxpayers, and the data collected by its various departments ultimately ought to be the government of Pakistan. Whatever sparse data sources there are usually not accessible for use by ML and big data applications.

The situation is little better in the private sector. Businesses are under no obligation to share their data, nor should they be, and don’t. Most notably, the NGO / development sector consisting of thousands of organisations and projects, which exists for the betterment of society and is occupied with the collection of data for much of its time, is no better. The only notable exception is the recently launched Pakistan Data Portal, or PDP (http://data.org.pk), which is hosting some interesting data sets. Like so often the case is, we are at least 10 years late to the party and starting 200 meters behind everyone else.

In a 1969 interview with the Los Angeles Free Press, in response to a question Arthur C. Clarke gave this very Star Trek-esque response: "The goal of the future is full unemployment, so we [humanity] can play. That’s why we have to destroy the present politico-economic system."

We tend to agree.