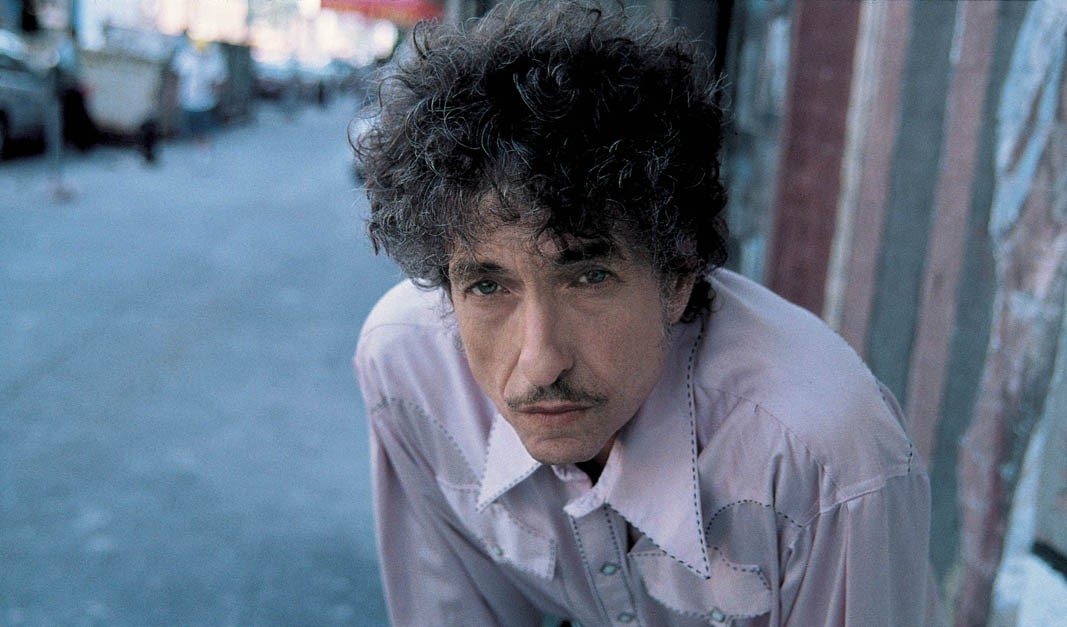

The committee’s decision may have been poor but that doesn’t take away from Dylan’s contribution to the world of American folk and rock ‘n’ roll music

All awards should, and do, court controversies. Awards and their politics are integral to our modern capitalist world. Even if an award originates in an economy that is not purely capitalist, it functions as a reaction to the literary power capitals of the world. That is why criticism, be it political or literary, is important and integral to our relatively new sense of being educated, informed citizens. The Nobel for literature to Bob Dylan too has generated criticism, which is not a bad thing. Even if Ngugi, one of the most cited names, had won, there would have followed a controversy such as why no Pakistani has ever won it. Or why a woman from Africa couldn’t have been chosen.

For now, let’s visit the matter on hand.

About a month ago, I bought a vintage looking record player and checked out a five-disc set of albums from my local public library in San Francisco, including The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, The Kinks, the Woodstock concert, and Dylan’s Biograph. I had never heard Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of ‘Star Spangled Banner’ before and it blew my mind. There are no words in his version. Only his guitar talks. With Dylan I found myself restricted to a handful of favourites. I tried to get my older son, the 12-year-old, to dig Dylan but it didn’t work out. He digs rock and popular music that kids his age enjoy.

Dylan’s place in the history of American music and his influence on future generations in undeniable. Once a musician friend of mine explained to me that one of Dylan’s contribution lay in how he opened up a few chords and bars. And his genius in replacing ‘Lie’ with ‘Lay’, in his song "Lay lady lay, lay across my big brass bed" has been acknowledged. He has been honoured by music related awards and a few years back Obama presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. I don’t recall anyone crying foul. His awards were well-deserved. Why, then, was there such a strong reaction when he was awarded the Nobel? The debate, it seems, is whether or not his lyrics are literature?

The simple answer: To some they are and to some they aren’t.

It is important to keep in mind that Dylan is fundamentally a musician, and the kind of music he creates requires words and those words, referred to as lyrics, form songs. Lyrics can be complex and meaningless, they can also be simple and meaningless, and yet they can also be simple and complex. Take for example his song ‘Lay lady lay’. For musical requirement, he changed lie to lay because it sounded better, and it does. Now block off the music completely and discover the lyric accidentally and then read lay lady lay and it is meaningless to the ear. It doesn’t take anything away from Dylan’s genius though, because he is not writing poetry. Poets tinker with and twist words all the time. They are our primary wordsmiths and creating new language is their job.

People who have defended the Nobel choice have come up with interesting reasons such as Dylan and rock ‘n’ roll’s contribution and influence on English language. But so has Hollywood. From "I have always depended on the kindness of strangers" to "What we have here is a failure to communicate" to "I could’ve been a contender". Every major film industry has shaped the language of its time. If we are into the business of stretching boundaries, then, how about screenplays? Bergman or Godard or Kiarostami’s screenplays are certainly literature. What would be our reaction if a Turkish auteur was awarded a Nobel for literature? Of course some would justify it, hailing it as a right choice, leaving the other half pulling out their hair.

A few of my friends, defending the Nobel choice, have drawn comparisons with Bhakti poets of medieval India, who wrote in rustic registers in which common folks communicated, drawing the ire of those ensconced in the upper echelons of society. They miss a central point, however. The Bhakti poets, such as Kabir and Waris Shah and Guru Nanak and Bulleh Shah to name a few distanced themselves from court culture and lived with those on the margins. They didn’t care for material gains or awards. To lump Dylan, who has no problem enjoying the fruits of artistic labour and the structures of capitalism, with the wanderers of the past and social outcasts is foolish.

Hundreds of years later singers sing the verses created by the Bhakti poets, free of the constraints of copyright and patent. None of the poets mentioned above would have appeared in a car commercial, to say the least. Dylan’s songs, some of them at least, are great songs in the strict sense of rock ‘n’ roll music. His protest against the way America had turned was quintessential. But he wasn’t alone. There was already a strong body of protest literature, especially by African American writers and musicians. In order to understand the rise of Dylan during the 1960s one must also understand the political music by The Weavers and Woody Guthrie, who couldn’t stand Irving Berlin’s ‘God Bless America’ and thus wrote his classic ‘This land is your land’.

The Nobel choice appears even more foolish if one considers the politics of language. When a writer is awarded the Nobel, her work has either been translated into other languages or would be in near future, thus making the work more accessible. But when a musician is given the award for literature, how do you translate his music into other languages? If you are providing people with no choice but to succumb to the power of English songs, is that not akin to spreading English language imperialism? It has been agreed upon that his lyrics are inseparable from his compositions, unless at the cost of devaluing his music. Cinema has the advantage, on the other hand, of subtitles, which music lacks. And that is why they have Grammys and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

There is also another somewhat troubling aspect that needs to be highlighted. After being a part of the Civil Rights Movement in the US, Dylan broke away from the Left over the question of support for the rights of Palestinians by Black Panthers. The lowest moment for Dylan came when he exonerated Israel’s murderous behaviour after it invaded Lebanon in 1982 and massacred Palestinians. The song he wrote was ‘Neighborhood Bully’ which reflects poorly on his judgment, coinciding with his drifting away from progressive thinking of the 1960s towards discovering Jesus. (He also wrote a song taking cheap shots at labour unions even as working class families struggled.) His fondness for racist figures like Meir Kahane is also highly problematic. The lyrics for ‘Neighbohood Bully’ go against the finest scholarship by Israeli and non-Israeli historians such as Ilan Pappe, Thomas Suarez, and Simha Flappan, just to name a few. These academics exposed that the cleverly constructed myth about aggressive Arabs/Palestinians attacking the helpless Israelis was created to ethnically cleanse Palestine of its original inhabitants; a myth shamefully supported for long by filmmakers, writers, and artists.

As for my personal opinion, the Nobel committee has shown a very poor judgement, but they have been known to do this. This, however, does not take away from Dylan’s contribution to the world of American folk and rock ‘n’ roll music.