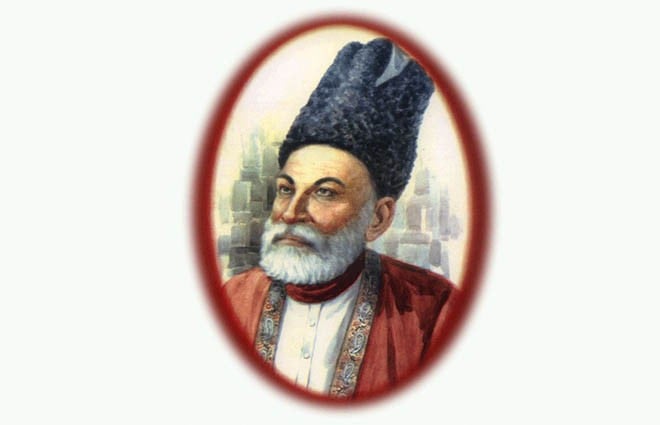

Asadullah Khan Ghalib, like Dr Johnson, was a class by himself. As a man and a poet he offers us his own genius. From all accounts he was a remarkable conversationalist and was vastly gregarious. One of his biographers, the worthy Munshi Malik Ram, has estimated that there were 146 poets tutored by Ghalib in the art of poetry.

The story of Ghalib’s pension is a long and frustrating one which embroiled the poet in a life time of petitions and legal wrangling. The panegyrics he wrote to please the high-ups of the government were of no avail. Eventually, he composed a panegyric in praise of Queen Victoria and had it sent to London through the office of the Governor General. This had some effect. In January 1859 a letter came from London stating that orders would-be issued for Ghalib to receive an honorific title and robes of honour as a reward for his poem. Unfortunately, in May 1857, Delhi was plunged into chaos as a result of the Muslim uprising. Ghalib’s hopes were quashed. He was now destitute.

His forbearance in destitution has to be admired. He could have wallowed in self-pity, but he didn’t. In a letter he rails against the intense heat of the season implying, of course, that the flames were not only in the atmosphere but gripping his soul as well.

"Endowed with winsome virtues..

What is happening these days might

best be left unsaid. In the words of Sa’adi

(the only water to be found was in the orphan’s eye)

Day and night it rains fire and dust, utterly obliterating the sun and stars. Flames shoot up from the earth and cinders shower from the heaven. I wanted to write a full-blown description of the heat here but the voice of reason said, ‘Madman, forbear!. If you scratch your pen against the paper, it will ignite like a kitchen match struck against a stone."

* * * * *

Faced with the prospect of having 20 people (including half a dozen retainers) to feed, and not a penny to earn, a lesser mortal would have lost his equilibrium but not Ghalib. He kept on borrowing money from whatever source was available and ‘supplies’ on credit in the hope that his pension would be restored backdated, but this was not to be. The creditors having lost their patience ganged up on him. Ghalib writes a letter to his friend, Salik, in which he tries to make light of Salik’s losses by making fun of himself.

Read also: Ghalib and his letters

"My very life,

What frightful anxieties have seized you. May God preserve you in good health and make your hopes and fancies realties. As for me I have become a spectator of my own spectacle. In other words I have become an alien self outside my own self.

Anytime grief strikes me I say ‘See? Another kick in the face for Ghalib! Lord, how he put on airs, imagining himself such a great poet, such a learned man in Persian, without an equal far and wide. Come now friend! Face the money-lender! The truth is that when Ghalib died it was the death of a mighty heretic, a mighty infidel. When kings are dead and gone, they are remembered with such titles as ‘Dweller of a Paradise.’ Since he (Ghalib) at least considered himself to be the ‘King of the Realm of Poetry’ to honour him we have conceived for him the titles of ‘The Sire of Fire’ and ‘He who dwells in a Cell of Hell.’ So hail to thee,

Najmud-Duala Bahadur? One creditor grabs him by the throat; another pays him questionable compliment: ‘I say sir, your Eminence, Nawab Sahib! Why do these people insult you? Why don’t you tell them off? Say something!’

What has the shameless wanton one to say for himself? Wine from the local merchant, rose water from the perfumer, fabric from the mercer, mangoes from the fruit-seller and cash from the money-lender; all on credit. He should have given at least a passing thought to pay his bills."

*****

Most of Ghalib’s Urdu correspondence, which has survived, dates from the last decade of his life. There are reasons for this. First, he did not become seriously interested in writing Urdu prose until his later years, having preferred to explore the more prestigious possibilities of Persian in his earlier days. Secondly, most of his letters in Urdu predating 1857 had been lost partly because their importance had not been realised -- and partly because the cataclysm of 1857 saw the destruction of much of his previously published work, both poetry and prose.

Read also: Ghalib & his letters 2

As early as 1858, two of his most favourite pupils, ‘Mirza’ Hargopal Tafta and Munshi Shiv Narain Aram, recognising the great stylistic originality of the letters which they had received from Ghalib, expressed their desire to publish a selection of his letters. While Ghalib was at first cool towards the idea it must have caused him to give serious consideration to the value of the contribution to literature that his letters might make. Besides, Tafta and Aram’s desire to publish a collection of his letters helped assure the preservation of his correspondence, and so he relented. Once word got around that such publication was in the offering Ghalib’s correspondents too, saved every bit of scrap they received from the great man in the hope of having it included in the publication.

*****

Ghalib lived at a time when the Mughal Empire was coming to an end. Her Majesty’s government was about to take over from the East India Company the governance of the huge Subcontinent. He was witness to the devastation of Delhi and its courtly culture culminating in the catastrophe of the uprising in 1857 and its aftermath. The trauma accompanied by his personal losses reflected not so much in his poetry as in his letters

Today, Ghalib’s letters serve as text for the study of their artful use of the Urdu language and their meticulous structure. Written in a manner of conversation which has become a paradigm of Urdu prose, they reflect his joy, his anguish and his profound sense of humour. He rid Urdu prose of its ornate, highly mannered Persianised verbosity and created a stylish simplicity which can only be described as sublime elegance.

As a postscript let me add an extract from one of his last letters:

"Now having reached the last phase of this transitory life. I am a setting sun. If He so wills it, my renown will last till Judgment Day. Hence I pray you to accept these modest offerings, by which I mean these letters written in simple every day Urdu as a boon to the absence of something better"

(Concluded)