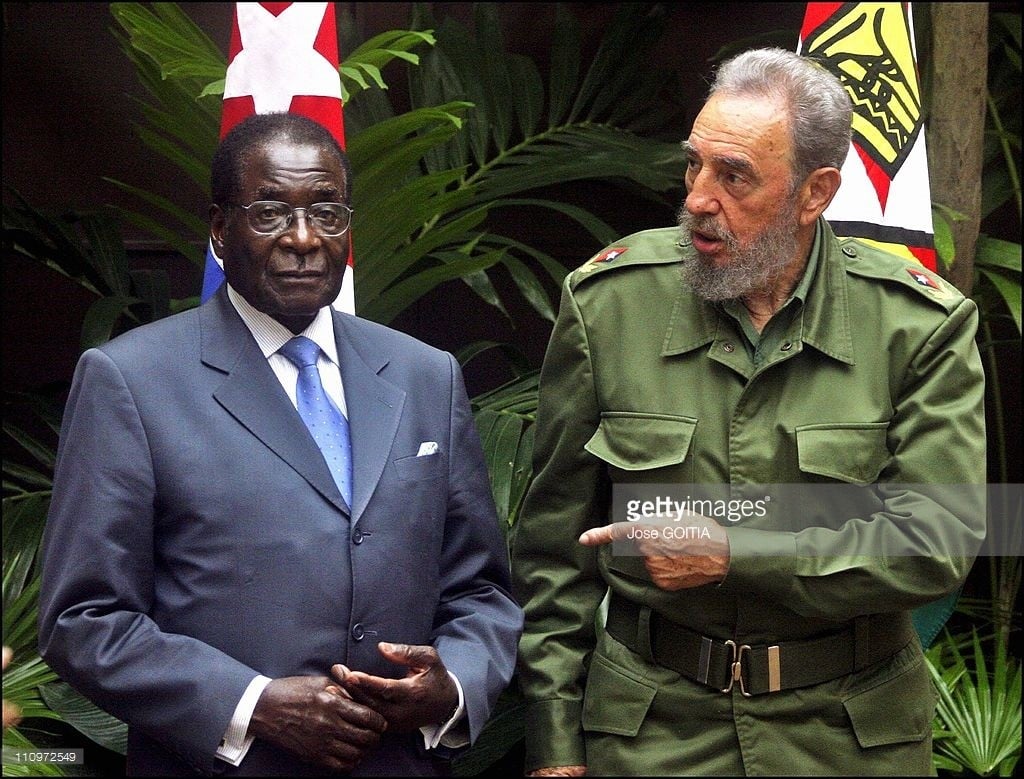

Castro of Cuba and Mugabe of Zimbabwe, both anti-imperialists in their 90s, are still holding to their guns

When Fidel Castro of Cuba celebrated his 90th birth anniversary on August 13, he was looking frail but still ferocious against his enemies of yore. On another continent, Africa, where Castro had sent Cuban troops to fight against imperialist powers, Robert Mugabe had turned 92 in February this year. Both have inspired at least two generations of revolutionaries in the second half of the 20th century.

The two fighters may be fading but their insistence on an anti-imperialist rhetoric is still exemplary. Though Castro is two years younger than Mugabe, he came to the world stage much earlier, while still in his 20s.

The politics of Latin America in the 1950s was forever changed by Castro, whereas Mugabe was still pursuing his education in various African countries. Castro had adopted the leftist politics while studying law at the University of Havana in the late 1940s. By the early 50s, he had already participated in rebellions against right-wing governments in the Dominican Republic and Colombia. His readings of Marxist-Leninist literature transformed him into a formidable speaker who could analyse and present political situation in Cuba and surrounding countries in an easy-to-understand manner to the masses.

A diehard opponent of American influence in his country, Castro railed against Batista who had seized power in a military coup in March 1952 promising a ‘disciplined democracy’. This term became a favourite concept for rulers such as Sukarno and Ayub Khan who used the qualifier ‘disciplined’ or ‘guided’ for their own autocratic ‘democracy’. Castro was against such democracy, but ended up establishing a one-party rule that is still strong after almost six decades in Cuba. From the first failed attempt to gain power in July 1953 to the final triumph of a popular revolution in January 1959, Castro never called himself a communist.

In those five years or so, his brother Raul Castro and friend from Argentina, Che Guevara, were very close to Fidel. Especially, Che played an important role in the transformation of Castro brothers from relatively moderate revolutionaries to staunch communists. The guerilla war led by the trio against Batista’s forces is beautifully reenacted in the film Che: Part One (2008) directed by Steven Soderberg; part two of this film deals mostly with the last years of Che fighting for revolution in Bolivia.

After Batista’s overthrow in 1959, Fidel Castro assumed military and political power as Cuba’s prime minister. Castro’s friendly relations with the Soviet Union alarmed the United States, resulting in unsuccessful attempts by the US to remove Castro by assassination or economic blockade. The counter-revolution activities, including the Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961, prompted Castro to form an alliance with the Soviets who placed nuclear weapons on the island. The ensuing Cuban Missile Crisis is memorable in history as the single most important event of the Cold War when the USA and the USSR brought the world into a sniffing distance with a nuclear holocaust.

While all this was happening, Robert Mugabe of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) was still a relatively unknown figure in world politics. He was almost 40, but still had only a lectureship in Ghana to his credit. Mugabe’s early political influence was the Ghanaian freedom fighter, then prime minister and president, Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972) who had led the British colony of Gold Coast to independence from Great Britain in 1957 as renamed country of Ghana. Others who inspired him included Tanzanian and Zambian freedom fighters, such as Julius Nyerere (1922-1999) and Kenneth Kaunda (b.1924)

At that time, more popular than Mugabe, another leader in Rhodesia, Joshua Nkomo (1917-1999), led the trade union movement and the Rhodesian chapter of the African National Congress (ANC). He had established a National Democratic Party in 1960 which was banned and transformed into Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU). In early 1960s, Mugabe accepted Nkomo’s leadership and joined ZAPU, only to leave it in 1964 to join breakaway Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). One reason for this split was the chasm in the world socialist movement in the shape of Sino-Soviet rivalry to lead anti-imperialist movements around the world.

This schism caused irreparable loss to the anti-imperialist cause, resulting in bifurcation of most communist and socialist parties and anti-colonial liberation movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. In Rhodesia, Joshua Nkomo’s ZAPU remained pro-Soviet, whereas its splinter group ZANU styled itself on Maoist lines preferred by Mugabe. Similar divisions were seen in the independence movement in Angola between the MPLA and UNITA. Angola is important for our discussion because it was pro-Soviet Fidel Castro who ultimately sent Cuban troops to Angola to support MPLA -- a political party that is still ruling since Angolan independence in 1975.

Another point to keep in mind is that Nkomo and Mugabe hailed from two different tribes i.e. Ndebele and Shona. Mugabe’s Shona tribe represents 80 per cent of the population whereas Nkomo’s Ndebele is hardly ten per cent of the total population. This factor played an important role in the ultimate success of Mugabe’s ZANU in the freedom struggle. Both Nkomo and Mugabe spent over a decade in prison under the white minority government of Rhodesia. When finally independence was granted in 1980, as one of the leaders of the rebel groups in opposition to white minority rule, Mugabe was elected prime minister.

Joshua Nkomo was inducted as minister of home affairs rather than his preferred portfolio of minister of defence. He left after two years to launch an opposition movement but after massacres of his Ndebele tribal people -- who were supporting him -- he relented in 1987 to join Mugabe as his vice president. In 1987, Mugabe became the country’s first executive head of state after the controversial merger of the two groups forming ZANU-PF that has retained a one-party rule led by Mugabe since 1987.

Both Castro and Mugabe introduced central economic planning accompanied by state control of the press and the suppression of internal dissent. But similarities end there. Castro was much more successful in establishing a welfare state that provided for basic health, education, water, sanitation, infrastructure, power, and security to people. Of course, not at the level of developed western countries, but much better than many developing countries including Pakistan.

In contrast, Mugabe has led a totalitarian government solely focused on himself and his cronies. He has drawn Zimbabwe into a mire of racism against the white minority and hyperinflation that the Cubans can’t even dream of. While Castro has been sagacious enough to relinquish power to his younger brother, he is still vocal in his enunciation of America from the sidelines. Mugabe is still holding complete power in the face of increasing opposition and rising unemployment.

In the final analysis, Castro and Mugabe both led successful anti-imperialist revolutions in their countries, but Castro has retained his position as a well-respected senior statesman; whereas Mugabe has lost all his credibility and erstwhile respect.