On the ties between the IS and local militants in Pakistan

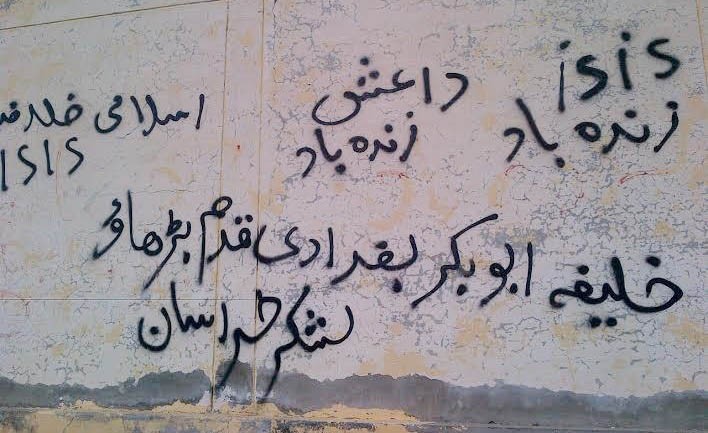

The (literal) writing on the wall first began appearing in 2014 soon after Zarb-e-Azab was launched, roughly the same time when Sunni militants under the umbrella of the Islamic State (IS) established an Islamic caliphate straddling Syria and Iraq. The wall chalkings in Bannu praised IS in Iraq and Syria, lauded the Afghan Taliban and ridiculed the prime minister. The graffiti, in Urdu, was not signed off by IS militants but by Awaami Baghi Group, Bannu Waziristan, a local organisation.

Two years later, the writings have steadily grown and spread to other parts of the country -- pro-IS graffiti can be seen in Karachi, Peshawar, Quetta and numerous cities in Punjab. Some security officials and analysts say that this is all there is to IS in Pakistan, it’s more a "brand name" than a militant force that needs to be dealt with.

After Jamaat-ul-Ahrar (JuA), a splinter group of the Pakistani Taliban (TTP) claimed responsibility for the suicide bombing in Quetta that killed 74 people, over half of whom were lawyers, IS also staked a claim to the deadly attack creating much confusion. In an attempt to untangle the mess, JuA, which had briefly pledged allegiance to the IS in 2014, announced in an audio statement that they should not be linked to transnational Islamist networks such as the IS (which they referred to as Daesh). JuA said their fight was only against the Pakistani state.

After clarifying that JuA -- which also claimed responsibility for the Gulshan-e-Iqbal Park blast on Easter Sunday earlier this year -- has no organisational ties to IS, Omar Khalid Khorasani, their leader added: "Those in Daesh or al Qaeda or any other mujahideen movement are our Muslim brothers."

This shows that while the objectives of local militant groups such as JuA and IS may be different, their ideological motivations are very similar.

"All of these groups: Islamic State, al-Qaeda, Taliban factions, the sectarian groups, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and Lashkar-e-Taiba are cut from the same cloth," said Michael Kugelman, South Asia analyst for the Woodrow Wilson Center, a US-based think tank. This similarity in their ideology creates the fear that over the last two years local groups may have colluded with the IS and given it space to grow within the country. As Kugelman explains, "Marriages of convenience are certainly possible between purportedly rival militant organisations."

In a press briefing earlier this year, Punjab Home Minister Rana Sanaullah said that the Punjab police have arrested 42 suspected militants for having links with the IS.

Additionally, according to news reports, in January this year security forces conducted raids in Islamabad and arrested Amir Mansoor, IS’s Emir for Islamabad. Mansoor reportedly provided the authorities with a list of people who had received training in Afghanistan under a Taliban leader who later pledged allegiance to the IS. On Mansoor’s arrest, a Punjab police official, who wishes to remain anonymous, says that such arrests leave "little doubt about IS’s growing presence in Pakistan, as the group is clearly finding the country fertile ground for recruitment."

In theory, the IS should be competing with militant groups that have been around much longer than them, such as the Taliban with all its factions and splinters. But the reality is that despite the fact that the IS doesn’t yet have a strong physical presence in Pakistan, local militant groups are attracted to it because it enjoys a brand appeal.

Another incentive local militant groups have for tying up with the IS is that as the TTP split into more and more factions and the leadership problems increased, especially after Hakeemullah Mehsud’s death in 2014, there were many disaffected militants fed up with their parent organisation and keen to find something better. IS fits the bill. This explains the Taliban offshoots that flirted with or in a few rare cases, such as with Tehreek-e-Khilafat, formally pledged allegiance to the IS.

Conversely speaking, "the IS has an interest in forming ties with local militant groups because it has suffered major setbacks to its so-called caliphate in Syria and Iraq, and it has an incentive to prove that it’s still relevant. Creating terror in Pakistan and Afghanistan is an excellent way to prove their relevance," says Kugelman.

Secondly, Khorasan, which historically refers to the region encompassing Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan, has a special significance for the IS’s ideology. This includes a prophecy of a Muslim army emerging from the same region to conquer all of the Middle East, including Jerusalem.

Speaking in more practical terms, the IS is invested in Khorasan, and particularly Pakistan because "Pakistan is one of the biggest pools for recruitment for jihadi organisations and the IS is set to take advantage of this," says the anonymous Punjab police official. He says that the IS finds it easy to recruit and build ties in Pakistan because the sectarian variety of militancy, which is ripe in Pakistan, already shares their ideology.

A Karachi-based counter-terrorism analyst, who also wishes to remain anonymous, agrees with this concept. He adds: "Wherever there is a presence of sectarian militant groups in Pakistan -- basically across the country -- the IS would have potential and serving recruits, allies and sympathisers."

It is very easy, explains Ayesha Siddiqa, an independent political and defence analyst, for members of local militant groups to slip from their side into the IS’s realm. She maintains that there is no difference between the religious ideology of Pakistan’s Ahle Hadith and the Wahhabism that IS offers. There is one difference that she offers -- the relationship between the IS and the state and the one between TTP factions and the state are disparate, similarly their strategies on how far they want to take the battle with the state is also not on the same page. "The rest of the ideology is similar," says Siddiqa.

Apart from JuA, another militant group that has been famously linked with the IS is Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ). LeJ, much like the IS is a sectarian-focused organisation which targets religious minorities. The Punjabi police official backs this ideological link by talking about how Malik Ishaq, the leader of LeJ, was rumoured to be considering to join the IS in Pakistan.

Barnett Rubin, a former advisor to the US Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, confirms this link by adding that since the IS is harsher with Shias and non-Muslims, "even more than most Sunni militant groups," the ideological appeal is easy to see.

This presents a huge problem. While LeJ has its greatest presence in south Punjab, the militant group also has a national outreach and has staged attacks all across the country. "There is reason to fear that there could be LeJ members around the country who double as IS members, or at least IS-aligned fighters," said Kugelman.

This does not mean that the IS has already achieved its presence across the country, but it does imply that its influence has long tentacles because of the far-flung presences of groups that are ideologically sympathetic to it, such as LeJ.

Sources in the police said that the Government of Pakistan has a zero tolerance policy for the presence of IS in Pakistan. The anoymous Punjab police official told TNS that the "Pakistani state is not ready to allow ISIS in the country but because of a plethora of jihadi organisations active in the country, they can’t do much about it. There are efforts by the government to combat the IS but the militant group is surreptitiously growing its network by targeting urban middle class Islamised youth."

To a large degree, Kugelman agrees with the police source. He explains that while Pakistan has been willing to try to conciliate those TTP factions keen to launch negotiations with the government, the IS is a totally different beast. Since the IS has no interest in negotiating or engaging with the state and since it exists as a virulently anti-state organisation, it can be assumed that the Pakistani state takes an uncompromisingly maximalist position against it.

On the other hand, Siddiqa said that the state may be appearing non active. "They may not want to attract greater attention to the IS or because the threat is limited and found amongst people that are partners of the state and so they don’t want to draw attention." Another explanation offered by the Karachi-based counter-terrorism expert who does not wish to be named is that Pakistan has not yet defeated the threat of IS because of the "lethargic, laissez-faire style of governance of the current regime, as well of the previous set-up. It’s not only the IS and militancy; whether it is local governments, health, education or even picking up garbage from urban centres, governance is not the strong point of the federal or provincial governments."