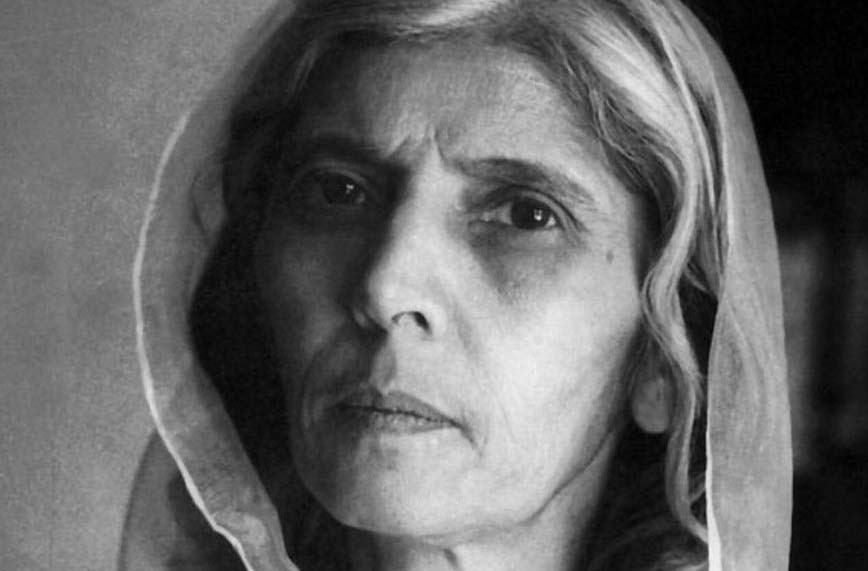

A strong personality with deep convictions, Fatima Jinnah’s life and work merit deeper and more critical study

July has been a very happening month. Not only has the United Kingdom witnessed its second woman prime minister take office in July, the month also marked the moment when Senator Bernie Sanders publically backed Senator Hilary Clinton in the presidential campaign.

If all goes well, by January 2017, the US, UK and Germany -- three of the world’s largest economies, will have women at their helm. They, together with the chairperson of the US Federal Reserve and the Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, will make five women one of the most powerful people in the world. This indeed is a great achievement, and something unthinkable even half a century ago!

July is a month also critically linked to a certain important woman in the history of Pakistan -- Fatima Jinnah. She was born on July 31, 1893, and she died on July 9, 1967, after a rather remarkable life. Even though she remained very much under the shadow of her illustrious brother -- Mohammad Ali Jinnah, she was also a leader in her own right and made a mark. It is a pity that her legacy has been largely forgotten in Pakistan, and only mentioned when linked with her brother.

The disinterest in her life is clearly shown in that even after nearly fifty years after her death there is not a single decent biography of hers, nor is there any deep appreciation of her role in strengthening democracy in Pakistan by standing up to Ayub Khan in 1965 -- then the apple of almost everyone’s eye -- and showing to the country that democratic values were more important that piecemeal economic development and gain.

Recently, I have begun reading the Fatima Jinnah papers and have been repeatedly struck by her sense of independence and forthrightness. She was never known to mince her words -- much to the chagrin of the first Prime Minister of Pakistan, Liaquat Ali Khan, and nor was she worried about what others might think of her. After the death of Jinnah, she faded away from the limelight but steadfastly issued statements on independence day and made a public broadcast on Jinnah’s death anniversaries.

In one of her broadcasts, on Jinnah’s death anniversary in 1951, she clearly showed her mettle. Apparently the government was concerned that she might criticise some of their policies and did not want her to read certain parts of her speech. Fatima Jinnah noted in her letter to the Controller of Broadcasting, Z.A. Bokahri: "On 11th September you sent for a copy of my broadcast at 7pm and you came at 8pm to my residence visibly moved by deep anxiety and entreated with tears to delete certain passages of my speech."

Undeterred, Fatima Jinnah stuck to her guns and argued that she would rather not do the broadcast if "there was no freedom of expression in an independent democratic state." This was a very significant declaration, as even in the ‘difficult environment’, which the Radio Pakistan official pleaded, she stuck to her principles, and underscored the centrality of ‘freedom of expression’ in whatever the circumstances. At that time a number of questionable decisions were being made in Pakistan with the blame being saddled on ‘conditions’, and so the stance of Fatima Jinnah against expediency was critical.

The text which Mr Bokhari wanted deleted had to do with how quickly Pakistan was forgetting the principles upon which the Quaid-e-Azam had founded Pakistan. In almost all of her speeches Fatima Jinnah was mindful of reminding people of the aims of the Quaid in establishing Pakistan and she always exhorted people to keep them paramount.

In her broadcast, she noted that the Quaid’s memory was not dependent on ‘structural monuments’. She stated that the devotion of the people of Pakistan was not ‘motivated by any idea of preserving and protecting their ribbons but springs up out of utmost sincerely and devotion.’ This was certainly a damning reference to the lip service the government of the day was giving to the Quaid’s ideals, and reflected a stark reality that this was being done even during the premiership of Quaid’s chosen lieutenant, Liaquat Ali Khan.

In her speech, Fatima Jinnah also lamented the stalemate in the Kashmir dispute. She had always referred to how close the Kashmir issue was to her and the Quaid’s heart, and she expressed her frustration that the dispute was lingering on much to the suffering of the Kashmiri people. She said: "We feel most vividly the lack of that giant master-stroke to which we were accustomed for the last one decade during our struggle for Pakistan…That sagacity and vision has now given place to drift." There was certainly some nostalgia here for her brother, but also sadness at the lack of initiative on part of the Liaquat government to achieve a solution.

By 1951, the negotiations between India and Pakistan had deadlocked and the UN mission was not going far either, and so there was some real frustration on part of Fatima Jinnah on this count.

Fatima Jinnah also spoke about the plight of the millions of refugees who were still living in squalor and disease in numerous refugee camps throughout the country. She emphasised that "the plight of millions of people who gave up their last earthly belonging in order to preserve and protect Pakistan are today in a most miserable plight. No doubt it is a gigantic problem, but it should not be forgotten that it is a human problem, and we cannot allow the vast mass of humanity to remain in an adulterated misery for a long length of time."

The disdain with which the provincial and central governments were treating the refugee issue was certainly causing her anguish and she was severely critical of how the government seemed nonchalant about their rehabilitation and in fact was quite content with the teeming millions of refugees living in miserable conditions in camps.

She reiterated the purpose for the creation of Pakistan and was dismayed that the government did not seem concerned to improve the lot of the people, their basic responsibility. She noted: "Freedom must be a reality for every individual and he should be able to live in an atmosphere where he can enjoy a peaceful and independent life." Again remembering her late brother, she stated: "He never submitted to falsehood. He never waited for others to take decision on matters affecting the welfare of the country." Here again was a damning indictment of the then government and the way in which the country was being run.

Fatima Jinnah, while not in active politics, was aware of the direction the country was taking and was adamant not to let the work and vision of her brother go to waste.

However, given the nature of her speech, the government was determined to blot out criticism of any sort. When it was broadcast to the nation there were interruptions at exactly the moments of criticism. Displaying her sense of humour, but also her keen eye for detail, she wrote to the Controller of Broadcasting: "It was only on my return home that I learnt of the interruptions in my speech and to my surprise the interruptions synchronised with the passages you pleaded for omission." Mr Bokhari did try to explain to her that "our generators went out of commission last Saturday and every effort was made by us to give full power to our transmitters yesterday during the national hook-up…I very much regret that we were not wholly successful in putting the transmitters to their full power with the result that some interruptions were noticed by out listeners…"

The Mother of the Nation was not amused and chided that "You seem to possess a very efficient and obliging set of transmitters ready to fail at your convenience…Your explanation is neither satisfactory nor convincing. Apology in such a case is only a meek expression of confession."

This one incident not only shows us the mettle of Fatima Jinnah but also the principles she held dear -- where freedom of expression was paramount. It throws open questions as to how important issues like the Kashmir dispute and refugees were being dealt with by the government. It also shows how governance in Pakistan was already being compromised just four years after its existence and within the first government of Liaquat Ali Khan.

Fatima Jinnah was certainly a strong personality with deep convictions, and her life and work surely merits deeper and more critical study.