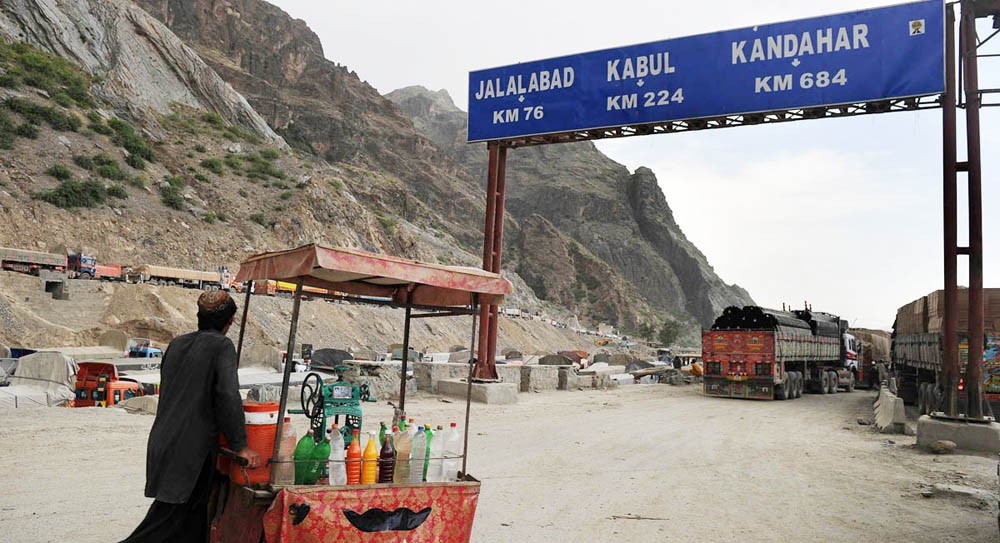

Pakistan’s military objectives for peace in the region could not be materialised without an articulate system on its long border with Afghanistan

The recent skirmishes between Pakistan and Afghanistan on Torkham border took place at a time when the Pakistani civil and military establishments reportedly claimed clearing considerable parts of the tribal areas from militants. Leadership in Pakistan views that after dismantling militants’ hideouts, a proper border management mechanism should be developed on Durand Line through mutual coordination.

Military objectives in Pakistan could not be materialised without an articulate system on its long border with Afghanistan. The way the people of both the countries exchange their views on the social media is shocking. An old debate on the Durand Line issue has resurfaced, showing a deep mistrust between the two neighbouring countries.

Durand Line was demarcated in 1893 as a result of an agreement between the British Indian government and Amir Abdur Rahman. The treaty was confirmed in 1905, 1919 and 1930 by the successive Afghan rulers. In the post-1947 period, a positive approach was exhibited by a number of Afghan leaders like Sardar Daud, Babrak Karmal, Norul Amin and Najibullah to solve the issue. But there is a section in Afghanistan that has always questioned the validity of the Durand Line. A perception prevails that it was due to the use of force that the Afghan Amir signed the Durand Line agreement. It is important to grasp the real situation at the time of the agreement.

In 1884, Russia captured Merv (a major oasis-city in Central Asia, on the historical Silk Road, located near today’s Mary in Turkmenistan) which brought the frontiers of Russia closer to Afghanistan and India. There was a desire shared by both Russia and British India to avoid direct clash which could result from even a slight advance by either power. It was deemed essential to keep their respective borders away from each other by keeping Afghanistan as buffer state. But Afghanistan could serve a buffer only if its frontiers with these two powers were clearly defined.

For this purpose, an Anglo-Russian Boundary Commission on the Russo-Afghan border started work in 1884. A final protocol was signed on July 22, 1887. It agreed on a border along the Amu River. In fact, in the delimitation of its frontier with Russia and Iran, Afghanistan was never consulted. The Afghan Amir was simply informed of all the decisions agreed upon by the commission regarding its borders delimitation.

The settlement of the Russo-Afghan and Iran-Afghan boundaries paved the way for the settlement of the frontiers between British India and Afghanistan also. Amir Abdur Rahman himself took the initiative and wrote to Lord Dufferin to send some officials to Kabul to point out the limits of the frontiers in cooperation with the Afghan officials. The British authorities were ready for the border settlement. Meanwhile, the illness of the Amir and rebellion by Muhammad Ishaq in Afghanistan delayed the sending of the mission for some time.

The Afghan Amir again wrote to the Viceroy that a mission be sent to Kabul. Viceroy Lord Lansdowne appointed Sir F. Robert, the commander-in-chief of the forces of India, to lead the British mission to Kabul for discussing the frontier issue. The Afghans’ perception that the Amir was not ready to fix border and that he used delaying tactics is unfounded. The real reason for the postponement was the appointment of Sir F. Robert, who led the British force in the second Afghan war of 1878-79.

The Amir wanted to settle this important issue of the delimitation of the frontier with a civilian officer or a statesman, and not with a soldier like Robert who was the champion of the British forward policy. Then they sent another mission under Sir Mortimer Durand for the settlement of this issue. Sir Mortimer Durand went to Kabul unarmed so as to remove the impression of the use of force or blackmailing altogether.

The whole arrangements were formalised in an agreement which was signed on November 12, 1893 by Amir Abdur Rahman and Mortimer Durand. There is no mention of any time-frame of hundred years in the original agreement and it is indeed a baseless assertion. It was absolutely an agreement concluded according to the norms of give and take.

Another important aspect of the agreement is the settlement of border in the hilly tracts. The settled districts including Peshawar valley, Bannu, Dera Ismail Khan have already been captured by the Sikhs under Ranjit Singh. The British government occupied these areas from Sikhs, not from the Afghans.

The next day the Amir received the British mission in a formal Darbar in the presence of the members of Loya Jirga, important civil and military officers and tribal chiefs. Interestingly, in his speech he pointed out that the interests of Afghanistan and Britain were identical and that the British had no evil designs against Afghanistan. In this way he democratised the contents of agreement from the Afghan public representatives. He exhorted them to always remain friendly to the British.

It was for the first time that Afghanistan had a definite frontier which would prevent future misunderstandings and would render Afghanistan strong and powerful after it had been consolidated with aid in arms and ammunition from the British. If it was a matter of pressure or force, the question arises that why the Amir accepted subsidy, annual grants and military assistance from the British? In fact, his vision was much progressive and he wanted to make Afghanistan a great state. He was clear that without definite borders it would be unrealistic to think of reforming the Afghan society.

In a nutshell, the 1893 Durand agreement legalised, formalised and institutionalised the arrangement that was already accepted by the Afghans according to the 1855 treaty with the British. UNO, Pakistan and the international community have genuinely never accepted this stand of Afghanistan. Playing politics on the border is contrary to legal norms and practices among nations.

Both states need to adopt a realistic and good neighbourly attitude towards each others. It would benefit the people on both sides in achieving long-term peace and stability in the region. Afghanistan and its people need to bring a positive change in their attitude and accept the Durand Line as the international boundary between the two states.

In the present scenario mutual trust and respect for each other’s sovereignty is much needed. Whenever, any hope for peace and development emerges in this volatile region, our moral obligation should be to support it wholeheartedly. Confusing and emotional statements from both sides of the frontier undermine all the efforts for peace. Afghanistan and Pakistan should recognise and defeat those elements that are bent upon keeping the region unstable.