Liberating themselves from tradition, artists are emerging as independent, avant-garde entities, defying established notions of aesthetics

There is a problem with the word ‘originality’. What it signifies is refuted in the very construction of the term. Normally originality means "the ability to think independently and creatively" or "the quality of being novel or unusual". Contrary to these dictionary meanings, the word ‘originality’ encompasses the word ‘origin’ which connotes a connection with some source or entity.

Nowhere else is the idea of originality as disputed as in the world of art. Practitioners, critics and viewers have multiple, often contradictory, definitions for it. What we understand today as originality is the notion that encompasses innovation as well as authenticity. Both artists and their collectors are bent on making ‘new’ works that are not only different from their previous creations but must be distinct from anything else produced before. The surge for uniqueness in art compels a number of artists to showcase completely different works since that’s the demand of the market.

New rests on originality, because only something that is original can be safely presented as unprecedented. Originality is sought in ideas, imagery, usage of material, and sometimes in the choice of material. However, the concern for originality is not solely the preserve of visual arts; it affects other creative fields too. It would be interesting to know that the term charba, frequently employed for films that are not original, has its origins in the practice of Indian miniature painting. Artists in the Mughal ateliers made initial drawings on animal fat (charbi) and, using it as a tracing sheet, transferred the sketch on wasli paper to paint.

But in the Mughal period, there was no notion of or insistence on originality. Artists learned to draw by copying other works, and followed earlier examples while making their own compositions. In fact, this tradition of following existing artworks was an important factor in inculcating new elements in the art of miniature. For instance, when Jesuit fathers and European envoys brought a few Western paintings to the Mughal courts, the local painters prepared copies of such high quality that, according to Abul Fazl, the chronicler of Emperor Akbar, the outsiders were unable to differentiate between the actual and the reproduction.

Read also: Adapting to the script

This practice contributed towards enriching the art of miniature, because, if one looks at the paintings of Emperor Jahangir’s time, one finds figures, symbols and part of landscape derived from Western imagery. What took place in the Mughal epoch was not a unique phenomenon because, in most traditional societies, artists were recreating works of earlier generations. Many artworks made in the medieval and Renaissance periods are reminiscent of other works because the worth of an artist lay not in the ability to ‘invent’ but to ‘excel’; thus each artist was working on examples from the past.

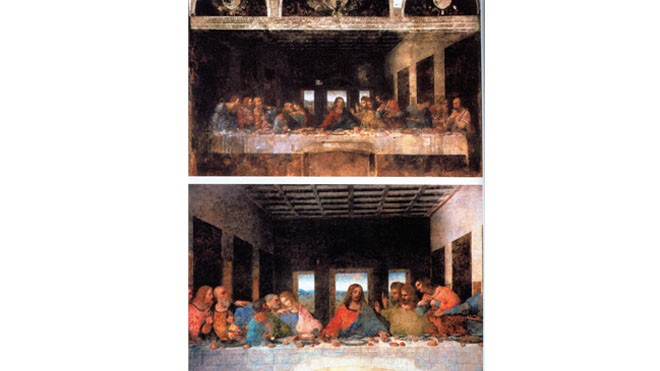

The theme of ‘The Last Supper’, painted by Leonardo da Vinci on a church wall in Milan, was not drawn from his own imagination since there were several paintings around the same subject. Da Vinci did describe an episode from history from some 1500 years ago but conveyed other ideas through that already known story.

According to Henry Geldzahler, the American art critic and curator, art is ‘making it new’. Something is already there and the artist transforms it so it appears new; because there is hardly anything that can be classified as truly original, lacking all links whatsoever. Even if we do not subscribe to Plato’s Cave, we who take pride in and strive for originality are devoid of it.

Yet, we often come across this notion because, with the age of modernism, artists have liberated themselves from tradition. They have emerged as independent entities not in harmony with society but ahead of it (avant-garde) or in defiance of established and admired notions of aesthetics. What they aim to create is not some sort of convention but a unique voice, which identifies them as independent human beings. This has led to the idea of authenticity as well. The artist, free from the shackles of tradition, can now produce something that does not represent the past or people. Instead he is the sole maker of ideas and images.

Hence the signature style of an artist has come into focus, particularly after the canvases of Vincent van Gogh, characterised by his handwriting-like brush strokes and the story of the artist as a tormented soul. Each work was expected to be executed by the artist.

This is a recent phenomenon- when we admire the work of Leonardo da Vinci, we know the authorship of da Vinci, but we are also aware of his pupils who worked on the surface with/for him. Likewise, when we look at the works of several other artists we are conscious of the fact that a Rubens is not by Rubens purely but the Flemish painter only put the final touches to a composition prepared by his apprentices (hence the term master strokes).

In a strange way, the 21st century has returned to the past because in this digital world it is impossible to insist on originality or authenticity. With just a click, one can trace the links of an artist’s thoughts, concepts, and technique to someone living in a faraway land. By relying on computers and technology, it is not possible to locate the ‘hand’ of an artist. Replicating the Renaissance time, artists today are also using other humans and machines to create works that are associated with their name.

In a world where boundaries of all sorts are blending, the notion of originality is becoming out-dated too.