In her recently concluded solo exhibition at Sanat Gallery, Karachi, Kiran Saleem deals with the past on multiple levels

The work of Kiran Saleem reminds one of Jorge Luis Borges in more than one sense. The Argentine author produced fiction with introductory notes about the text being a transcription or translation of someone’s work from another time and region. In the beginning of his career, this declaration was considered true till it was realised the writer was commenting upon a world in which ideas of authorship, originality, influence, inspiration and imitation needed to be redefined, rather redrawn.

Going by Borges’ example, everything has already happened and we are only repeating the past forms. Yet this repetition is a voice with unique sounds and strands. Because whatever is recreated ceases to be a copy; it becomes a work of originality. Just as fables, anecdotes and incidents are recalled in daily conversation to comment upon contemporary situations, the same thing happens in the realm of art and literature. Thus, in the fiction of Intizar Husain, episodes of Buddha’s previous lives (from Jataka tales), accounts of Hindu mythology and stories from spiritual books are re-narrated in such a scheme that it is difficult to determine the nature of text belonging to a past source or from present times. Only a further reading makes one aware of how the master craftsman of Urdu literature weaves a narrative that invokes the past but portrays our epoch.

With a similar sensibility, Kiran Saleem deals with the past on multiple levels. In her recently concluded solo exhibition (May 24- 31, 2016) To See, or Not to See at Sanat Gallery, Karachi, she has created paintings with reference to past art works.

In her selection of images from European art history, one detects a specific frame of mind that is not about emulating older paintings but interpreting the act of art making. Through her incredible skill, Saleem convinces the viewers that they are looking not at a painting but a paper with printed picture of an artwork -- and the sheet with its white margins is attached to a blank surface. In most of her works, paintings or their sections are reproduced but appear as prints, sometimes crumpled or creased and taped on the surface of canvas.

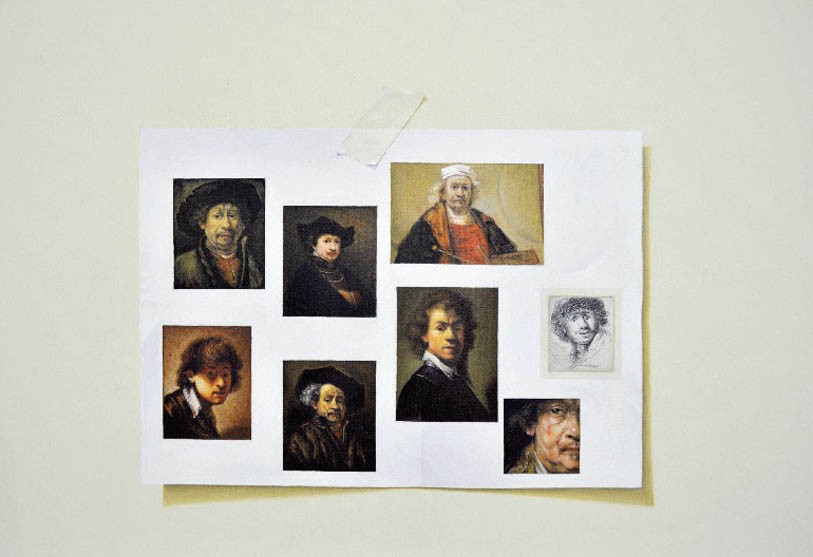

So no matter if it is the self-portrait of Rembrandt, Raphael, Gustave Courbet, Frida Kahlo or Jonathan Richardson; Water Lilies by Claude Monet; or the dual figures from The Betrothal of the Arnolfini by Jan van Eyck (in torn state), each is intricately replicated. Yet, one is conscious of how the artist is concentrating not on recreating the past paintings, but reflecting on the edifice of art history.

Saleem’s selection of self-portraits of artists from Renaissance and after unfolds the debate about authorship and authenticity. Self-portrait of an artist is a work that binds with their character, individuality and signature. They may be addressing other themes in common domain (like the original sin, the last supper and crucifixion etc.) in their personal style, but when it comes to rendering their face, they are revealing their identity.

Kiran Saleem has reconstructed a number of those self-portraits along with a work comprising a tiny piece of paper bearing the signature of Rembrandt (another form of self-portrait!). Her work becomes an inquiry into the notion of authorship; to replicate self-portrait and signature is an attempt to own the legacy of art but in a paradoxical way -- by acquiring what has been too personal and private for an artist.

On a closer look at her canvases, one feels that in her hand the art of past turns into a metaphor of our contemporary life. For instance, works with the images of human genitals, either from the painting of Adam and Eve by Cranach, or a canvas by Courbet (The Origin of the World), presented with camouflaged elements, suggest the way the concept of morality persists, yet changes according to the shift in cultural contexts.

Perhaps, Kiran Saleem’s aesthetics depends upon her act of reducing large works into small pieces. Monet’s huge Water Lilies is represented by a segment of it painted on a small scale next to the original source on a paper attached to canvas (the successful illusion of reference material joined with a tape is painted by her).

In another work, the artist has composed a section of eyes from Courbet’s self portrait, a portion of female breast in Lucian Freud’s work and a part of chest wound from Cranach’s painting about crucifixion. All these visuals are rendered like torn papers stuck to canvas with a strip of masking tape. One becomes conscious of the link between the three images, as each contains a circular form -- repeated in the eye, nipple and wound -- thus combining the apparatus as well as the objects of spectacle!

In fact, this act of appropriating past masters is not only a means of paying homage to great artists, it also signifies the divide between the mainstream and the periphery. In the art colleges outside of West, usually the canon of art history comes in the form of reproductions: painted like a copy, printed in an art book, or purchased as a poster on the roadside. So the first -- and lasting in most cases -- contact and experience with Art History is basically negotiating with replicas.

Her work in a sense alludes to the contemporary world of media which is manufactured with layers of facts gathered from diverse sources from all over the world in order to make a credible story. She reminds of the encounters of an art student from South Asia and several other parts of the world, who ‘imagines’ masterpieces, without having a chance to glimpse the actual canvases. For the student, real is the ‘reproduction’ printed in an art history book or available on a website. Saleem represents that version, and with all its creases, folds, smudges and marks affirms how art history, or art for that matter, is not a universal experience but a means of dominating the mainstream discourse.

However, in the age of mechanical reproduction and virtual literacy, the boundaries between real and replica are blurring. Everyone is familiar with Mona Lisa but how many have been to Louvre to look at the portrait by Leonardo da Vinci. Thus which is the real Mona Lisa -- a canvas of 30×21 inches hung inside a glass box in a Parisian museum or its countless prints sold in the streets all over the world? Saleem probes that aspect of our art and existence, in which the tension or comparison between different places does not exist. Because whatever is created in any part of the globe can be appropriated, assimilated, accumulated and adapted at other areas in no time.

A situation stated by Julian Barnes: "…that we all have a Mona Lisa, this would make Mona Lisa less valuable, less fetishised…..We could all have great paintings. And it would be democratic, wouldn’t it?"