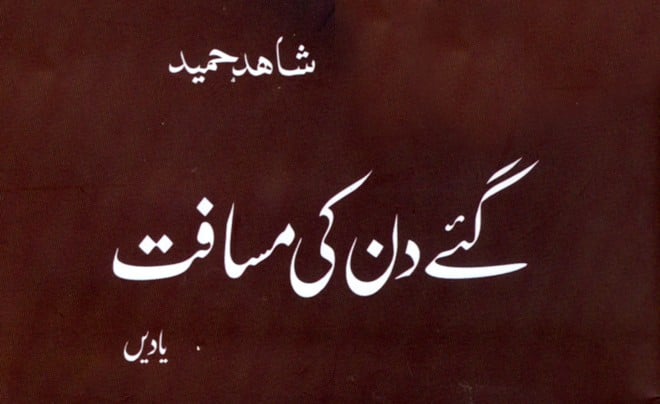

Shahid Hameed is arguably one of our best translators. He does not go for the minnows and would rather have a whole of a book to tackle. That is why he has translated Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Dostoevky’s Brothers Karamazov into Urdu. Truly big translations bolstered up with extensive annotation. Such derring-do would satisfy most men but not Shahid Hameed. He went on to translate Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, again well-annotated, and rounded off these gargantuan labours by compiling a massive English-Urdu dictionary. And now, as a farewell gesture, he has written an account of his early life spent in a village in what’s now the other side of the Punjab.

Somehow, idiosyncratically, this life story comes to an end in 1947, subliminally suggesting that the partitioning of India had sundered his life, splitting it into two irreconcilable portions. You cannot question a writer’s integrity or intent. It is well within his rights to reveal or conceal as much of his life as he wishes. But it leaves the readers baffled. What he has to say about the years preceding the partition is lively enough. So why can’t he describe graphically the early years he spent in Lahore after 1947?

It seems that we would have to make do with what is available.

Born in 1928, he was only nineteen when Punjab was partitioned. How could a bit naïve young man know about things that happened a long time ago, when the world around him had the look of a sequestered place and the events unfolded in a slow, placid manner? There won’t be a great deal to tell, you may surmise and, in general, would be in the right.

But Shahid Hameed has circumvented all this by following a pretty eccentric path. For want of a proper word I would coin a new, albeit an ungainly, one. What Shahid Hameed has written is an autobiogazettography. The book has as much to do with the events of his life as with his surroundings and history in general. The narrative does not travel in a straight line but veers this way and that at the drop of a hat. There are many parenthetic diversions and askew asides which beef up his account and turn out to be not boring or extraneous, but fairly diverting.

He was born in Purjian, a village in tehsil Nakodar. The village in the distant past was situated at another place. Then River Sutlej, in an unpredictable fashion, as rivers sometimes do, changed its course. The village vanished in the inundation and was later relocated at a higher ground. It is interesting to learn that Abdul Aziz Khalid, the well-known poet and linguist, was his class fellow in the village school. I can’t think of any other tiny village which may have produced two such eminent writers. Small places do occasionally hide big surprises.

Unlike West Punjab where landowners hold sway, there were no big landholdings in Jalandhar and this fact alone ensured, as Shahid Hameed points out, the emergence of a more or less egalitarian society, eschewing any sense of alienation. I doubt if a more detailed and convincing account of nearly all aspects of rural life, as it was in Jalandhar almost eight years ago, exists in Urdu. A lost world now, in the true sense of the word, peaceful, unhurried, free from pollution, violence and crime, content with the simplicity of things, of existence, without any outsize ambitions and almost stoical

His memory is to be envied. To recall, in such detail, the rituals of daily life, the passage of seasons, games that were played, the things that he saw being made, so many simple artifacts, the plain and nourishing food, the persons who mattered to him or to the village in those days, is nothing short of astonishing. How many among us can now describe, phase by phase, the digging and construction of wells, fast disappearing everywhere these days?

It seems true, as some writers have asserted, that it is only during our childhood and boyhood that the world seems a newly-minted source of unending wonder. Yet how few of us, at the fag-end of our life, remember with any degree of certitude, what it was like when we were very young? Some details do stand out but the rest is a gray area of make-believe and conjecture. His decision not to write about the time he spent in Lahore in the company of Nasir Kazimi, Intizar Husain, Muzaffar Ali Syed and Ahmad Mushtaq is, therefore, to be doubly regretted. What did they talk about or see in the course of their night long wanderings, alluded to in the book, would now, alas, remain a closed chapter.

There is a streak of intransigence in Shahid Hameed’s temperament. Therefore it came as no surprise when I read in his book that, after being reprimanded rather strongly by his father concerning a matter in which he was not at fault, he decided to run away from home for good. But his determination soon wavered, and when he boarded a train bound for Delhi he knew that he only wished to show a bit of pluck. His elder brother was living in Delhi and the fugitive managed to find him. How he would have fared had his brother been away from Delhi is best left to the imagination. Could have begged his way back home maybe. Or we won’t be reading these memoirs now, an interesting possibility.

The diversions are many and their relevance varies. We learn how difficult it was to obtain a passport in British India, how effective were the postal services, nowadays in a shambles, we read about the Simon Commission, the 1936-37 elections, Miss Mayo’s infamous book, Mother India, which was not all bunk by the way, the rise of Hitler, some highlights of British history and glimpses of Lahore as it was in 1946-47.

In the end, Shahid Hameed expresses a sentiment which many of us would share. He first quotes Ghalib who refers to Delhi after it had fallen to the British army in 1857. "Suddenly the times changed and the persons I knew were no more. The circumstances differed, the sense of camaraderie was lost and gone was the cheerfulness." To this Shahid Hameed adds dejectedly "The same thing happened to me, to the place I belonged, the people who lived there. The place was ravaged and is now occupied by strangers."

It is a shame really that the beginning of our independence should have coincided with such savagery. To do things in a hurry is a devilish business.

(Gaye Din ki Musafat has been published by Ilqa Publication, Lahore)