Najm Hosain Syed’s detailed essay on the Punjabi version of Dastan-e Amir Hamza tries to see things in their historical and anthropological perspective

The single-volume Dastan-e Amir Hamza by Ghalib Lakhnavi was first published in 1855 and the author, for reasons of modesty or its opposite, just following the custom, preferred to call it a ‘translation from Persian’. This Urdu text was never reissued but in 1871 Naval Kishore Press, Lucknow, hired the services of Abdullah Bilgrami to prepare a version of Dastan-e Amir Hamza. He used Ghalib Lakhnavi’s book as the source text and reworked it by adding ornate passages and poetry to it.

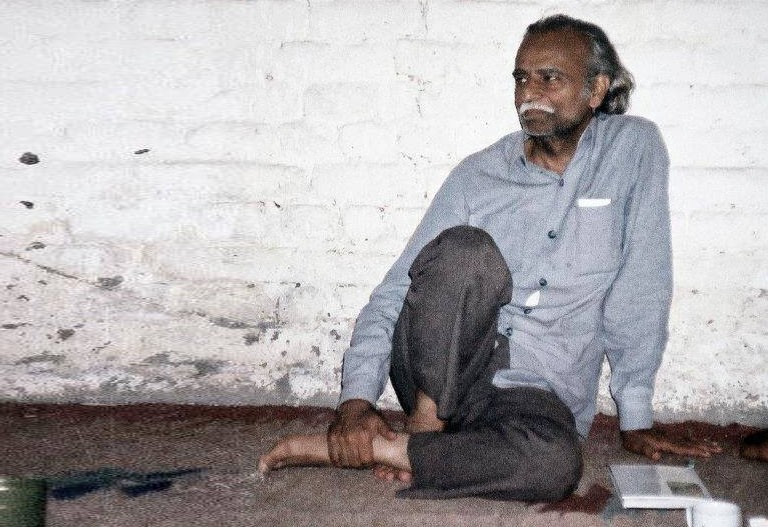

Ghalib Lakhnavi’s original version may have been the source of the Punjabi verse version of the Dastan penned by the young poet from Hoshiarpur, Maulvi Ghulam Rasool (1849-1892). As Najm Hosain Syed -- the most notable figure in contemporary Punjabi literature on this side of the border -- says in his enlightening essay on Maulvi Ghulam Rasool’s feat, Maulvi Sahib wrote obsessively and finished the several thousand couplets long Punjabi version in a matter of four months, beginning some time in 1869 when he had been a traditionally educated young man from a small zamindar family.

Najm Hosain Syed’s detailed essay "Qissa Reet Kureet" included in a collection of his critical writings called Aahian vichon Nahian presents a revealing analysis of the book and the process by which it was sold in the print edition -- that came out in 1920s or 30s, i.e. about half a century after the poem was composed -- to the new readership created as a result of the first-ever public education system in the subcontinent.

Unlike the usual fare of Urdu criticism of the classical Dastan fiction, Syed’s analysis tries to see things in their historical and anthropological perspective. By the time the edition which Syed studies was first published, northern part of the subcontinent, especially the Punjab, had undergone a plethora of socio-economic changes of deep and vast political consequences.

The modern system of public education, introduced by Christian missionaries and the British colonial administration, had started functioning around the time Ghulam Rasool -- born in 1849, the year of annexation of Punjab by the British East India Company -- finished his traditional education in Persian and Arabic. In the changed times, he started teaching Persian in one such modern school near his village.

The process of replacing Persian as the language of learning and administration by English at the higher levels and by a local language at the level of lower administration, the thana, the kutchery, and the primary and secondary schools had begun in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The predominantly Muslim elite in the Punjab, who had reasons to resent the long and harsh rule of Ranjit Singh’s Takht Lahore, sought to identify themselves culturally and politically with the former nobility of the areas around Delhi by opting for Urdu instead of Punjabi which was written in the Gurmukhi script and was closely identified with the Sikh community. The attitude of looking down upon their own language -- especially in its written form -- seems quite common to this day among Punjabis -- a possible reason why Syed’s analysis of the Dastan fiction remains unread even among the scholars in this specific field (many of them Punjabis), as he made it a point to write it in Punjabi.

Read also: Hamza’s stories

More importantly, by the time this edition of Maulvi Ghulam Rasool’s long Punjabi poem, Dastan-e Amir Hamza, was published in its new, printed version, much of the canal network covering the northern and central Punjab had been constructed and made functional, with its attendant social engineering of settling in and giving newly-created farmland to the ‘agricultural castes’ like Jats and Arains. In fact, the book had been published keeping the prospective buyers in mind who had obtained modern education (in Urdu) and joined the new professions that the socio-economic changes under the colonial system had brought into being.

Come to think of it, the decision of the colonial administration -- made in view of the Cotton Hunger as a result of the American Civil War of 1860s -- to turn vast plains of Punjab into a source of raw material for the cotton mills in England has shaped the economy, culture and politics of the area to such an extent that we, the citizens of the present-day Pakistan, can be considered products -- in terms of demography, economy and culture -- of the canal system of Punjab.

Syed begins his essay by reproducing the interesting Urdu texts preceding the printed version of Ghulam Rasool’s Punjabi verse version of the tale of conquests by the semi-imaginary ‘Muslim’ warrior:

On the next page there is an ad for another, seemingly related publication:

Syed then begins his commentary on the publication by deconstructing the texts reproduced above. Before we discover in detail the features of his analysis of the long poem itself, the following is what Syed has to say as opening remarks (in my imperfect translation:

******

"There are a number of things to be asked and told about the effort to promote this book. Such as, who are these "Sahiban shoqeen nazm Punjabi" that are being given this good news? Apparently, they are connoisseurs of Punjabi poetry, but the language through which the book is being shown and sold to them is the durbari Urdu. Are these shoqeen people akin to those apprentices of Maulvi Sahib on whose request the book had been written? The residents of Alampur Kotla, the village situated in an island of the River Bias, like Ahmad Yar and Samand Khan, sons of small-time farmers like Maulvi Sahib himself, progeny of the kammi-kasbis like Jani Mochi and Noor Kasai? If the petty farmers and rustic kammi-kameras were the one who had a taste for Punjabi poetry, wouldn’t it have been more effective if this advert for the Punjabi book was in their own boli?

"However, they are precisely the people this advert is not meant for. It is meant for alims, the intelligent people coming from the leading mail [caste-class group], students, teachers, munshis, government servants and businessmen.

Read also: The amir and the alim

"The book was first published in the 1920s or 1930s, or maybe even earlier than that. In that era the safed-posh alims, intellectuals, students and such like were already enchanted by the Urdu and Persian poetry; where were the "shoqeen nazm Punjabi" left among that lot, and, indeed, why? Besides, were they generally in the habit of liking Punjabi poetry or this particular creation by Maulvi Ghulam Rasool had some special masala to glue them to it? If Maulvi Sahib’s writing had been read in the context of his times, we would have been able to get to the bottom of these things. But some insight can still be gained by looking closely at the word "Sahiban". "Sahib" in the old days was the term used for addressing important personages holding large properties and high places in society. When the Angrez came, they monopolised this title for themselves. So the real "Sahib" was either the Gora ruler or those desis who were given a kursi [an important position] by him. It matters little if the advert employs the word in its old sense; the readers in the colonial times were able to get a kick of the new Sahib-ness out of it nevertheless. Not just this word, the whole advertisement is an effort to lure its readers by affording them an amalgamated whiff of the old and new respectabilities.

"With a broad brush "Khalq-e Khuda" has been daubed into the "Public", to attain a certain status under the ruling gaze. The advertisement plays a delusionary trick with the customers to sell the book; so it is befitting to play with it a little and call its bluff.

"The word "shoqeen" and its plural "shaeqeen" are respectable terms in the durbari language. However, the lok boli can sometimes invert the entrenched respectabilities to make them look their opposite. In that street tongue of the commoners, therefore, "shoqeeni" means to imitate the wealthy and affluent, to behave as they do to impress people around, to pick up the leftovers of the high fashions and lifestyles.

"The booksellers of the first quarter of the twentieth century were still donning the old garb of "Tajiran-e kutub" but on top of that have also worn the new suit-boot of "…& sons". Those who have been educated in the previous half century or a little more under the British Raj have acquired the fresh taste of the new shoqeenis but at the same time they are busy trying to make the old ones new. Does this whole thing have a secret common with the writing of Maulvi Ghulam Rasool? This question does merit a place among things that ought to be asked and addressed about the book.

"Men of the Bazar distribute their objects by presenting them as things used by important persons belonging to dominant social groups, while at the same time deluding the socially weak ones -- their customers -- that these objects can, if they buy them, transport them to the world of the high-ups. The beauty, the power, the courage that you observe among the upper class people is in fact the magic worked by these very objects. Be our customer and become a resident of this jadoo-nagri. All this business of selling and buying takes place through a different, new usage of language which, prior even to the transaction, transforms not just the object but the one selling it, using a magical make-up, and brings both right in front of the prospective buyer.

"This clever usage of language hides the real essence of the objects, their real existence, their real relationship with the man using them. It does not employ the common meanings the words hold, but the intimacy that the words enjoy with the lifestyle of the ruling classes; the glitter of glory and the awe of power that the antics of ruling have touched the words with, changing their sounds and shapes. The language of the advert for Maulvi Ghulam Rasool’s book is the same magical language. It resembles the nine-hundred-year-long reign of the Turk, the Mughal and the Englishman. The newly invented needs of the ruling classes are being used specifically for these new purposes, and they in turn reinvent their magical power. This upper class magic of language seeps into the lower class creatures and gives them a new way of contemplating their being and action. The language may bear any name; as long as it works the magic of the upper class gaze it ceases to be a language and turns itself into a tool of power in the hands of those wielding it.

"Not just the advert but the whole process of selling it imbues the object being sold -- the book -- with the magic of high living. The mention of its registration is not just to warn the competitors in the business of publishing but also to reassure the reader of the book having earned the approval of the Sarkar. The proper registration and the condition of the publisher’s signature give a respectability to the book born out of an official SOP. Also, the buyer is being informed that the asli product that is being sold to him is being jealously eyed by a number of counterfeiters.

"The customer has great ambivalence regarding the language of the book. When those coming from down below attain, through new education under the colonial arrangement, a somewhat respectable station in life, they start considering their own language a sign of their low, backward origin. The new education is in fact the teaching of the new language, which is the new way of living and of being. By taking this shower they need to wash away the marks that their low birth has branded them with. The advert tells the reader that even though the book is in his old language, and he is justified to have his apprehensions, now there is nothing to worry about, as after having been imbued with the whiff of the new it is no more the same old language in which he has grown up.

"Even the Maulvi Sahib is less the author of the book than a component of the exercise of selling; to be fair, the sellers consider themselves as such too. By using this magical language, they have transformed themselves, the book and the customer into upper class, respectable things; this has been done with the author as well. From Ghulam Rasool he has been recycled into Maulana Maulvi Fazil-e Ajal Akmal Ghulam Rasool Sahib Marhoom, resident of Alampur Kotla, tehsil Dasoha, district Hoshiarpur. This fully decorated name, accompanied by full address, serves the same purpose as that asli signatures of the publisher. The new name and the geographical station of the author testify to a newly born lack of trust dogging the customer and seller alike. What is this mistrust and how is it related to the writing of this book and the tale of Amir Hamza?

"When a culture is established on the very foundation of division between the powerful and the powerless, what can it produce except mistrust? Not trusting the other leads to a lack of trust in oneself, a deep, many-faceted distrust about one’s very existence. The sense of menace and concern that this lack of trust generates, awaken a perpetual need in a person to move forward on the path of social achievement; to earn more and consume more. He feels this is the only way out for him, but this way out worsens his ailment. The gulf between the powerful and the weak ever keeps on widening and the sense of distrust deepening."

*****

This is how Syed sets the stage for his singular analysis of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza in the Punjabi verse version which it would, in my view, be quite illuminating for us to read critically.

This is the first part of a fortnightly series on the subject which will appear on the literai page of TNS.