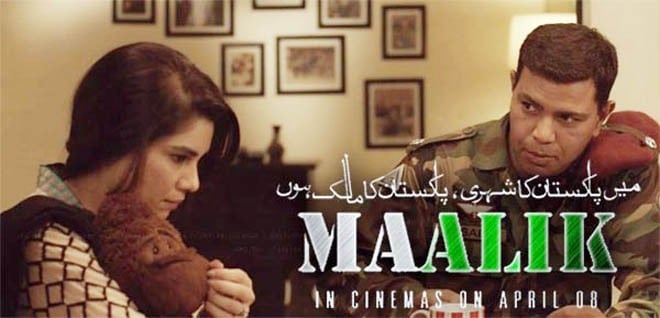

The only reason I sat through Maalik was because of memories of the PTV drama serial Dhuwaan. For school kids like me growing up in the 1980s and ‘90s, Dhuwaan was fantastic television -- and Ashir Azeem knew how to bring together action, suspense and good humour. So when I read news of Maalik being released I knew that I wanted to watch it asap.

What followed was largely disappointment -- and now controversy. Maalik’s certification for public exhibition as a film has been effectively cancelled under the Motion Pictures Ordinance 1979 ("the Ordinance"). Technically the certification that was in field is not in existence any more. However, this is being termed as a ban -- because that is what it effectively is, i.e. without a certificate from Central Board of Film Censors (CBFC), a film cannot be exhibited publicly.

This was not a situation where a party applied for a license or certificate and the relevant authority decided not to issue it. Had it been such a case the burden on the government authorities would have been far less than it currently is; power to grant or deny a license confers vast discretion in the granting authority. It undertakes a review of the relevant application and its decision carries high value, akin to that of an expert’s opinion. Courts, in constitutional jurisdiction, generally respect such decisions of expert bodies or sector-specific regulators. They do not second guess expert bodies’ decisions (or factors that weighed with experts/regulators) nor are they keen to sit in judgment over the evidence on the basis of which a decision was made. All that they care about is the process.

However Maalik is a step beyond this. By granting the certificate for exhibition the expert (CBFC) made it clear that Maalik qualified under the relevant criteria. Now the federal government, a powerful actor, is exercising its "revisional powers" under section 9 of the Ordinance to effectively cancel that clearance. What changed since the first decision granting clearance?

The relevant notification, as reported in the papers, is surprisingly silent on this issue. The federal government does have the power under section 9 of the Ordinance to look into matters regarding a film which has been granted a certificate or which is pending clearance. It must, however, conduct an inquiry in such a situation to ascertain the relevant facts -- although it does not need to provide the affected party a notice of its intended action.

If it disagrees with the clearance certificate granted by CBFC the federal government does have the power to direct that a film, which has received a clearance certificate from CBFC, shall be "deemed" to be an uncertified film. This is a drastic power and has worried, for a while, those with an interest in constitutional law and free speech.

However the discretion of the federal government to exercise this power is limited by the Ordinance. Consider the proviso to section 9 which provides an exhaustive list of factors which must back up a decision of the federal government: the government must be satisfied that it is necessary to deem a film uncertified in the interest of the glory of Islam or the integrity, security or defence of Pakistan or any part thereof, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality, or to prevent the commission of, or incitement to, an offence. (Paraphrased for the ease of readers, this is not a verbatim reproduction of the language of the statute).

Which of these rather broad grounds form(s) the basis of the notification issued by the federal government?

Ashir Azeem’s lawyers will, I am sure, challenge this in court. Equally open to a strong constitutional challenge is section 9 itself of the Ordinance -- where the federal government is not required to notify a party of its intended adverse action, not even before effectively cancelling a license.

However apart from the legal issues there is a broader aspect here that relates to free speech. Yes, Maalik as a film is not great. And its depiction of Sindhi politicians as corrupt with generals and Punjabi servants of the state being saviours is problematic -- it arguably reeks of ethnic prejudice.

Particularly shocking to me (spoiler alert!) was a moment in the film when a private security guard shoots dead a chief minister because the CM would never get convicted for his corruption and sexual offences otherwise. For a second I could not believe it that a film was showing in a positive light a killing of a state functionary by a man hired to protect him. The Qadri issue, of course, is fresh in our memory.

But then I had to remind myself that, regardless of my opinion, this is a film. And like any work of art it has certain leanings.

Furthermore, glorification of vigilante violence, torture or actions outside the law is not new to cinema or modern day entertainment. From James Bond to superheroes to 24, we have seen it regularly. Indeed, Dhuwaan glorified such actions too -- for the greater good when law was an inconvenience.

Should Ashir Azeem be expected to hold his project hostage to Qadri’s actions? Maybe it was irresponsible to script it like this but it is his film. The fact that the audience in a Lahore theatre, where I watched the film, loudly applauded the killing scene I just mentioned made me cringe more -- however it also reminded me that the problem is not the film but the attitude. This film is not responsible for people celebrating extra judicial or "heroic" murders for the greater good. The root causes for that lie elsewhere and what have we done to address those issues?

Banning Maalik is a terrible decision. Freedom of speech exists to protect speech that is often distasteful, irresponsible or downright repulsive. Whoever decided to ban the film has done the federal government no favours -- since the film will now be talked about even more, with the added allegation that politicians have banned a film that discusses corruption by politicians and makes the military look good.

The fact that the federal government chose not to disclose any reasons in the public sphere, at the time of cancellation of certificate of exhibition, will make it extra hard for the government to come out looking unscathed by this.

The fact that ISPR was one of the funders of the project is also causing a necessary debate. However taking money from ISPR does not extinguish Ashir Azeem’s rights as a filmmaker to have his film exhibited and his/his colleagues’ speech (exhibited in script and film production) protected.

We all know that free speech laws, like all other laws in this country, are applied selectively -- but this cannot be allowed to result in a situation where we celebrate an illegal process because it achieves an outcome favourable to your politics.