In Ghulam Mohammad’s solo show at Rohtas 2, one sees how the artist is exploring and investigating the role of language in so many different ways

I went to see Ghulam Mohammad’s exhibition on the morning of the day it was supposed to open officially. Observing his works on the wall, I spotted a low table with old newspapers. Ghulam Mohammad’s mixed media and the discarded daily newspapers were completely unrelated, yet had a connection.

Both contain letters: recognisable, readable, understandable but unbelievable. These are printed on the pages of newspapers, and cut, cropped and composed in a manner that makes them almost incomprehensible in the art of Ghulam Mohammad. The comparison between the usage and destiny of letters in the two entities is uncanny but it presents a clue to the essence of Ghulam Mohammad’s pictorial pursuits.

Since his graduation from BNU in 2013, Ghulam Mohammad has been employing a visual vocabulary about dissecting and deconstructing language. Carefully cut letters on a tiny scale are joined to create different forms and patterns. At some point, they lose their readability and can be enjoyed or discovered merely as shapes and textures. He has recently been shortlisted as one of the 11 artists for the coveted Jameel Prize 2016 -- an international award for contemporary art and design inspired by Islamic tradition.

The recognition of Mohammad in such a short period of time is impressive. His recent solo exhibition Chaan-Been (April 9-30, 2016) at the Rohtas 2 Gallery Lahore confirms the command of the artist on his craft, as he painstakingly separates each letter and then joins them in a different order. By and large, the scale of the letters is same and they belong to one language -- Urdu.

The presence of these tiny characters out of their original context and into a new formation is incredible, magical, since we know language only through its structure and content. Ghulam Mohammad aims to explore that aspect of language which deals with or reduces it from a system of sounds and thoughts to a collection of variable shapes which can be placed at random or according to an individual’s whims and wishes.

In reality, his act of cutting each letter and composing it in a new setting is not merely a formal formula but a far reaching exploration, even if the artist is still wondering about it. For instance, if a person wishes to express even the most outrageous, rebellious and subversive idea, he is forced to communicate it in a pre-existing syntax; hence the contradiction between the freedom of speech and the tyranny of speech.

One feels this link or constraint is crucial in the art of Ghulam Mohammad because he is negotiating with language not only as a means of expression but as an independent institution. In fact, his formal and technical method of making a language -- which is recognisable as Urdu but incomprehensible -- alludes to our present political discourse as well as to the nature of language.

In her essay ‘Power Politics’, Arundhati Roy reflects that as a writer "language is the skin on my thought", but observes how language becomes a tool to conceal reality and real meanings. A practice often witnessed in diplomatic or state briefings where words and expressions are used not to tell the truth but to camouflage it.

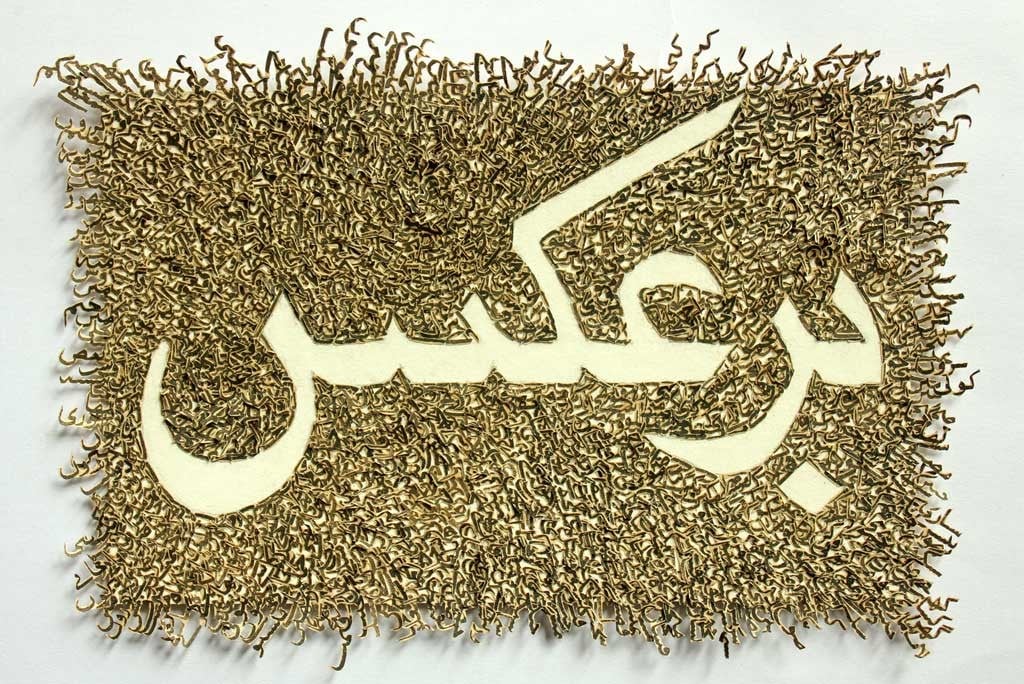

In Ghulam Mohammad’s works such as Bur-Aks (opposite) and Khaali (empty), one sees how the artist is exploring and investigating the role of language as a blinding power. The mixed media depicting the word Khaali, contains a web of small letters around the outline of this Urdu word that means absence. Similarly, Bur-Aks appearing as a white portion next to layers of letters signifies the other side of language that is often hidden from us. Jacques Derrida in one of his books explains that the way we speak reveals our decision to pick one word and discard all other synonyms.

It feels that Ghulam Mohammad focuses on the left-out segments of our discourse and tries to find new interpretations which in their course lead to parallel ideas. Here, one must not confuse his work with calligraphy, as he is using text beyond its readability or context. In some works, the meticulously-cut and combined letters appear no more than texture to create a tactile surface. In that regard, he seems to be following a certain tendency amongst artists: to find their voice at an early age.

The problem arises when that voice becomes a style or habit. An artist dealing with one issue is bound to rely on repetitive imagery in various pieces, thus leading to a dead end. One feels that Ghulam Mohammad might be facing the same situation, yet he is trying to investigate (the name of the exhibition means ‘investigation’) the structure of language, stressing its regional and cultural ties. Hence, one comes across works constructed like rug or carpet, with letters placed in the form of fringe outside the main format or rectangle.

However, these excursions in language or script appear more like stylistic investigations when compared with his other works which are sparse (and devoid of any other colour except black and white). The aspect of colour is important because language is usually perceived to be devoid of colour, thus books are printed in black ink. This implies that word or text does not require any other colour as it does not need any other connotation except its meaning.

In his surge towards stripping language from meaning -- since only letters survive but no words -- there is another work which is an exercise in shifting the existing content. In a tiny linear sequence on a large white paper, Mohammad has rewritten a text of Manto writing about his creative process, but switching the order of letters. Thus one finds it difficult to read till one realises the real concept of the work. Although the artist describes censorship as his idea, there may be another dimension -- the invalidity of handwritten language, especially in this age in which knowledge does not consist of words printed in ink on paper but in a small stick that opens up shelves and rows of libraries once it is connected to a computer.

Thus, the exhibition of Ghulam Mohammad, regardless of its theme or position, offers a chance to glance the last words before these are lost behind our glowing, glittering and glorious screens.